Protective Brain Molecule May Stave Off Alzheimer's

Scientists have long wondered why some people develop Alzheimer's disease while others have healthy brains throughout their lifetime. Now, new research identifies a molecule that protects brain cells from the stress of aging, which may stave off neurodegenerative diseases.

Researchers found that people who experience early cognitive decline appear to have lower levels of a stress-protecting protein in their brains compared with cognitively healthy people. The finding suggests a possible target for diagnosing or preventing Alzheimer's disease and other forms of dementia.

Scientists know very little about how the human brain responds to stress, said Dr. Bruce Yankner, a professor of genetics and neurology at Harvard Medical School and leader of the study, published today (March 19) in the journal Nature.

"This is the first study to explore that [response] in the aging human brain, in relation to Alzheimer's," Yankner told Live Science. [Living With Alzheimer's in the US (Infographic)]

Aging protection

As the brain ages, cells are exposed to stress and toxins, but some people's brains seem to be more resistant to these stresses than others. In those with Alzheimer's disease, the leading cause of dementia, the brain develops characteristic sticky clumps, or plaques, of a substance called amyloid-beta. These plaques are clearly visible in the brain during an autopsy.

Yet puzzlingly, studies have shown that a third of people have the brain pathology of Alzheimer's at autopsy, yet never experienced symptoms of cognitive decline during their lifetime. Therefore, scientists say, something must be protecting their brains from succumbing to the toxins.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

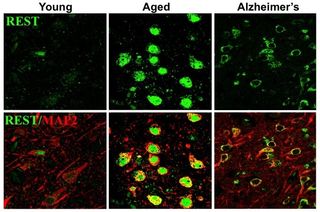

Yankner and colleagues found that the protein known as REST (short for "repressor element 1-silencing transcription factor") turns off genes involved in cell death and resistance to cellular toxins. REST, which is normally produced during brain development, is very active in aging brains, but appears to be missing in the brains of people with cognitive impairment or Alzheimer's disease.

The researchers measured levels of the REST protein in the postmortem brains of people who had taken tests of cognitive function, and found that at death, people with higher cognitive function had three times more of this protein in their prefrontal cortex, the outer frontal part of the brain involved in planning, personality and other cognitive functions.

The finding suggests that plaques and other clinical signs of Alzheimer's may not be sufficient to cause dementia, Yankner said, and it appears that the loss of protective proteins may also be at work.

The REST proteins are like the police officers of the brain, protecting it from aging stresses by turning certain genes on or off, Yankner said. "You have a lot of crime in the brain, but society doesn't fall apart until the police station is blown up," he said.

To explore the role of REST in living animals, the researchers bred mice that lacked the REST gene, and found that these mice were more vulnerable to aging stress and lost a significant number of neurons in the forebrain cortex, one of the primary brain areas affected by dementia. When the researchers restored the REST gene to the mice, it protected the animals from developing cognitive decline.

Yanker's team also studied the effects of stress in the roundworm Caenorhabditis elegans. They found that worms that lacked proteins similar to REST became more vulnerable to stress and had shorter life spans than normal worms. This suggests the protective function has been conserved by evolution.

Preventing cognitive decline

The researchers found that the protein isn't actually gone from brains of people with Alzheimer's. Instead, their brain cells continue to produce REST proteins, but cellular machinery called autophagosomes engulf the proteins and degrade them.

Consequently, it may be possible to intervene and prevent the degradation of these proteins, bringing scientists closer to diagnosing or preventing Alzheimer's disease and dementia.

The researchers are now investigating whether levels of REST protein could be used as a diagnostic of brain health. By looking at how much of this protein is produced in other cells of the body, it may be possible to infer changes in the brain, the researchers said.

Follow Tanya Lewis on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Most Popular