Who were the Vandals, the 'barbarians' who sacked Rome?

The Vandals sacked Rome and carved out a kingdom in North Africa.

The Vandals were a Germanic people who sacked Rome and founded a kingdom in North Africa that flourished for about a century, until it was conquered by the Byzantine Empire in A.D. 534.

History has not been kind to the Vandals. The word "vandal" has become synonymous with destruction, in part because the texts about them were written mainly by Romans and other non-Vandals.

Despite this modern name association, the Vandals were likely no more violent or destructive than their contemporaries. While the Vandals did sack Rome in A.D. 455, they spared most of the city's inhabitants and didn't burn down its buildings. "Despite the negative connotation their name now carries, the Vandals conducted themselves much better during the sack of Rome than did many other invading barbarians," Torsten Cumberland Jacobsen, a former curator of the Royal Danish Arsenal Museum, wrote in his book "A History of the Vandals" (Westholme Publishing, 2012).

Vandalism

It wasn't until after the French Revolution, in the late 18th century, that the name "Vandals" became widely associated with destruction, Stephen Kershaw, who holds a doctorate in classics, wrote in his book "The Enemies of Rome: The Barbarian Rebellion Against the Roman Empire" (Pegasus Books, 2020).

Kershaw noted that the French abbot Henri Grégoire de Blois used the term "Vandalisme" to describe the destruction of artwork during and after the French Revolution, in reference to the "barbarian" sacking of the "civilized" ancient Rome. The word "vandalism" then became widely used to describe acts of damage and destruction.

Early Vandal history

Around the fourth century A.D. the name "Vandal" tended to be applied to two tribal confederations, the Hasding and Siling Vandals, but in earlier times it likely covered a greater number of tribes under the name 'Vandili,' Jacobsen wrote.

Jacobsen noted that the Vandals may have originated in southern Scandinavia, and that the name Vandal "appears [in historical records] in central Sweden in the parish of Vendel, old Swedish Vaendil."

There are few surviving records of the Vandals' early years. One of the oldest written records of the Vandals comes from the Roman writer Cassius Dio (A.D. 155 to 235). He told of a group of Vandals led by two chiefs named Raüs and Raptus, who made an incursion into Dacia (around modern-day Romania) and eventually made a deal with the Romans to acquire land.

Another writer named Jordanes (a person of Gothic descent who lived in the sixth century A.D.) claimed that in the fourth century A.D., the Vandals controlled a substantial amount of territory north of the Danube River but were defeated by the Goths and sought refuge with the Romans. Today, some scholars believe this claim is untrue. "Recent historians divide roughly fifty-fifty on whether to take Jordanes" word about this defeat and [resettlement in Roman territory]," Walter Goffart, emeritus professor of history at the University of Toronto, wrote in his book "Barbarian Tides: The Migration Age and the Later Roman Empire" (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2006).

Ultimately, evidence of the Vandals' early years in written records remains scarce, and there are also few early archaeological remains to help fill in the record.

"From their first appearance on the Danube frontier in the second century to [their defeat of the Romans in southern Spain] in 422, the Vandals appear only fleetingly within our written sources and leave little or no mark on the archaeological record," Andy Merrills, an associate professor of ancient history at the University of Leicester in the U.K., and Richard Miles, a professor of Roman history and archaeology at the University of Sydney in Australia, wrote in their book "The Vandals" (Wiley, 2014).

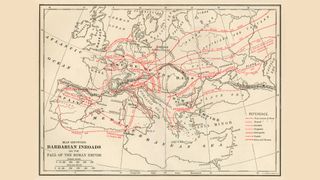

Crossing the Rhine

Around A.D. 375, a people called the Huns arrived north of the Danube from the Eurasian steppe, and they drove a number of other peoples — likely including the Vandals — to migrate toward the Roman Empire. This put a great deal of pressure on the Roman Empire, which by this point was facing frequent crises and had divided into Eastern and Western halves to better control the empire's vast territory.

"In 401, [Roman general] Stilicho, himself of Vandal origins, managed to stop the Vandals' plundering migration through the province of Raetia and engaged them as federates [allies] to settle in the provinces of Vindelica and Noricum," near the Roman frontier in central Europe in an area that now includes parts of Germany and Austria, Jacobsen wrote.

This arrangement soon fell apart. On Dec. 31, 406, a group of Vandals successfully crossed the Rhine river and advanced into the Roman territory of Gaul [what is now France, parts of Belgium and parts of western Germany], and they fought battles against the Franks, another Germanic people. The Franks had already crossed into Roman territory allying with them at times.

Roman inaction and counterattack

At first, the Vandal march into Roman territory did not attract much attention, as the Western Roman emperor Honorius faced more immediate problems: One of his generals had seized control of Britain and part of Gaul and styled himself as Emperor Constantine III.

