Bee Fossils Provide Rare Glimpse into Ice Age Environment

A new analysis of rare leafcutter-bee fossils excavated from the Rancho La Brea Tar Pits in Southern California has provided valuable insight into the local environment during the last Ice Age.

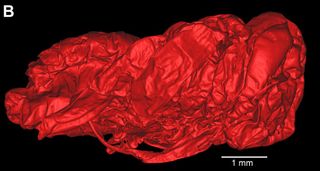

The La Brea Tar Pits, located in Los Angeles, contain the world's richest deposits of Ice Ace fossils, and are best known for their collection of saber-toothed cats and mammoths. In the new study, researchers used high-resolution micro-computed tomography (CT) scanners to analyze two fossils of leafcutter-bee nests excavated from the pits.

By examining the nest cell architecture and the physical features of the bee pupae (stage of development where the bee transforms into an adult from a larva) within the leafy nests, and cross-referencing their data with environmental niche models that predict the geographic distribution of species, the scientists determined their Ice Age specimens belonged to Megachile gentilis, a bee species that still exists today. [Gallery: Dazzling Photos of Dew-Covered Insects]

"Based on what we know about them today and the identification of fossilized leaf fragments, we know that their habitat at the Tar Pits was at a much lower elevation during the Ice Age," said Anna Holden, an entomologist at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County (NHM), and lead author of the new study, published today (April 9) in the journal PLOS ONE. The La Brea Tar Pitswere once a moist, woody habitat that may have also had streams or a river, she added.

Leafcutter bees

Unlike honeybees and other colony-dwelling bees, leafcutter bees are solitary. To reproduce, females build small, cylindrical nest cells made of carefully chosen leaves and sometimes flower petals. The nests "look like mini cigars," Holden told Live Science. The bees build these multilayered nest cells in secure locations near the ground, such as under the bark of dead trees, in stems or in self-dug burrows or those dug by other insects.

In 1970, when scientists first excavated the two nest cells analyzed in the new study, the cells — together known as "LACMRLP 388E" — were connected with an additional layer of leaves. LACMRLP 388E was initially thought to be buds, and only later, after the two cells were accidentally separated, did people suspect they might be bees.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

When Holden first came across the fossils in NHM, she immediately thought they were leafcutter bees, and subsequent X-rays showed they contained pupae — one male and one female. She decided to try to identify the bees' species.

"I had read some of the big literature that said leafcutter bees aren't really identifiable by their nest cells," Holden said. "But I thought, 'That just can't be true; there's got to be a way.'"

Holden paired up with leafcutter-bee expert Terry Griswold, an entomologist with the U.S. Department of Agriculture, to try to pinpoint characteristics that distinguish between the nest cells of different leafcutter bee species.

Piecing the evidence together

The researchers pored over the scientific literature and examined micro-CT scans of the bee nest cells, and discovered there are some differences in the way different leafcutter bees make their cells.

Usually, the oblong leaves that form the side walls of the cell are bent into a cup at the bottom, which is glued together with saliva and leaf sap; at the other end of the cell is a cap made of layered circular discs. However, the nest cells of LACMRLP 388E contained the cap as well as an uncommon circular base, which was also made of circular discs.

This finding narrowed down the possible bee species. The size of the cells and their vegetative components, such as the lack of flower petals and the type of leaves included, further constrained the species list.

After also considering the physical features of the pupae, Holden, Griswold and their colleagues concluded that the pupae had to be Megachile gentilis, a species that currently lives mostly in the southeastern U.S. and northern Mexico. To double-check their identification, and ensure the bees didn't belong to the next-best-candidate species, M. onobrychidis, the team turned to environmental niche models.

"We basically crunched the numbers and projected their habitats onto a geographic map," Holden said.

They found, essentially, that M. gentilis was far more likely than M. onobrychidis to have lived in the La Brea area 23,000 to 40,000 years ago (the approximate age of the excavated nest cells).

Understanding climate change

Unlike other types of fossilized animals, such as mammals and birds, insect fossils can provide valuable clues to ancient environments and climates, Holden said. These animals have well defined life cycles and tight climate restrictions, and aren't likely to migrate if the climate shifts.

"Whenyou find small organisms like insects, you know that's where they lived; that was their habitat," she said.

The nest cells of LACMRLP 388E were constructed underground (but near the surface) in an area adjacent to the fossil-rich Pit 91. The bees didn't simply fall into a tar pit; they were placed into the ground purposefully. The researchers believe the mother bee planted her babies near an asphalt pipe, and the pupae became embalmed in an asphalt-rich matrix when oil soaked into the sediment around the pipe.

This suggests M. gentilis lived in the area, and looking at how the species lives today reveals what the environment and climate were like at La Brea thousands of years ago. After doing so, Holden and her team concluded that the leafcutter bees lived in a low-elevation, moist environment during the Late Pleistocene. Leaf matter used to construct the nest cells likely came from trees not far from the nest site, suggesting the La Brea Tar Pits had a nearby forest, possibly containing streams or a river.

Further research into insect fossils at the La Brea Tar Pits will help scientists gain an even better understanding of the past environment in the region, which could provide insight into what the environment will be like in the coming years. "Understanding climate change in the past will help us understand current climate and environment change," Holden said.

Follow Joseph Castro on Twitter. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Most Popular