Fracking-Linked Earthquakes May Strike Far from Wells

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

ANCHORAGE, Alaska — Fracking may cause earthquakes much farther from the sites of its wastewater wells than previously thought, researchers said here Friday (May 2) at the annual meeting of the Seismological Society of America.

In central Oklahoma, a cluster of four high-volume wastewater injection wells triggered quakes up to 30 miles (about 50 kilometers) away, said lead study author Katie Keranen, a geophysicist at Cornell University in New York. The earthquakes have since spread farther outward, as fluids migrate farther from the massive injection wells, she said.

"These are some of the biggest wells in the state," Keranen said. "The pressure is high enough from the injected fluids to trigger earthquakes."

Scientists here noted the vast majority of injection wells haven't triggered any quakes, and the link between earthquakes and fracking or wastewater injection is not conclusive. However, there are now more earthquakes in the United States than before the fracking boom began. Between 1967 through 2000, there were an average of 21 earthquakes yearly above magnitude 3.0. That rate shot up to an average of 300 earthquakes yearly after 2010. [See Photos of Earthquakes' Paths of Destructions]

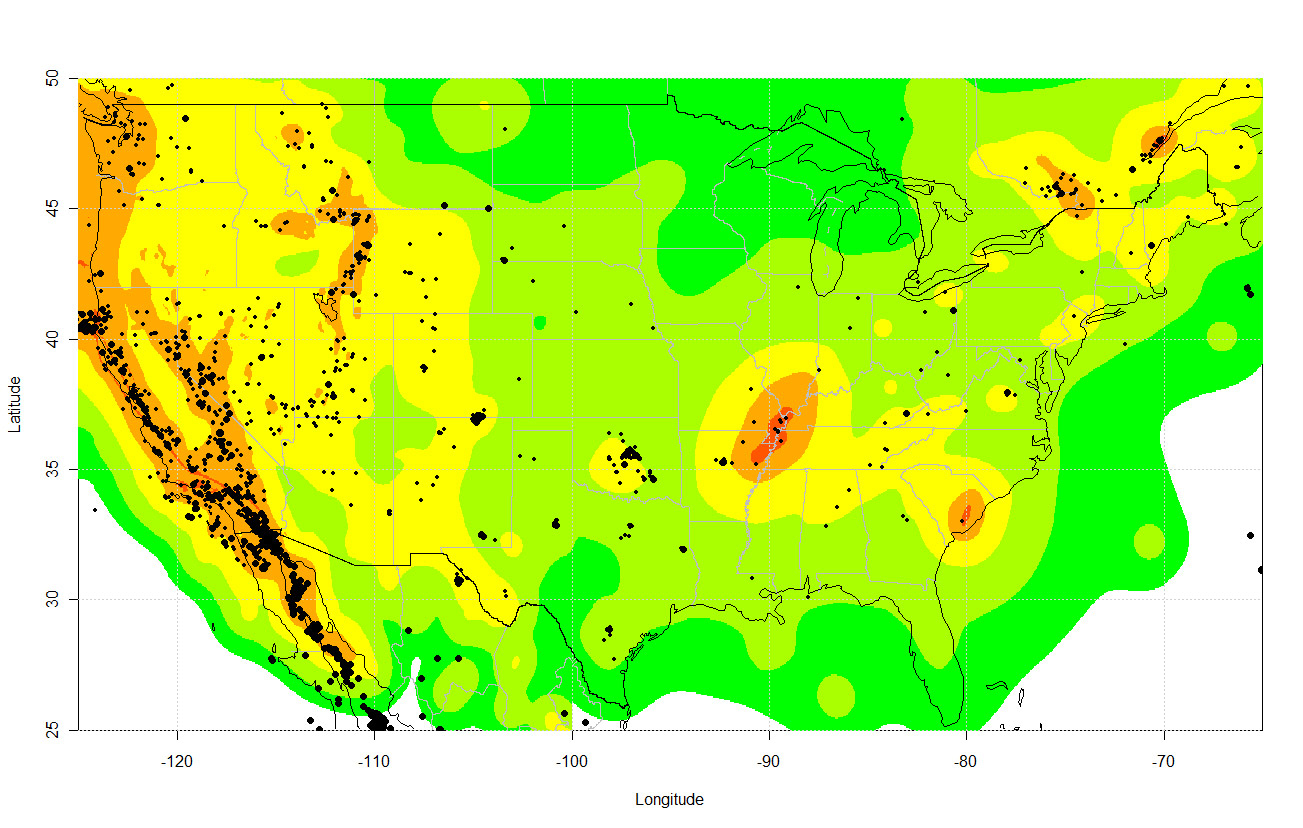

Keranen's new findings were among several studies presented here this week that draw a strong connection between fracking practices and earthquakes. Many geoscientists suspect America's recent sharp increase in earthquakes results from the growth in fracking. Plotted on a U.S. map, earthquakes since 2009 cluster near oil and gas operations in states such as Oklahoma, Ohio, Arkansas and Texas, as well as the usual quake hot zones in the seismically active Western states.

"It looks like the Earth has a case of the chickenpox," said Justin Rubinstein, a geophysicist with the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) in Menlo Park, Calif.

Overwhelming numbers

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Fracking is a method of extracting oil and gas from the ground by fracturing and cracking — or fracking — rocks. The technique involves forcing millions of gallons of water laced with chemicals and sand into underground rock to free trapped oil and gas. After the fracking is finished, the contaminated wastewater is pumped out and injected back into the ground, disposed of in wells that are typically much deeper than the oil and gas reservoirs.