"Constantine [III's] usurpation, and the invasion of the troops from Britain, was perceived to be a far greater threat to the stability of the empire than the activity of some barbarians to the north," Merrills and Miles wrote.

Amid the chaos engulfing the Western Roman Empire, the Vandals made their way to Iberia (modern-day Spain and Portugal) around A.D. 410. There, the Siling Vandals took over the province of Baetica (south central Spain), while the Hasding Vandals took part of Gallaecia (northwest Spain).

In A.D. 418, the Siling Vandals suffered a defeat at the hands of the Visigoths. The Hasdings were then pushed out of Gallaecia by a Roman army, Goffart wrote.

After these losses, the Vandal survivors united in southern Spain and fought against the Romans again in 422. This time, they won a pivotal victory in a battle near Tarraco (now called Tarragona), a port city in Spain. The victory saved the Vandals from destruction.

The Vandal forces were led or co-led by a man named Gunderic, while a general named Castinus led the Roman forces, who tried to starve the Vandal forces by cutting off their supply lines, Jeroen W.P. Wijnendaele, a senior postdoctoral research fellow at Ghent University in Belgium, wrote in his book "The Last of the Romans: Bonifatius — Warlord and comes Africae" (Bloomsbury, 2015).

At first, this strategy was successful. However, the Visigoths, who had been allied with the Romans, deserted the Roman contingent, reducing the size of the Roman forces. Then, Castinus launched a full-out attack against the Vandals rather than continuing to cut off their supply lines.

The Romans were "soundly beaten" in the assault, and the Vandals "won their first major victory since having crossed the Rhine and were clearly established as the dominant force in southern Spain," Wijnendaele wrote. In the years following their victory, the Vandals consolidated their hold on Spain, capturing Seville after launching two campaigns against the city in 425 and 428, Wijnendaele noted.

Vandal conquest of North Africa

In A.D. 428, a new Vandal leader named Genseric (also spelled Gaiseric or Geiseric) ascended the throne and led the Vandals to North Africa. Under Genseric's rule, which lasted about 50 years, the Vandals took over much of North Africa and established a kingdom there.

This conquest was made easier by Roman infighting. In A.D. 429, the Western Roman Empire was ruled by a child named Valentinian III, who depended on his mother, Galla Placidia, for advice. A Roman general named Aetius had her ear and conspired against the governor of North Africa, a powerful rival named Bonifatius (also spelled Bonifacius). This resulted in Bonifatius being deemed an enemy of the Western Roman Empire.

By the time the Vandals invaded North Africa, Bonifatius' forces had already beaten off two attacks launched by the Western Roman Empire, Wijnendaele wrote.

Some ancient writers claimed that Bonifatius invited the Vandals into North Africa to fight on his behalf against the Western Roman Empire. However, Wijnendaele noted that the ancient writers who made that claim lived at least a century after the events took place, while the ancient writers who lived in Africa around the time of the invasion made no such claim.

Regardless of whether Bonifatius invited them, the Vandals scarcely needed an invitation. North Africa, at that time, was a wealthy area that provided Rome with much of its grain.

The Vandals advanced quickly into North Africa and laid siege to the city of Hippo Regius (modern-day Annaba, Algeria) in A.D. 430. Wijnendaele noted that even in the best-case scenario, Bonifatius' troops would have been outnumbered 3 to 1.

The Vandals laid siege to Hippo Regius for over a year but were unable to take the city, and they were eventually forced to withdraw. Procopius, a writer who lived in the sixth century, wrote that the Vandals "were unable to secure Hippo Regius either by force or by surrender, and since at the same time they were being pressed by hunger, they raised the siege" (translation by Wijnendaele).

Reinforcements from the Eastern Roman Empire arrived and, with Bonifatius' forces, directly attacked the withdrawing Vandal force. The attack was a disaster for the Romans. "A fierce battle was fought in which they were badly beaten by the enemy, and they made haste to flee as each one could," Procopius wrote. After this defeat, the Romans abandoned Hippo Regius, and the Vandals sacked the city.

In A.D. 435, the Romans signed a peace treaty in which they ceded part of North Africa — what is now Morocco and Algeria— to the Vandals. But in A.D. 439, the Vandals broke the treaty and captured the city of Carthage (modern-day Tunis, Tunisia), before advancing into Sicily.

As the Vandals took over territory in North Africa, they persecuted members of the Catholic clergy. The Vandals followed a different type of Christianity, known as Arianism.

