Suction is Key to Diving Beetle's Loving Embrace

When it comes to wooing a female, male diving beetles don't have it easy: A male must latch onto his mate underwater, as she wriggles about erratically like a tiny bucking bronco.

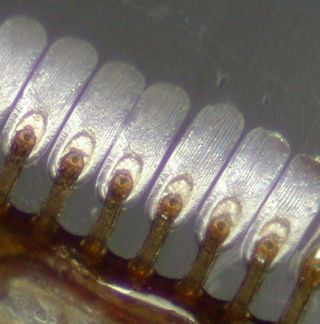

During courtship, male diving beetles (Dytiscidae) use special adhesive hairs, or setae, to keep a grip on the hardened forewings, or elytra, of females. But not all suckers are created equal — circular, suction-cuplike hairs adhere better than spatula-shaped hairs, a new study finds.

The "coevolution of male setae and female elytra has attracted much attention since [Charles] Darwin," the researchers wrote in a study detailed today (June 10) in the Journal of the Royal Society Interface. [Animal Sex: 7 Tales of Naughty Acts in the Wild]

Female beetles have rough surfaces on their forewings, which Darwin thought helped the males to mount them. But more recent research suggests that the rough surface may actually make it harder for the males to stick on.

The continuous evolution of female forewings and male sucker attachments "may instead suggest sexual conflict and an arms race between the two sexes," the researchers wrote.

In the study, researchers from Taiwan compared the underwater attachment ability of different types of male diving beetles: Eretes sticticus,Hydaticus vittatus,Hydaticus pacificus and Cybister rugosus. The first three species have circular suction-cup-shaped hairs, while the latter has spatula-shaped hairs.

Those with spatula hairs have less total contact area to support their body weight while courting a female, so the researchers wanted to know whether these insects could attach to females as well as the ones with suction-cup hairs.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

To measure the amount of attachment force of the different hairs, the researchers collected hairs from the insects and attached them to glass cover slips. They used a sensitive scale to measure the vertical suction force and specialized sensors to measure the horizontal shearing force.

Suction-cup hairs and spatula hairs adhered with about the same force, the researchers found. However, when the researchers took into account body size, the suction-cup hairs provided a better grip on the surface than spatula hairs, and were more resistant to shearing forces like the ones male beetles might experience as females twist and turn.

The findings suggest that suction-cup hairs, which evolved later than spatula hairs, provide a mechanical advantage over spatula hairs. Understanding the insects' suction mechanisms could inspire better man-made underwater attachment devices, the researchers said.

Follow Tanya Lewis on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

A meteorite 100 times bigger than the dinosaur-killing space rock may have nourished early microbial life

380 million-year-old remains of giant fish found in Australia. Its 'living fossil' descendant, the coelacanth, is still alive today.

New memory chip controlled by light and magnets could one day make AI computing less power-hungry