From the Frontline: Saving Australia's Threatened Mammals

This article was originally published at The Conversation. The publication contributed the article to Live Science's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

Almost a third of Australia’s mammals have become extinct or are facing extinction, largely thanks to introduced predators such as cats and foxes. But what is the best way to save the species still alive?

In a recent article on The Conversation, John Woinarksi and Peter Harrison wrote that “controlling cats is likely to do more for the conservation of Australia’s biodiversity than any other single action”. But until we find a solution for controlling predators, we have to use more immediate measures.

Islands and fenced reserves — havens free from introduced predators — will play an important role in stemming the seemingly unstoppable flow of Australian mammal extinctions, according to the latest action plan for Australia’s mammals. But reintroduction programs such as these are expensive and don’t always work.

We’ve been trialling reintroductions in central Australia to see if we can improve strategies. Our results were published this week in PLoS ONE.

The last resort

Many of Australia’s mammals once occupied vast areas of the continent. Thanks to the spread of feral predators, many now cling to survival on tiny offshore islands.

These species include the western barred bandicoot, burrowing bettong (or boodie), banded hare wallaby, mala, shark bay mouse and greater stick-nest rat. Introducing these, and other rediscovered species such as bridled nailtail wallaby, to mainland reserves creates important insurance populations and helps restore the functioning of reserve ecosystems.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The NSW government agrees, with plans to protect thousands of hectares with fences in the near future. Within such reserves, it is hoped we can re-establish threatened species to parts of their former ranges through reintroductions.

However, reintroducing a species is not straightforward. Reintroduction programs are expensive, they require ongoing funding and a major criticism is that they frequently fail.

When dealing with critically endangered mammals, the loss of a handful of precious individuals through a failed reintroduction attempt can be a major setback to long-term conservation of the species. Our attempts to reintroduce numbats in 2005 failed due to predators, even though they were released into the fenced reserve.

What’s the best method?

There have been many reviews on how to get reintroductions right. But the conclusions (e.g. whether to use acclimatisation pens or not) are often inconsistent and contradictory. Reintroductions therefore continue to be based on “gut instinct” or precautionary principles, with many choosing to use acclimatisation pens even though they are more expensive and can be stressful to some species.

Some of the strategies for reintroducing mammals include providing food, water, and shelter (often termed “soft” releases), which are thought to improve survival for some species.

Some animals are held in smaller acclimatisation pens at the reintroduction site. This is thought to help them adjust to site conditions and remain in a desired area where additional management measures such as predator control can be implemented.

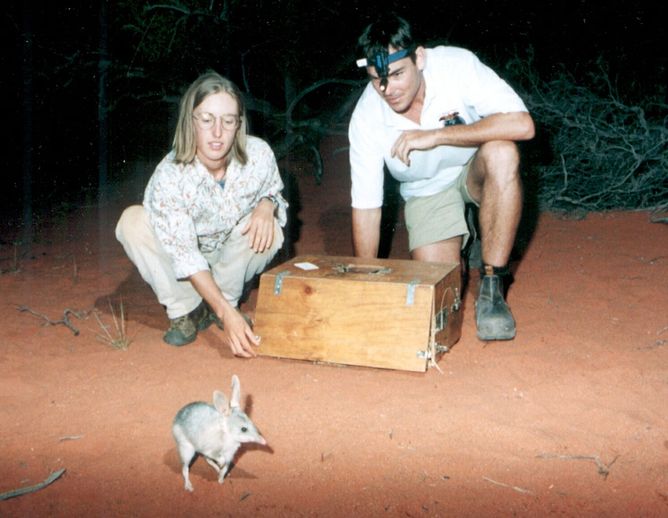

Our research published today trialled reintroductions of greater bilbies, burrowing bettongs and greater stick-nest rats to the Arid Recovery reserve in South Australia. We compared captive and wild animals, delayed releases (animals were first held in acclimatisation pens and assisted with food and shelter), and immediate releases (no assistance was provided).

After their release, we tracked animal movements, observed weight changes, and monitored behaviours to gauge the success of each method.

One size doesn’t fit all

Bettongs, bilbies and stick-nest rats have vastly different behaviours and “life histories” — how animals behave, grow and breed.

We tried two different release strategies on the bettongs and bilbies: holding them in a smaller pen before release, or immediately releasing them into the reintroduction enclosure.

Bilbies are expert diggers and move burrows regularly. The different strategies seemed to have little impact on their weights or how quickly they established burrows.

Bettongs, on the other hand, are sedentary and live in communities that use the same burrow systems over many generations. We found that bettongs that were immediately released lost more weight and took longer to make burrows. They often spent the first days above ground making them more vulnerable to predators.

When it came to the stick-nest rats, which shelter above ground rather than in burrows, we compared the use of captive bred or wild animals. Many of the captive bred animals were killed by predatory birds, because they were naive and chose poorer shelter sites. We found the same problem previously with numbats.

Fenced reserves, island refuges and free ranging reintroductions will remain crucial interim measures to prevent further mammal extinctions. But our research shows there is no “one size fits all” method for reintroducing mammals. The scarcity of these species means that experiments such as ours are uncommon. If we continue to test how different species respond to different methods, we will be able to better plan successful reintroductions in the future.

This article was co-authored by Bridie Hill of the Northern Territory Department of Land Resource Management, and Kylie Piper, CEO/General Manager of Arid Recovery.

The authors do not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article. They also have no relevant affiliations.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article. Follow all of the Expert Voices issues and debates — and become part of the discussion — on Facebook, Twitter and Google +. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This version of the article was originally published on Live Science.