Transparent Snails & 'Fairy' Wasps: Top 10 New Species Revealed

A fuzzy-faced, tree-living carnivore, a transparent snail and ice-clinging anemones are among the top new species discovered in the last year.

The 2014 top 10 list, put together by the International Institute for Species Exploration at the SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry, highlights the most amazing species discovered in 2013. According to the institute, this year's Top 10 New Species come from a field of 18,000 newfound species named in 2013.

"The top 10 is designed to bring attention to the unsung heroes [who are] addressing the biodiversity crisis by working to complete an inventory of Earth's plants, animals and microbes," Quentin Wheeler, the president of the college, said in a statement. "Each year a small, dedicated community of taxonomists and curators substantively improves our understanding of the diversity of life and the wondrous ways in which species have adapted for survival." [See Photos of the Top 10 New Species]

Beautiful beasties

The species honored with a place on the top 10 list range from plant to animal to fungus. Perhaps the cuddliest is the olinguito (Bassaricyon neblina), a mini-carnivore that lives in the trees of Andean cloud forests. The animal had been known for decades and even shown in zoos, but it wasn't until researchers did a thorough examination of the skulls of this creature and its relatives that the scientists noticed they had a new species on their hands.

Meanwhile, in Antarctica, scientists with the Antarctic Geological Drilling Program (ANDRILL) stumbled upon something bizarre while piloting remotely operated underwater vehicles beneath the ice sheet: The underside of the ice looked fuzzy.

A closer look revealed sea anemones, their bodies burrowed into the ice and tentacles extended to filter-feed from the water below. The species, dubbed Edwardsiella andrillae, is the first-ever anemone known to live on ice.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Transparency is a theme for two other new species. The itsy-bitsy shrimp Liropus minusculus was found in a cave on Santa Catalina Island off the coast of California. The males of the species are only about an eighth of an inch (3.3 millimeters) long, and females are less than a tenth of an inch (2.1 mm). The shrimp have translucent bodies, and creep like inchworms along rocks in shallow tidal zones.

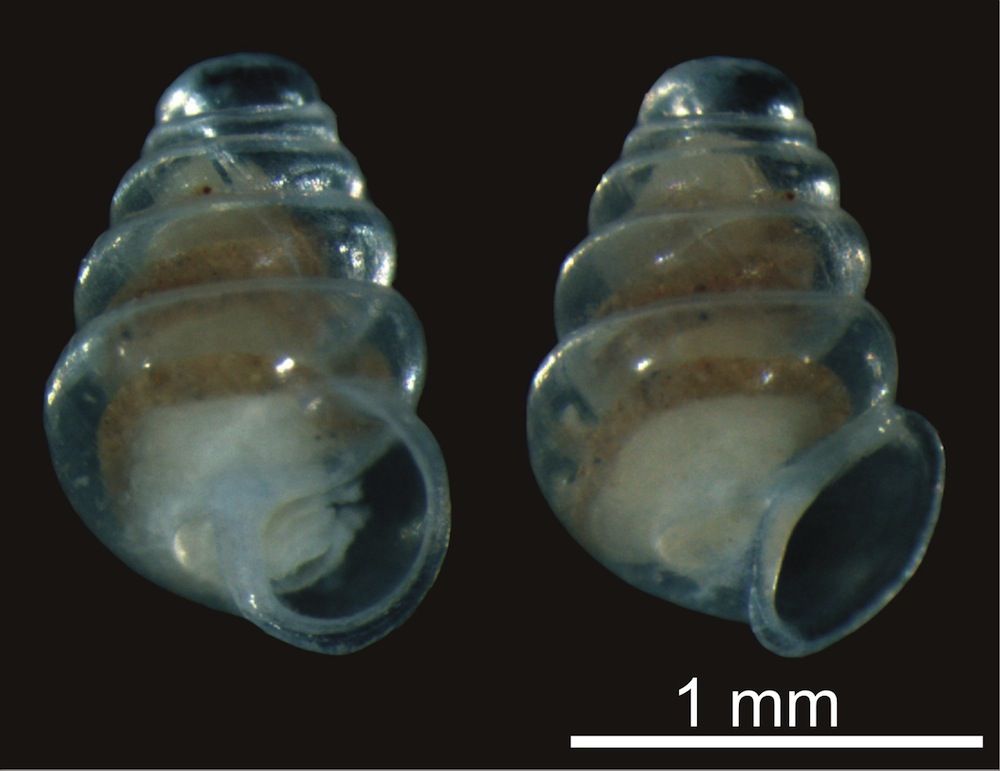

Another top species, the domed land snail, looks like a slow-moving ghost: Its body and shell are see-through. The snail, Zospeum tholussum, lives almost 3,000 feet (914 meters) inside the Earth, in the Lukina Jama-Trojama cave system of Croatia. Pigmentation is unnecessary in this pitch-black habitat; so are eyes, which the snail also lacks. Even for a snail, Z. tholussum is slow. It moves only a few centimeters a week at most, and mostly in circles, Goethe University taxonomist Alexander Weigand told Live Science in September.

Dragons, fairies and giants, oh my

The list of top new species also includes some that seem to come out of a fairy tale. The "mother of dragons" tree (actually known as Keweesak's Dragon Tree) is a gorgeous, 40-foot-tall (12 m) monster found in Thailand. Dracaena kaweesakii grows on limestone in the country's mountainous Loei and Lopburi provinces. The tree has elongated leaves and creamy, white flowers with orange filaments reminiscent of dragon fire.

A world away, but seemingly from the same tale, is Tinkerbella nana, an unbelievably small parasitoid wasp with feathery, delicate wings. The wasp measures only 0.00984 inches (250 micrometers) long and is part of a family called fairyflies. Tinkerbella nana comes from Costa Rica. [5 Alien Parasites and Their Real-World Counterparts]

Rounding out the fairy tale triumvirate is a true giant — at least for a single-celled creature. Spiculosiphon oceana, an amoeboid protist, is between 1.5 and 2 inches (4 to 5 cm) tall, despite consisting of only one cell. The creature scavenges spikey structures from sea sponges and builds a shell out of them, then extends armlike appendages out to feed on tiny invertebrates. S. oceana, like any respectable giant, lives in a cave. The first specimens were discovered off the coast of Spain, in the Mediterranean Sea.

Scientists found another new species, a mysterious microbe, living where it shouldn't have been. Tersicoccus phoenicis was discovered in clean rooms, which are frequently sterilized to prevent microbial life. Electronics and spacecraft parts are manufactured in clean rooms, the latter because scientists would rather not find life on Mars only to learn humans put it there. T. phoenicis resists the temperatures, UV light, hydrogen peroxide and other measures used to scrub clean rooms of their microbes.

Another mini-newcomer is a Penicillium fungus, Penicillium vanoranjei, so named because its colonies are bright orange, and to honor the Dutch Prince of Orange (some of the researchers involved with the identification were Dutch). Researchers found the fungus in soil in Tunisia.

Finally, Australia provides a home for the last new creature on the list, the leaf-tailed gecko (Saltuarius eximius). The new creature lives in the remote, mountainous rainforests of northeastern Australia. It was discovered, along with a new golden skink and a frog that live in boulder fields, during a National Geographic-sponsored expedition. The nocturnal gecko has large eyes and slender limbs, and lurks on rocks and trees during its nighttime hunts.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Most Popular