19th-Century Circus Train Crash Mystery: Where's the Animal Graveyard?

The first car to go off the rails held the elephants.

The tigers, lions, horses, crocodiles, pythons and a gorilla known as the "Man-Slayer" followed as the Walter L. Main circus train careened off the tracks down a 30-foot-high (10 meters) embankment, with gold-gilt, steel-barred wagons crashing one on top of the other in the legendary pileup at Tyrone, a small town in central Pennsylvania, on Memorial Day 1893.

Today, the story has become ingrained in town lore. Big snakes are eyed with suspicion as possible descendants of escaped crash survivors. Elephants from other traveling circuses have stopped in Tyrone to lay wreaths out of respect for the dead. Bones, horseshoes, lion-cage locks and railroad spikes have turned up every time a new home is built on the site. But the exact location of the mass grave of dead circus animals has been lost to history. Archaeologists recently made an attempt to find it. [See Photos of the Tyrone Circus Train Wreck]

An initial search didn't turn up the hoard of bones researchers were looking for, but the team hopes further investigations will shed light on the crash.

"It was a little bit disappointing, but now we know where it isn't," local historian Paula Zitzler said.

Zitzler, who teaches at Penn State Altoona and wrote a book on the train crash, recently worked with a group of graduate students from Indiana University of Pennsylvania to probe a stretch of land near the accident site.

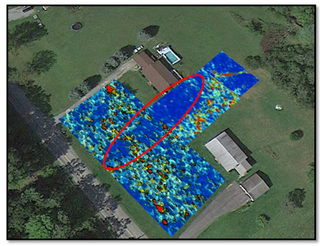

Using ground-penetrating radar, the students scanned 12,450 square meters (about 3 acres) of private property. The team said they found an intriguing anomaly with a lower metal content than the surrounding soil, but bad weather kept them from digging large test pits. They did pull a few cores of dirt out of the ground, but these samples were inconclusive.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The students — Michelle Cole, Daniel Sandrowicz, Katharine Craig, Kate Adam and Kirk Smith — presented the results of their investigation, which was part of a class project, last weekend at the annual meeting of the Society for American Archaeology in Austin, Texas.

Runaway trains and runaway tigers

If archaeologists eventually uncover the grave, it's not clear exactly what they'll find. While researching the accident, Zitzler said it was difficult to get a full inventory on the casualties.

The train was traveling west down a slope of the Allegheny Front, approaching a bend that was notorious for crashes, Zitzler said. While 17-car coal trains could manage the steep mountainside with just one locomotive, many of the 17 cars on the Walter L. Main circus train were twice as long as the average coal car. The engineers wired ahead to request more braking power but were denied. As they guided the train down the slope, it quickly picked up speed and couldn't be stopped. The locomotive at the front made it around the curve, but the cars behind it flew off the tracks near a farm owned by a man named Hiram Friday. [The 7 Most Mysterious Archaeological Finds on Earth]

Remarkably, only five people were killed. The train essentially piled up to the level of the tracks, Zitzler said, and the last few cars, where most of the circus performers rode, didn't go off the rails.

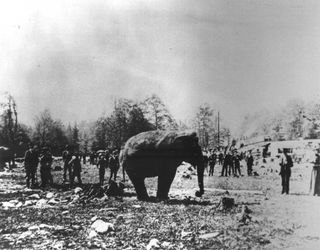

The animals, mostly at the front of the train, bore the brunt of the suffering. Two "sacred cows" and at least 50 horses were killed. (The traveling circus was known for its horse acts, such as chariot races and juggling shows performed on the animals' backs.) The elephants survived, albeit with some injuries, and the sturdy beasts were even put to work in the accident cleanup. The Man-Slayer lived through the accident, too; Zitzler said there are photos of the unhappy gorilla tied to a tree after the accident.

Other animals survived the crash only to be killed after they bolted from their broken cages. In the most famous incident, Hiram Friday's daughter Hannah was milking a cow a few days after the wreck when a Bengal tiger attacked and killed the cow. Friday was injured while fighting in the Civil War and forbid guns in his home, said his great-granddaughter Susie O'Brien, who lives on the property today. A bear hunter had to be called in to find the tiger in the nearby woods and shoot it. The beast's skull hangs in a local hunting club today. [8 Grisly Archaeological Discoveries]

Still more escapees may have evaded capture altogether. In the months and years after the accident, the local papers were peppered with reports of exotic animal sightings. In the nearby town of Warriors Mark, people on their way to church one Sunday morning reportedly saw three kangaroos hopping across the street. Men who went out fishing would say they saw strange birds, likely parrots, that made the treetops look as if they were dabbed with colorful paint, Zitzler said. A year after the accident, on Ascension Thursday (celebrated by Christians as the day Jesus ascended into heaven), revelers at a barn-raising at the Friday farm reportedly left before dark out of fear the circus animals were still lurking on the property.

The show must go on

While the lore lingered for decades, the wreckage from the accident was cleared in just three days. Amid the swift cleanup, the dead animals were buried in trenches on the Friday farm along with other wreckage too mangled to be reused. But there is no documentation of the mass grave's exact location.

O'Brien, who has been giving presentations about the wreck since 1993, has amassed a collection of artifacts found on her property and the nearby plots owned by her relatives, including bone bits, horseshoes and even an antique donkey-shaped bottle opener, perhaps from the dining car. Her goal has always been to conduct a study — perhaps a dig —at the site.

"I'm just curious to see what survived," O'Brien told Live Science. "I thought there might be interesting artifacts."

Zitzler said she thinks it would be interesting to dig a few tests pits around the site of the anomaly the students found, or expand the search to a wider area. But in her eyes, the most interesting part of the crash is perhaps not the elusive grave, but the social disturbance it caused in its immediate aftermath.

The circus was stranded in Tyrone for a week while the train cars were being fixed at the nearby railroad shop in Altoona. (Despite the horrible accident, the show did go on.) The Industrial Revolution was a period of not only technological transformation, but also heavy immigration, and the circus performers — many of them likely Europeans — may have raised suspicions among the people of Tyrone.

"I like to think of the circus performers in sequins and tights walking down the unpaved main street of Tyrone — and the townspeople looking and closing their doors," Zitzler said.

But some of the performers got along fabulously with the locals. O'Brien said her great-great-uncle befriended a clown who survived the wreck and came back to the farm every May for the memorial service for the victims that was held each year from 1895 to 1958.

O'Brien helped reinstate that tradition in 2009 with a ceremony at the crash site. When two elephants laid wreaths at the memorial, they cried out to each other, O'Brien said, and their trainer claimed they could sense they were on a burial ground.

"But circus people tend to enhance everything," O'Brien said.

Follow Megan Gannon on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Most Popular