Photos: Ancient Reef Discovered in Namibia

Finding a reef

Researchers have discovered one of the world's oldest aquatic reefs on dry land in southern Namibia. The reef was built about 548 million years ago by the earliest animals known to sport hard shells. [Read full story]

Oldest skeletal animals

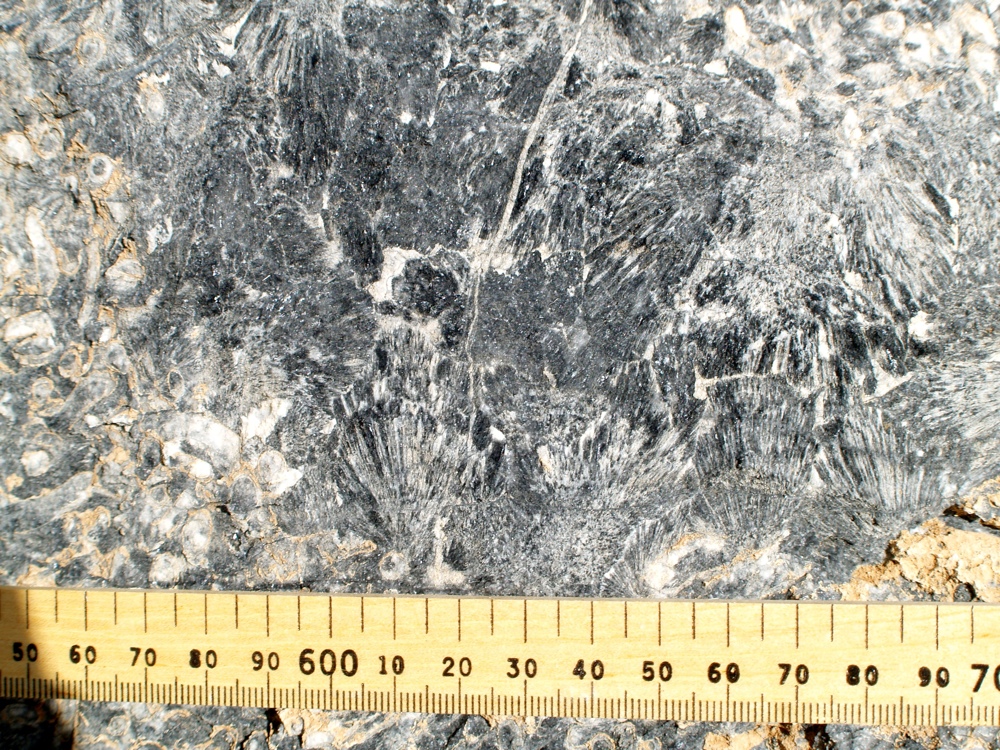

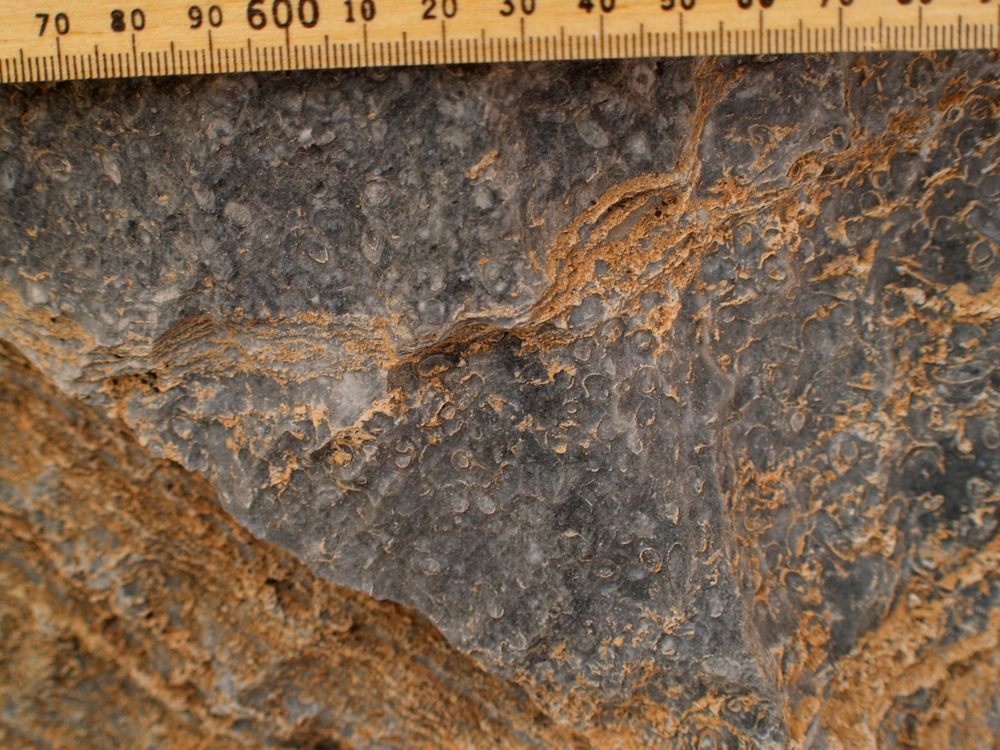

Tiny filter-feeding animals called Cloudina, shown here as tiny white circles, lived on the seabed nearly 550 million years ago during the Ediacaran Period. Fossils of the organisms from what may be the oldest reef, discovered in Namibia, suggest they are the oldest known skeletal animals, as scientists think animals before this time had soft bodies. (The black in the image is the natural cement produced by the Cloudinia creatures.) [Read full story]

Natural cement

And they were reef builders. Some 548 million years ago, organisms in the Cloudina genus (white circles) produced natural calcium carbonate cement (black), which they used to attach themselves to fixed surfaces, and to one another. [Read full story]

Microbial substrate

According to reports, the Cloudinia critters (white circles) may have grown either vertically from or within microbial surfaces (shown here), where the tip of the tube or cone may have served as an attachment site. The white circular shapes on the rock show the fossilized Cloudinia animals, while the surrounding black is the natural cement they exuded long ago.

