Editor's Note: This story was updated at 3:40 p.m. E.T.

A tiny, unassuming little alga may hold the secret to how the sexes evolved.

A single gene that determines male or female sex in multicellular algae evolved from a more primitive version found in a single-celled ancestor that doesn't have sexes, according to a new study.

The new discovery could point to one of the key genetic steps involved in the origin of the sexes.

A good idea

Sex seems to be a good idea, evolutionarily speaking: It has evolved separately in many different life forms, from plants to animals to algae. Many scientists thought the sexes in multicellular organisms originated from two different "mating types" of unicellular organisms, said study co-author James Umen, an evolutionary biologist at the Donald Danforth Plant Science Center in St. Louis.

"Single-cell organisms have sex, too," Umen told Live Science "They do it when cells of two different mating types, but of the same species, fuse."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The idea was tricky to prove. Animals and plants have been having sex, with distinct male and female sexes, for between 500 million and 1 billion years, so the traces of that first step are long gone.

"Our unicellular ancestors that also engaged in sex are so distant from us that a lot of what's happened in between has been erased or changed," Umen said.

Sex change

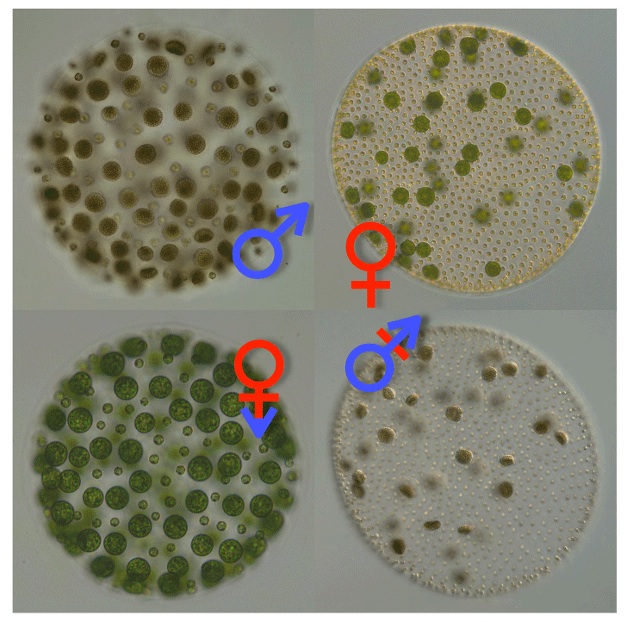

But the multicellular algae Volvox carteri evolved sexes from a more-primitive, single-celled ancestor, Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, in just the past few hundred million years, an evolutionary flash in the pan. As a result, V. carteri and C. reinhardtii have preserved more changes that led to sex differentiation. [Image Gallery: Stunning Dual-Sex Animals]

The team focused on a single gene, dubbed MID, which is present in the "plus" mating type of the single-celled C. reinhardtii but absent in the "minus" mating type. In the multicellular V. carteri, males have their own version of the MID gene, whereas females don't.

The two versions of the MID gene were very similar in both species. Based on the differences in the gene sequence (or the sequence of letters that makes up the gene), the team concluded that the MID gene in V. carteri evolved from the one in C. reinhardtii.

Next, the team inserted the MID gene into female V. carteri organisms. With that one insertion, the females' eggs turned into sperm packets. Meanwhile, reducing the expression of the gene in males turned their sperm packets into eggs.

"By manipulating this one gene we can essentially give Volvox a sex change," Umen said.

Bigger changes

The findings suggest that the first step in the evolution of the sexes may have started with a small change in a mating-type gene. This gene in essence acts like a "master switch" that regulates the genes associated with sex differentiation, Umen said.

But just a handful of genes differ between plus and minus mating-type algae. That's a far cry from what occurs in multicellular algae, in which the genetic master switch controls many genes to make sperm or eggs, Umen said.

So to follow up, the team hopes to unravel how more and more genes came under the control of this sex-determining switch in Volvox, he said.

The findings were published today (July 8) in the journal PLOS Biology.

Editor's Note: This story was updated to correct James Umen's research affiliation.

Follow Tia Ghose on Twitter and Google+. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Tia is the editor-in-chief (premium) and was formerly managing editor and senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com, Science News and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.