Will New Meteor Shower This Weekend Sizzle or Fizzle?

Meteor observing can be relaxing and enjoyable, yet it's also potentially dramatic. One of its fascinations is that meteors are unpredictable.

Usually they are few and far between, but you never know for sure what will happen next. There's always a chance that you will observe something new and different, rare or unique, whether it be a new meteor shower, a brilliant fireball or a long-enduring smoke train.

That unpredictably is on display this week, with the return of a periodic comet that may bring a spectacular "meteor storm" as well. [New Meteor Shower from Comet 209P/LINEAR (Gallery)]

A new meteor shower is born

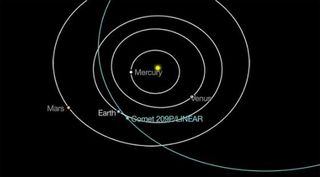

Comet 209P/LINEAR orbits the sun every 5.1 years, with its aphelion (farthest point from the sun) lying just inside Jupiter's orbit. It is a member of Jupiter’s family of comets, which consists of icy bodies whose current orbits are primarily determined by the gravitational influence of the giant planet.

Comet 209P/LINEAR is just one of over 400 Jupiter-family comets known, most of which are extremely faint. This is due to the rapid depletion of their volatiles through multiple trips to the inner solar system, brought about by their short orbital periods. (Jupiter-family comets have orbital periods of less than 20 years.)

We can therefore thank Jupiter for raising the potential of a spectacular meteor shower on Saturday morning (May 24), because the gas giant has clearly shepherded 209P/LINEAR into the orbit we find it in today. Its most recent encounter in February 2012 saw the comet pass within 54 million miles (87 million kilometers) of Jupiter.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

As luck would have it, that 2012 encounter perturbed the comet — as well as any dusty debris presumably near it — into a new orbit that now comes within just 280,000 miles (450,000 km) of Earth’s orbit, possibly setting the stage for a never-before-seen meteor shower.

Indeed, Earth will arrive at the comet's orbital plane at around 2 a.m. EDT (0600) on Saturday. Some believe that a significant meteor outburst will result. Amazingly, the comet itself will pass through this very same region of space just 3 days later!

The meteoroids that crumble off a comet's nucleus form a thin sheet in the comet’s orbital plane. Whenever Earth plunges through this plane, we have a chance for a meteor shower. Whether we get a spectacular "meteor storm," a strong shower or nothing at all depends on exactly what part of the plane we go through.

Editor's Note: If you capture an amazing photo of the new meteor shower, or any other night sky view, that you'd like to share for a possible story or image gallery, please contact managing editor Tariq Malik at spacephotos@space.com.

Sizzle of fizzle: What might we see?

![Learn why famous meteor showers like the Perseids and Leonids occur every year [See the Full Infographic Here].](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/CDt6Bd96e3pUTgR4LE2nXX-320-80.jpg)

Meteor experts have been working hard trying to determine just what Earth's interaction with the dusty debris of Comet 209P/LINEAR will produce. Predictions have ranged anywhere from 100 meteors per hour to perhaps a full-fledged meteor storm of 1,000 per hour.

In weather forecasting, meteorologists sometimes make analog forecasts — comparing scenarios from the past to upcoming events. So I thought I might throw my own forecasting hat into the ring by trying to calibrate the intensity of Saturday's potential meteor event with one from the past, using a well-known meteor-producing comet.

That comet is 21P/Giacobini-Zinner. Another member of Jupiter's comet family, it orbits the sun every 6.6 years and was responsible for one of the greatest meteor displays in the 20th century — the tremendous "Giacobinid" meteor storm of 1946. [How Meteor Showers Work (Infographic)]

On the evening of Oct. 9, 1946, North American time, Earth passed within 139,000 miles (220,000 km) of the comet's orbital plane, reach this point in space 15 days later than the comet. Interestingly, that orbital geometry was not too different from what we're about to experience with Comet 209P/LINEAR. In the case of the Giacobinids, meteor activity shot up after dark and ultimately reached a sharp peak of 50 to 100 meteors per minute (3,000 to 6,000 per hour) despite hindrance by the light of a full moon!