Early reef building

The researchers' findings imply that metazoans, a group of multicellular animals, had been building reefs millions of years before the Cambrian explosion some 542 million years ago when most of the world's animal phyla seemed to emerge. Shown here, the ancient reef discovered in Namibia, with the reef-building Cloudina animals shown as white circles and their reef-building cement shown in black. [Read full story]

Reef protection

As for why the Cloudina animals developed their ability to build reefs, the scientists suggest the organisms may have needed to protect themselves from predators. The reefs would have provided such protection. In addition, reefs provide access to nutrient-rich currents to help the animals grow in tight spaces where competition for resources was great. [Read full story]

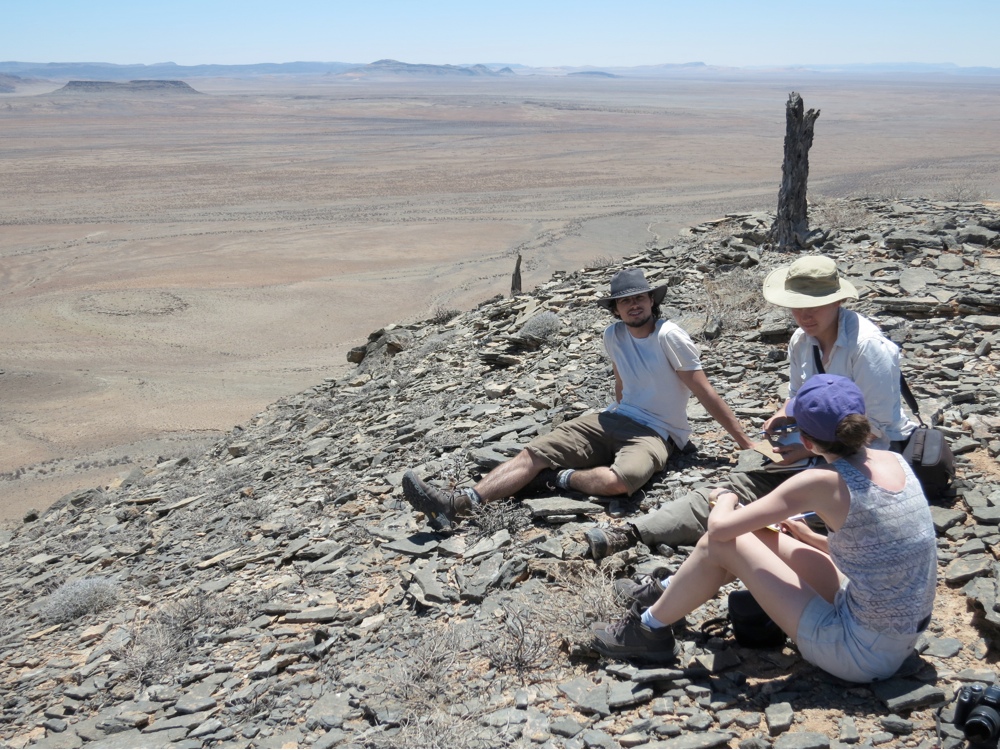

Driedoornvlagte site

The ancient aquatic reef was discovered at the Driedoornvlagte field locality (shown here) in southern Namibia, which long ago was an aquatic ecosystem.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Building reefs

This development of hard shells, which happened through a process called biomineralization, may have triggered a surge in biodiversity in the seas, the researchers said. Here, a fossil from the ancient aquatic reef showing the fossilized Cloudina reef-builders and the natural cement they produced. [Read full story]

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.