Shipwrecks and Dead Trees Become Home for Deep-Sea Life

Sunken dead trees and wooden debris are rare food sources in the otherwise empty abyss of the deep seafloor. Now, a new study shows how this debris becomes home to thousands of squirming sea creatures.

Wood regularly flows into rivers each year after large storms, eventually drifting to sea. There, the wooden debris becomes waterlogged and sinks — sometimes thousands of meters deep — and settles on the seafloor. Bacteria and larval animals quickly colonize these so-called wood falls, using the wood as a source of energy.

Researchers have long known that these wood falls support marine life in this way. However, scientists still know little about the types of animals that live on the wood, and the significance of wood falls in ocean biodiversity, mainly because wood falls are very difficult to locate. [See Photos of the Deep-Sea Wood Fall Creatures]

"Finding an actual wood fall in the ocean is like the proverbial needle in a haystack," said Craig McClain, a researcher at the National Evolutionary Synthesis Center in North Carolina.

McClain recently teamed up with a researcher at the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute in California to study how wood falls promote seafloor life. They placed 36 bundles of acacia tree logs of varying sizes at a depth of nearly 2 miles (3.2 kilometers) in the northeastern Pacific Ocean, and let the logs sit for five years. The researchers checked the logs annually with an underwater robot called a remotely operated vehicle (ROV).

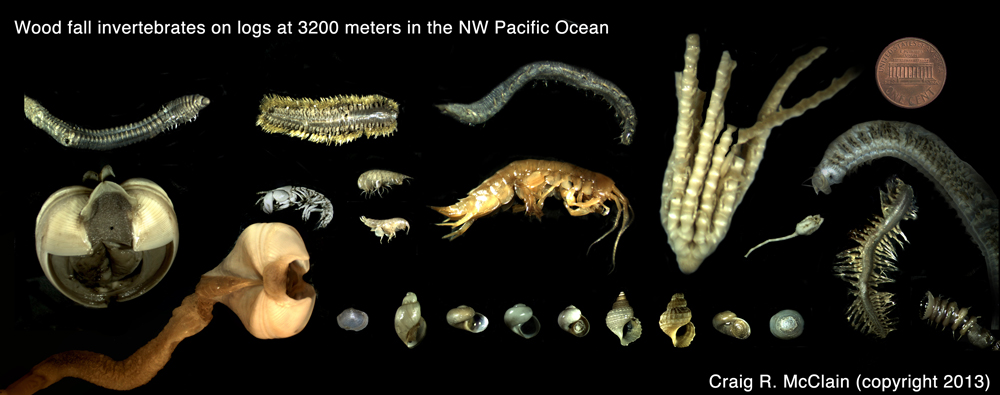

The researchers found that a species of clamlike bivalve (an animal with two protective shells), Xylophaga zierenbergi,was often the first creature to colonize the wood. The clams live inside holes they bore into the wood, giving the logs a honeycomblike texture. The wood chips and fecal material produced by the bivalves provide food for bacteria that grow in mats. The bacteria then provide food sources for other types of animals. The broken-down logs ultimately attract dozens of different species of bacteria, worms and crustaceans — including a long-clawed crab called a galatheid — that make homes in the holes bored by the bivalves and the surrounding seafloor sand.

The researchers have now retrieved the logs from the seafloor and are in the process of analyzing the deep-sea squirmers that inhabited the wood. The team has already discovered one new species of shrimplike crustacean called a tanaid, as well as several worms that may also be new to science.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Each log hosted as many as 30 species, which is not a particularly large number compared with the multitude found in other regions of the ocean, McClain said. However, the logs did contain an unusually large number of individuals within specific species, the team reports.

"A single wood fall may have 1,000 individuals of this tiny snail, and you would never find anything in the background that would have that number of individuals," McClain told Live Science. More typically, only two or three snails of that species would inhabit a given square meter (about 11 square feet) of the seafloor at that depth, McClain said.

The researchers next hope to try to estimate the total biomass — or living material — that inhabits wood falls worldwide, in an effort to understand wood's role in the total biodiversity of the ocean, McClain said.

The study findings were published April 5 in the journal Biology Letters.

Follow Laura Poppick on Twitter. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.