Images: World's Oldest Petrified Sperm

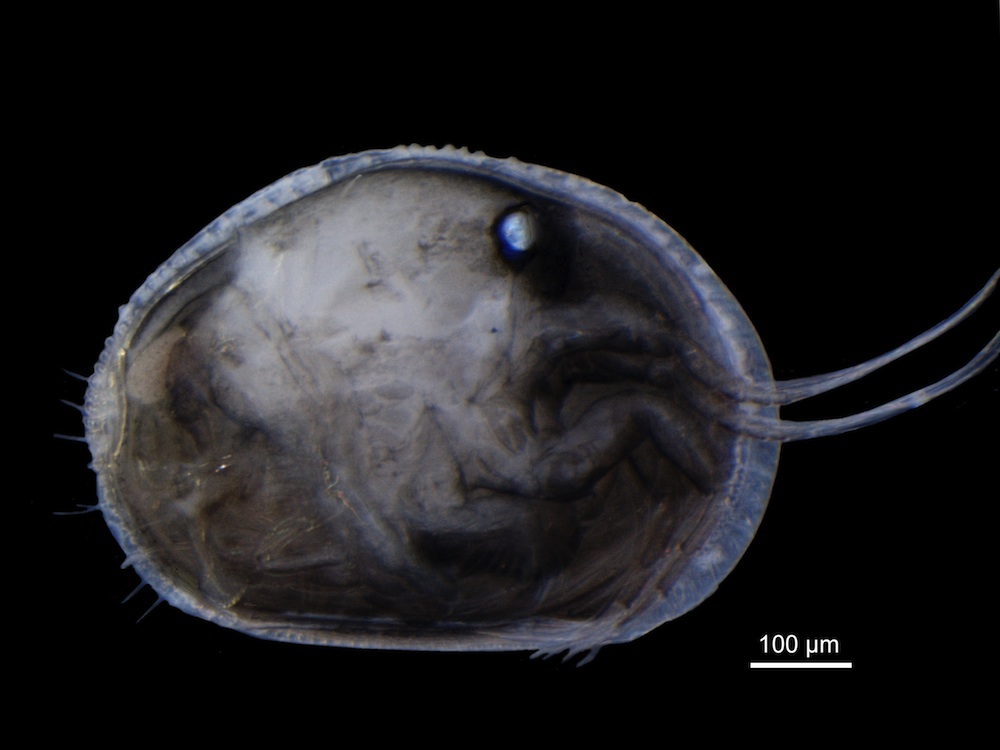

Modern Ostracod

Scientists have discovered the world's oldest petrified sperm, dating to the early Miocene epoch, between about 23 million and 16 million years ago. The relatively giant sperm belonged to a tiny crustacean called a seed shrimp or ostracod. Here, a modern ostracod (Newnhamia). These tiny crustaceans create sperm longer than their own bodies. [Read the full story on the petrified sperm

