Sustainable Ranching: Where Cows and Capybara Roam (Op-Ed)

Julie Kunen is executive director for WCS's Latin America and Caribbean Program. She contributed this article to Live Science's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

If there is one thing that Americans know about the environment of Brazil, it is the decimation of Amazon forests for ranching and agriculture. But what if I told you that there is a place in Brazil where cattle graze on native grasses seasonally replenished by an annual flooding cycle, where ranches are dotted with lakes full of fish, where rivers support giant river otters and where forests line riverbanks and form highways for jaguars and other rare species?

This place, the Pantanal, is the vast, low-lying alluvial plain of the Alto Paraguay River, one of South America's mightiest waterways, which is born on the surrounding highlands, courses through the immense lowlands of the Pantanal basin, and joins the Paraná River before draining into the southern Atlantic Ocean.

It is unique enough to have been designated both a UNESCO World Heritage Site and a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve, and it contains several globally important wetlands. Yet — with the exception of serious birders attracted to its rare and abundant bird life — most people have never heard of it. That is a shame.

Due to the openness of the Pantanal's terrain, it is easy to see animals that are nearly impossible to spot in the Amazon , as I did on a recent visit. In the course of a single day and night, I saw hyacinth and blue-and-yellow macaws, brocket deer, white-lipped peccary, rhea, jabiru stork, roseate spoonbill, wood stork, the greater potoo, capybara, tapir and giant anteater.

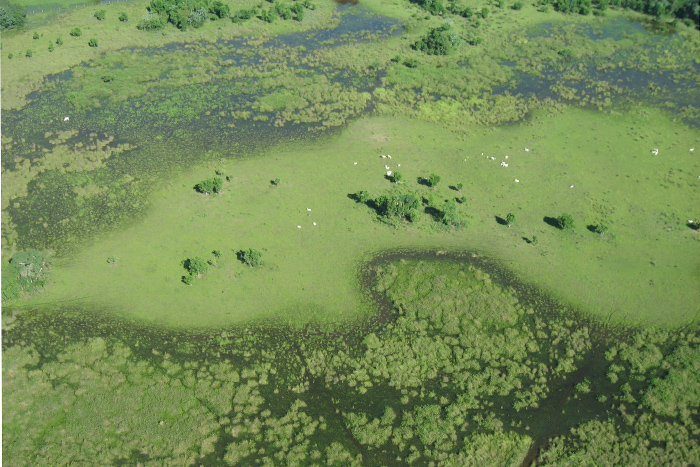

The traditional way of life in the Pantanal for nearly two centuries has been ranching. Typical ranches are quite large and include extensions of seasonally flooded grasslands, small lakes and "cordilheira" forests — patches of forest occupying land just high enough to avoid flooding. These forests provide food (especially fruiting trees), habitat and connectivity to other patches of forest for wildlife.

In some cases, these forests form very long corridors across multiple ranches running hundreds of kilometers. Researchers from the Wildlife Conservation Society have documented use of the corridors by white-lipped peccaries, an important "indicator species" that reveals much about the health of the ecosystem. I call these corridors the great peccary highways.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Sadly, this traditional way of life is under threat from two principal trends. First, children inheriting ranches from their parents are subdividing their properties. But the traditional ranching system, which depends upon large expanses of native grasslands, is not sustainable on smaller and smaller parcels.

Possible solutions to this problem include collaboration among siblings on neighboring ranches (rare, but doable); buying out of one sibling by another, particularly in cases where not every brother or sister wishes to continue a rural lifestyle; and supplementing income with other activities, such as ecotourism .

Second, market pressures encourage the intensification of ranching in order to gain more profit. This takes two primary forms, both damaging to the natural ecosystem and its animal inhabitants.

Some ranchers plow under the native savannas and plant exotic grasses that can support denser stocking. These introduced pastures destroy species-rich native grasslands. Other ranchers cut down forests and drain wetlands to expand their grassland area. Deforestation causes erosion, alters water balance, eliminates the food and habitat that wildlife need, and increases the chance of conflict between people, their cows, and predators with fewer and fewer prey options.

There are ways to preserve the traditional ranching way of life in the Pantanal that protect its magnificent wildlife populations. WCS researchers have developed and tested successful systems of rotational grazing on native grasslands that increase economic productivity and also protect native habitat. Such systems should be adopted more widely, but ranchers may need assistance with the up-front costs of transitioning to the new system.

New markets could recognize and differentiate Pantanal beef grown on native pastures from other types of grass-fed beef that do not identify whether or not the grass in question is native or an introduced exotic. If consumers understand and care enough about the difference to buy native grass-fed beef, ranchers will have an incentive to stick to traditional methods.

Finally, awareness of the unique success story that is traditional Pantanal ranching should encourage more visitors — birders, wildlife aficionados, families interested in a ranch vacation — to come. What they will find will surely alter their perception of Brazil as a land known more for deforestation than sustainable ranching that supports rather than undermines the protection of local wildlife. Needless to say, that is a practice — like this story — that bears repeating.

Follow all of the Expert Voices issues and debates — and become part of the discussion — on Facebook, Twitter and Google +. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This version of the article was originally published on Live Science.