Might we expect to see a similar display this coming Saturday morning? Unfortunately, the answer is probably not.

Comet 21P/Giacobini-Zinner is considerably larger than Comet 209P/LINEAR and expels much more dust into space, dust that ultimately translates into meteors. In fact, as comets go, 209P/LINEAR is a rather puny specimen, estimated to be just 0.37 miles (0.6 km) wide. That's only about 1/7 as large as 21P/Giacobini-Zinner.

Based on a proportional scale, that would suggest a rate of about 400 to 800 meteors per hour. That still would amount to quite a show, except ...

Hitting the old dusty trails

The trails of Comet 21P/Giacobini-Zinner dust that produced the dramatic 1946 meteor storm were relatively fresh, having made just two to seven complete revolutions around the sun over a span of 13 to 46 years.

Meanwhile, the dust trails ejected by Comet 209P/LINEAR for next Saturday’s expected encounter have made anywhere from 18 to 42 trips around the sun over the space of 90 to 211 years. Trails of dust that have been recently released into space tend to be more densely clustered together as opposed to older trails, which have had more time to become more widely dispersed.

So the end result should be a much less intense meteor shower, with possible rates of perhaps 50 to 100 per hour — on par, perhaps, with the annual August Perseids or December Geminid showers. That might be the best we could hope for next Saturday. [Amazing Photos of the 2013 Geminid Meteor Shower]

But perhaps we just might be able to improve on those numbers. The possible reason? Jupiter!

A theory that resonates

Recently, while doing some orbital simulations of Comet 209P/LINEAR for the past two centuries, I noticed that Jupiter had perturbed this comet’s orbit no fewer than five times: In 2012, 1976, 1917, 1881 and 1845. Take note that most of these perturbations are separated by intervals of 36 years, the equivalent of three revolutions around the sun by Jupiter.

Many comets and asteroids swing around the sun in orbits that are simple multiples of the orbital period of Jupiter, the most massive planet in the solar system and the biggest disturbing influence on cometary orbits. Comet 209P/LINEAR is no exception to this rule. For every three revolutions of Jupiter, comet 209P/LINEAR makes seven, and the same relation probably holds true for the dust particles released by the comet.

These dust particles therefore have average orbital periods very close to that of the comet, and might be kept in step by the influence of Jupiter; they avoid spreading out as a result of a dynamical process known as resonance, analogous to the mechanism leading to the fine structure seen in Saturn's rings.

For an analogy, consider a pool table with balls in a rack. When the rack is lifted, the balls slowly scatter, representing what happens to the dust particles released into space by the comet. But when the comet and its accompanying particles pass near Jupiter, the big planet "re-racks" the particles, bringing them closer together again.

Meteor showers can be awesome night sky sights, but how well do you know your shooting star facts? Find out here and good luck!

Meteor Shower Mania: How Well Do You Know 'Shooting Stars'?

Resonance then, is the wild card for our upcoming meteor display. It can mean the difference between a mildly entertaining meteor shower and a very exciting one. If the dust particles shed by Comet 209P/LINEAR are drawn together thanks to repeated passages by Jupiter, we might be treated to many hundreds of meteors per hour.

Regardless of just how many are seen, the meteors are likely to bright and very slow moving.

They'll be bright because computer simulations suggest the comet's trail of dust should be skewed toward relatively large particles, possibly leading to some outstandingly bright fireballs.

And they'll be slow because the meteors will hit the atmosphere at a mere 40,000 mph (64,000 km/h), so they'll appear to move slowly and majestically across the sky — far more slowly than the Leonids and Perseids.

Finally, moonlight will be a minor hindrance at most. The moon is a waning crescent 4 1/2 days from now, just 20 percent illuminated, and it doesn’t rise until around 3 a.m. So hope for fair skies, plan your observing site and be ready for whatever happens in the early hours of Saturday morning. Nobody knows what will happen.

Only two things we can say with certainty: The skies will be dark and the meteors bright.

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmer's Almanac and other publications, and he is also an on-camera meteorologist for News 12 Westchester, N.Y. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.