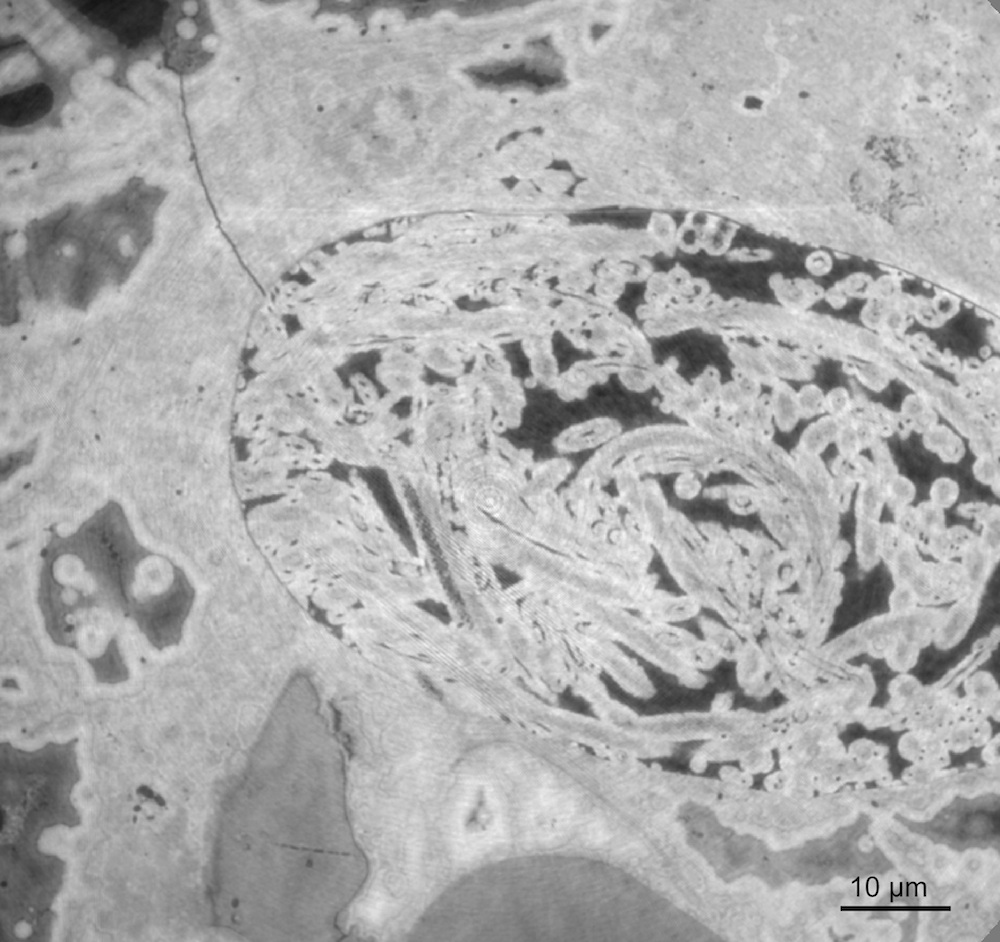

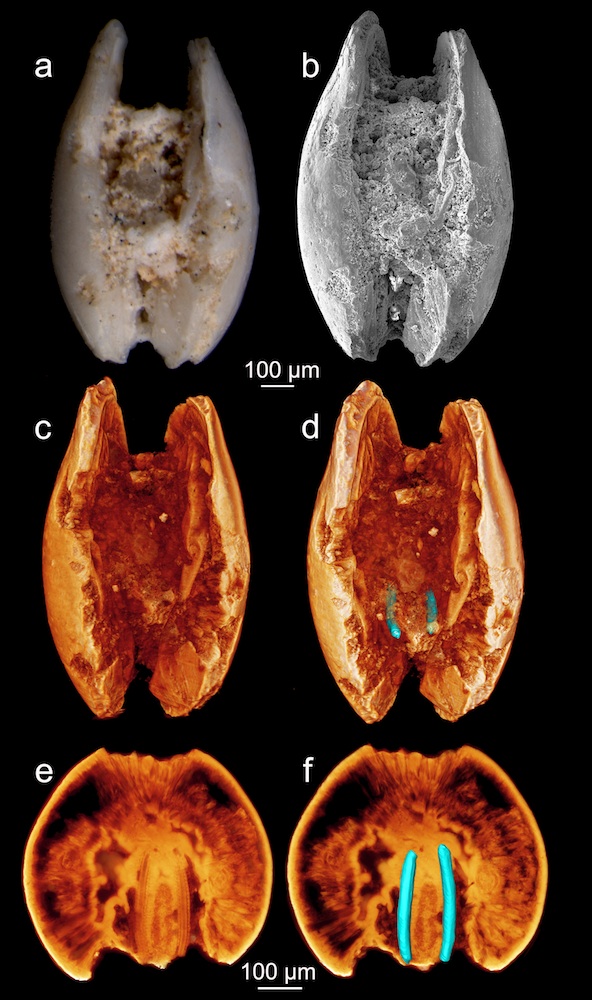

Ancient Sperm

Nanotomography of an ancient female Newnhamia (Newnhamia mckenziana), showing numerous giant sperm preserved inside the seminal receptacles.

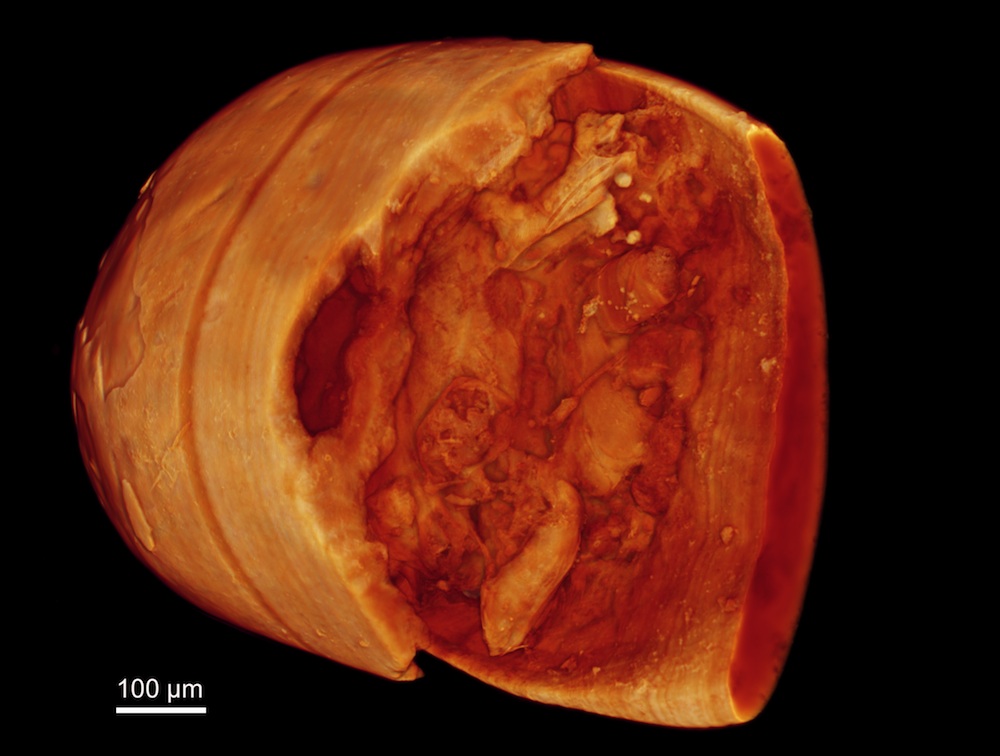

Male Ostracod

A 3D reconstruction of Heterocypris collaris, a male ostracod dating back 16 million years.

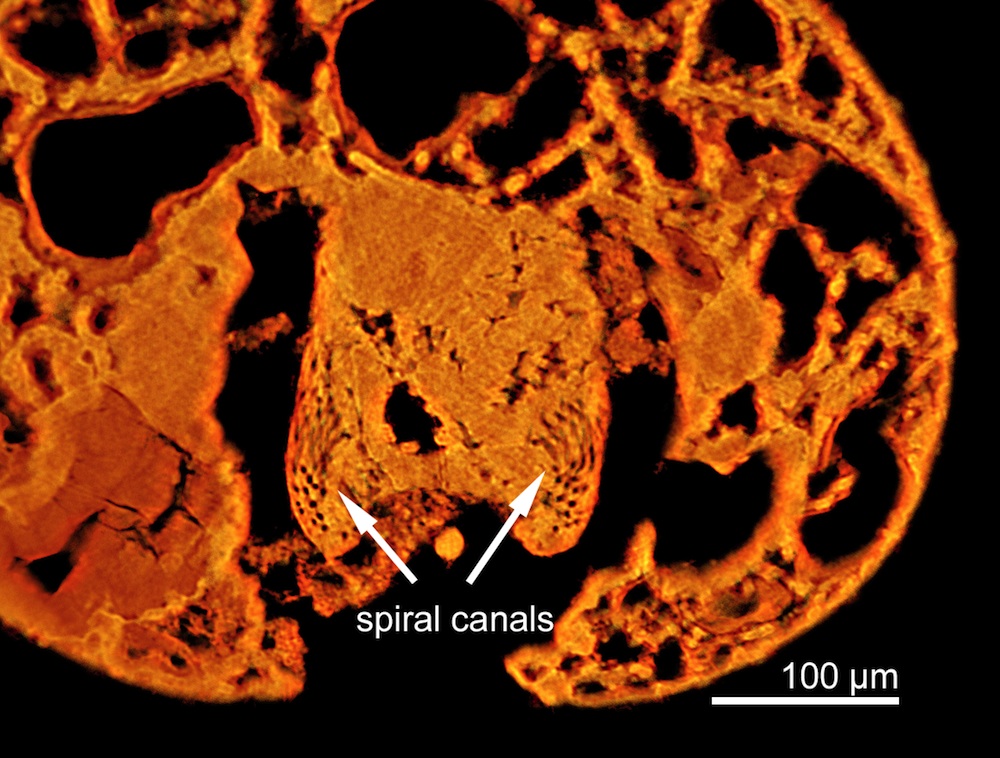

Slice of Ostracod

A virtual slice of a female Newnhamia mckenziana from about 16 million years ago. The arrows point to spiral canals, which are large pathways for a male's giant sperm to travel to reach the female's sperm receptacles.

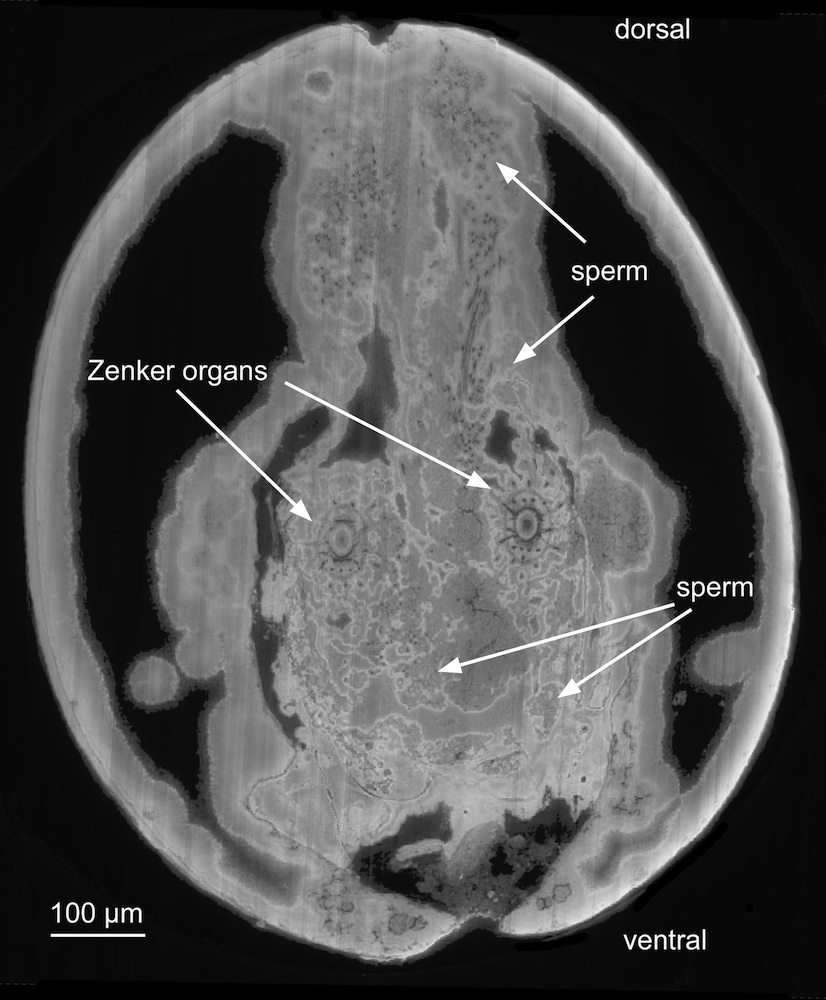

Sperm Cross-Section

,A cross section of a male Heterocypris collaris, showing Zenker organs, which act as sperm pumps, as well as sperm stored in the seminal vesicle and ducts.

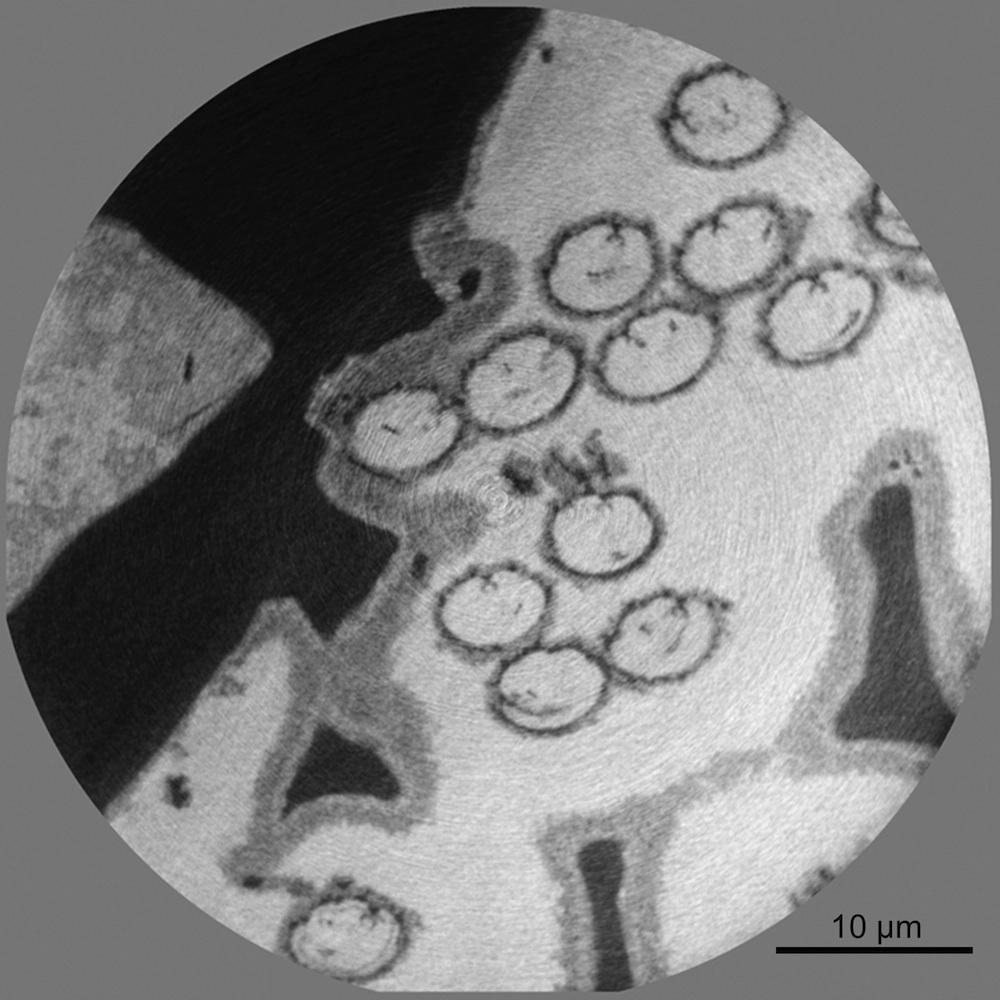

Seminal vesicle

A cross-section of the seminal vesicle of the male Heterocypris collaris, with the nucleus of each sperm visible.

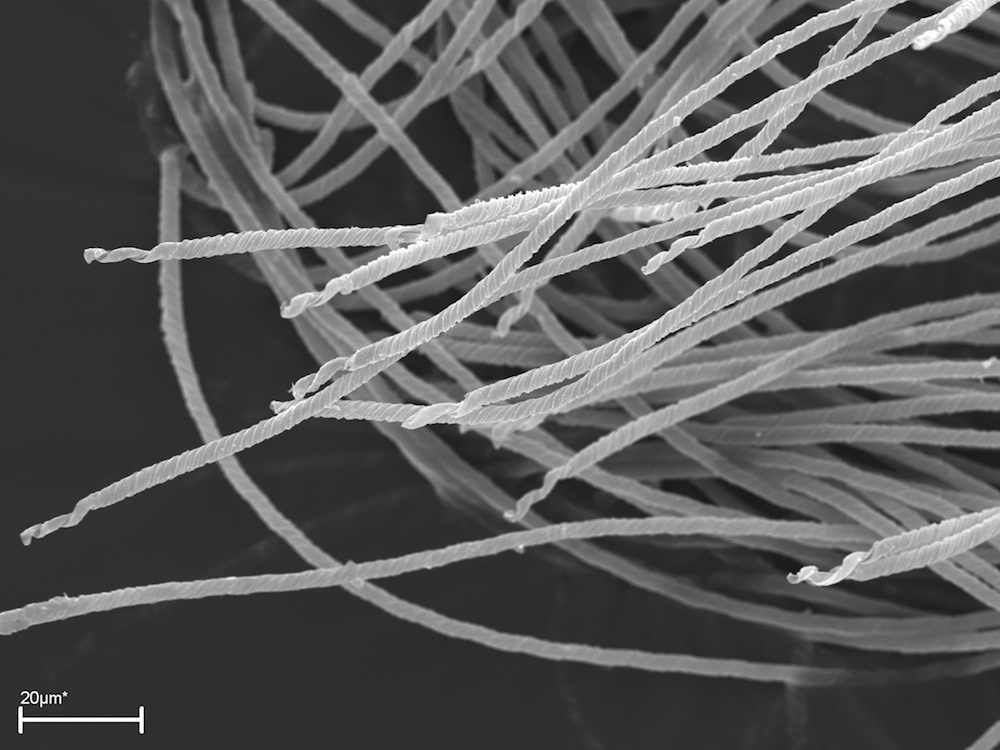

Modern Giant Sperm

A modern analogue: Sperm from today's Australian salt lake ostracod, Mytilocypris mytiloides.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

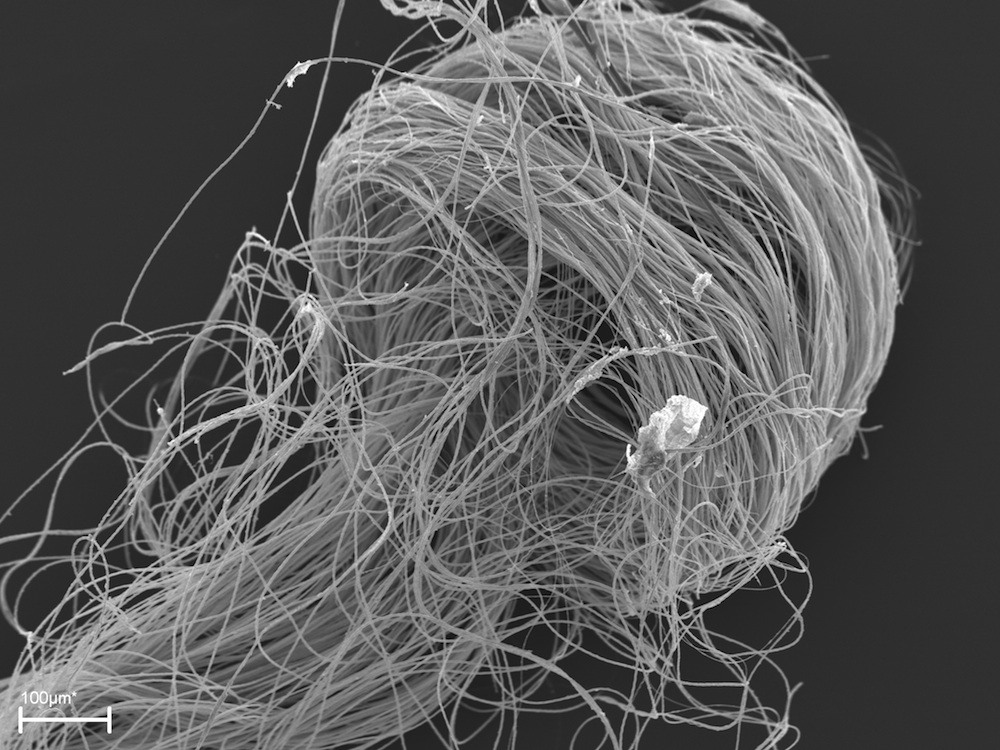

Giant Sperm

A coiled bundle of giant sperm cells from the male’s seminal vesicle of the modern Australian salt lake ostracod, Mytilocypris mytiloides

Modern Eucypris

The modern freshwater ostracod Eucypris virens also uses giant sperm cells for reproduction, although it is not a record holder with sperm being around 1.2 times as long as the male’s body.

Ancient Ostracod

A 16 million-year-old ostracod imaged with a light microscope, scanning electron microscope and with synchrotron microtomography. Blue lines highlight Zenker organs.

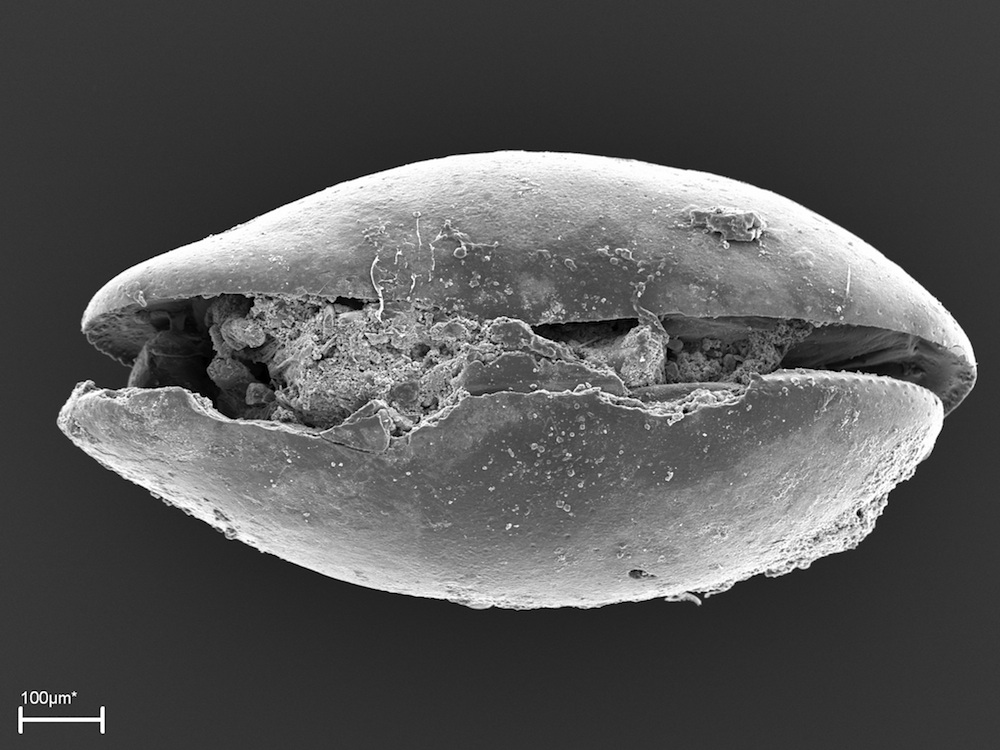

Soft Tissue Fossil

An external view of a 16 million-year-old ostracod with soft tissue preserved.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.