"Arianism was the teaching of the priest Arius [A.D. 250 to 336], who lived in Alexandria, Egypt, in the early fourth century. His main belief was that the Son, Jesus, had been created by his father, God. God was therefore unbegotten and had always existed, and so was superior to the Son. The Holy Spirit had been created by Jesus under the auspices of the Father, and so was subservient to them both," Jacobsen wrote. The Catholic belief (the Trinity) is somewhat different, holding that God is present in the Father, Son and Holy Spirit, making them one and equal.

These differing beliefs set the Vandals apart from the Romans, which led to the Vandals persecuting Roman clergy and the Romans condemning the Vandals as heretics.

Vandal sack of Rome

At its height, the Vandal kingdom encompassed an area of North Africa along the Mediterranean coast in modern-day Tunisia and Algeria, as well as numerous islands that included Sicily, Sardinia, Corsica, Malta, Mallorca and Ibiza. This gave them control of much of Rome's grain supply.

The Vandal king Genseric had become extremely powerful and influential by A.D. 455, and his son, Huneric, was set to marry a Roman princess named Eudocia. When Valentinian III, who had by that point reached adulthood, was murdered in that year, Eudocia was pledged to another man. In response to this offense, the enraged Genseric moved his forces toward Rome.

The Romans were powerless to stop him. According to one tradition, the Romans didn't even bother to send out an army but instead sent Pope Leo I out to reason with Genseric. Whether this really happened is unknown, but the Vandals were allowed to enter Rome and plunder it unopposed, so long as they avoided killing the inhabitants and burning down the city.

"For fourteen days, the Vandals slowly and leisurely plunder the city of its wealth. Everything was taken down from the Imperial Palace on the Palatine Hill, and the churches were emptied of their collected treasures," Jacobsen wrote.

"Despite the great indignity of the sack of Rome, it appears that Genseric was true to his word and did not destroy the buildings. Also, we hear nothing of any killings" Jacobsen wrote. However, in some ancient accounts, Genseric captured Romans and took them back to North Africa as slaves.

Following the sacking, the Vandals returned to their kingdom in North Africa. However, North Africa was a key source of grain, and the Romans tried to take it back on several occasions. The emperor Avitus (reign A.D. 455 to 456) launched a campaign against the Vandals that failed, and in response the Vandals cut off Italy's grain supply, Kershaw noted, which fueled civil unrest in Rome. Avitus' successor, Majoran (reign 457 to 461), launched a campaign against the Vandals that also failed, and he was forced to sign a peace treaty with them. The emperor Procopius Anthemius (reign 467 to 472), aided by forces from the Eastern Roman Empire, launched another campaign to take back North Africa that included an armada of 1,100 ships, noted Kershaw. After some initial success, this fleet suffered heavy losses due to the Vandals' use of fireships (ships loaded with flammable materials and set on fire near enemy ships), and ultimately this campaign also failed, and the Romans were forced to sign another peace treaty.

Vandal decline

Genseric died in A.D. 476 and ultimately outlived the Western Roman Empire, which came to an end in A.D. 476 when the last Roman emperor was deposed. "For almost fifty years, he had ruled the Vandals and taken them from a wandering tribe of little significance to masters of a great kingdom in the rich provinces of Roman North Africa," Jacobsen wrote.

However, Genseric's successors faced economic problems, quarrels over succession (Vandal rules stipulated that the eldest male in the family should be king) and conflicts with the Byzantine Empire, the Eastern Roman Empire that was based at Constantinople.

Later Vandal rulers attempted various remedies to fix the kingdom's precarious situation. A Vandal ruler named Thrasamund (died A.D. 523) forged an alliance through marriage with the Ostrogoths, who controlled Italy. Another Vandal ruler named Hilderic (died A.D. 533) tried to improve relations with the Byzantine Empire but was forced out in a revolt.

After Hilderic's death, the Byzantines launched a successful invasion of the Vandals' kingdom, and the last Vandal king, named Gelimer, was captured and taken to Constantinople. Byzantine Emperor Justinian I treated Gelimer with respect and offered to make him a high-ranking nobleman if Gelimer would forgo his Arian Christian beliefs and convert to the Catholic form of Christianity. However, Gelimer declined the offer.

"Refusing the rank of patrician, for which he would have had to abjure his Arian faith, Gelimer was nevertheless invited by Justinian to retire to an estate in Greece — rather a subdued end for the last of the Vandal kings," Merrills and Miles wrote.

Additional resources

- This British Museum blog post written by curator Barry Ager offers a perspective on why the Vandals have such a bad reputation.

- The Metropolitan Museum of Art has an illustrated essay that looks at the "Barbarians" and Rome.

- This paper published in the journal Revue belge de Philologie et d'Histoire (French for "Belgian Review of Philology and History") in 2013 and written by Arbia Hilali, details the importance of North Africa's agriculture for Rome.

Originally published on Live Science on Sept. 29, 2017 and updated on Aug. 30, 2022.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.