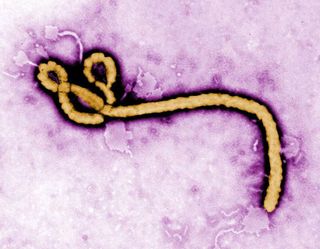

Could Ebola Spread to the United States?

The current outbreak of Ebola in West Africa is now the largest in history, but how likely is it to spread to the United States or other countries around the world?

It's theoretically possible that people with Ebola could travel to other countries on planes, and infect others outside the region. However, it's extremely unlikely that the virus would then cause further outbreaks in communities in the United States or other developed countries with systems in place to contain such deadly infections, experts say.

So far, the Ebola outbreak, which first appeared in December 2013, has infected at least 600 people in Guinea, Sierra Leone and Liberia, including 338 who died, according to the World Health Organization.

The medical group Doctors Without Borders has said the epidemic is "out of control" in the region, and that they do not have the resources to care for the growing number of people who are sick.

Could Ebola come to the U.S.?

One reason why the Ebola virus's spread is possible in theory is that it can take up to 21 days for an infected person to show symptoms. That's ample time for someone with Ebola to travel a long distance by plane and arrive in the United States or Europe, said Derek Gatherer, a researcher at Lancaster University in the United Kingdom who studies virus genetics and evolution. [5 Things You Should Know About Ebola]

But if an infected person arrived in the United States and showed symptoms, doctors would be quick to suspect Ebola based on the patient's travel history, and isolate the patient, Gatherer said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Western medical services would probably cope quite well with catching Ebola as it arrived, because we'd be aware of people coming from Ebola-affected areas," Gatherer said.

Dr. William Schaffner, a professor of preventive medicine and infectious diseases at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tennessee, agreed. Health officials do not think that there is a risk of sustained spread of Ebola in the United States, he said.

"Ebola is not going to come to the United States and become embedded in the United States," Schaffner said.

That's because Ebola's transmission requires close contact with bodily fluids, such as blood or secretions, Schaffner said. "It's really intimate, hands-on contact and involvement with the sick person's body fluids" that spreads the disease, Schaffner said. "Being in the same room with a person in and of itself is not hazardous."

It's possible that a small cluster of cases could occur in a hospital setting in the United States, because healthcare workers have this type of close contact with their patients, but control procedures would prevent further spread, Schaffner said.

The spread of Ebola outbreaks in African countries is sometimes fueled by long-held social customs surrounding human burials, Schaffner said. Those customs include washing the bodies of the deceased. But this would not be a factor in countries, like the United States, that don't have such traditions, he said.

Another important factor limiting the spread of Ebola is that people are not contagious until they show symptoms, Gatherer said. "By the time people are shedding the virus, they're already feverish," making it possible, for example, to screen people with fevers before they get on a plane, Gatherer said. In addition, a person sick with a fever from Ebola is unlikely to feel well enough go out and interact with others, Gatherer said.

What's worrying health officials

Researchers say the virus causing the current outbreak does not appear to be more contagious than those behind previous Ebola outbreaks.

"It's the same species of Ebola that has caused some of the larger and more prominent outbreaks in central Africa," said Thomas Geisbert, a virologist at the University of Texas Medical Branch in Galveston. This species is called Zaire ebolavirus. "It's a slightly different strain, but I haven't seen any data suggesting that it's more transmissible," Geisbert said. Still, only a small dose of the virus is required to cause infection, Geisbert said.

Gatherer noted that it has been six months since the first case of Ebola in the current outbreak was reported in Guinea. And yet the vast majority of cases have remained in an area near the borders of the three African countries.

"Two-thirds of all the cases are still within the narrow geographic region where the outbreak began," Gatherer said.

Health officials are mainly concerned for people living in the areas affected by the outbreak, and they are worried because they have not been able to reduce the number of new Ebola cases as they have in the past, Gatherer said.

WHO is organizing a meeting next week to discuss response to the outbreak and how it can be contained, the organization said.

Live Science staff writer Tia Ghose contributed reporting to this story.

Follow Rachael Rettner @RachaelRettner. FollowLive Science @livescience, Facebook&Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.