The injected fluid can lubricate buried fault lines and increase "pore pressure" on a fault's surface, making it easier for a fault to slip and cause an earthquake.

"Even though only a small fraction of injection wells do induce damaging earthquakes, there are so many injection operations that these operations have materially contributed to the seismic hazard in the U.S.," said Art McGarr, also a geophysicist with the USGS in Menlo Park. "In states like Oklahoma, where wastewater continues to be injected, I think it's highly likely we will continue to see larger earthquakes there."

In Oklahoma, where a magnitude-5.7 earthquake damaged houses in 2011, the earthquake rate now seems to exceed that of California, once the size of each state is taken into account, said Keranen's study co-author Geoff Abers, a seismologist at the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory in New York.

Evaluating risk

Because of the recent jump in earthquakes, and their significant size, the USGS plans to estimate the national shaking risk from "induced seismicity" for the first time, Rubinstein said. Induced seismicity refers to any man-made earthquake, including fracking, wastewater injection and geothermal plants. [50 Amazing Facts About Planet Earth]

"We've never done this before," Rubinstein said. But "these earthquakes of larger magnitude really demonstrate that [induced earthquakes] are a significant hazard."

The new map will help illustrate something that people who live near wastewater injection wells already know: these shallow, triggered earthquakes are felt more widely and may cause more damage than natural earthquakes.

A natural earthquake can strike at any depth, but typically hit at an average depth of about 6 miles (10 km) in the continental crust, said Gail Atkinson, a seismologist at Western University in Ontario, Canada. In contrast, induced seismicity events are usually 1 to 2 miles (2 to 3 km) deep. "The close distance means that ground motion can be quite strong," Atkinson said.

The rising number of man-made earthquakes may pose a risk to critical infrastructure such as dams and nuclear power plants, according to a study presented by Atkinson on Thursday (May 1). But the danger is still unknown.

"Our experience comes from earthquakes that are much deeper," she said. "There is quite an absence of a regulatory framework in terms of how to evaluate what the hazard is and who is responsible for assessing and responding to it," Atkinson said.

Email Becky Oskin or follow her @beckyoskin. Follow us @OAPlanet, Facebook and Google+. Original article at Live Science's Our Amazing Planet.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus