Citizen Science Aims to Clean Up Pacific Plastics

This Behind the Scenes article was provided to LiveScience in partnership with the National Science Foundation.

In the classic 1967 movie, The Graduate, a newly minted college graduate played by Dustin Hoffman is told by an older friend that the future would be guided by "one word: plastics." Although the older man's prediction did not refer to the future of marine ecology, the state of the world's oceans has, ironically, borne it out.

Most recently, footage of the Japanese tsunami of 2011 and the search for Malaysia Airlines Flight 370 have vividly underscored the deterioration of some of the world's most remote seas, showing them to be veritable garbage soups, awash in chunks of junk including metals, glass, rubber, medical waste, fishing gear, but most of all, plastics.

Plastic debris of all sizes, including bottles, cups, bags, toothbrushes and grain-sized pieces, represents from 60 to 80 percent of the world's total marine debris, according to the EPA.

Garbage in; Garbage Out

Marine garbage comes from many sources, including galley waste and other trash from ships, recreational boaters, fishermen and offshore oil and gas facilities; boxes and merchandise from large containers ships; rivers that carry storm water-runoff and other waste; poorly maintained landfills; and beach litter.

Studies show that marine plastic harms 267 species worldwide, including species of sea turtles, seabirds and marine mammals — some of which are endangered. Animals are most likely to be hurt by marine garbage after becoming entangled in it or by mistaking it for prey and eating it. For example, sea turtles commonly eat indigestible, potentially gut-clogging plastic objects because these objects look so much like one of their favorite foods: jellyfish.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Another problem: unsightly beached marine debris that washes ashore may discourage income-generating tourism in coastal communities.

The Great Pacific Garbage Patch

Due to varied oceanic and atmospheric forces, marine garbage is concentrated in five major gyres in the world's oceans. One of these is the North Pacific gyre — commonly called the Great Pacific Garbage Patch — which occupies most of the northern Pacific Ocean, an area of about 10 million square miles. One study suggests that the total mass of plastic in the Great Pacific Garbage Patch is six times that of plankton! Debris from the patch commonly washes up on beaches in Hawaii, along the Pacific Northwest coast and in Alaska.

Citizen Scientists Pitch In

In light of the sheer physical enormity of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch and the complexity of its causes, what can we possibility do about it?

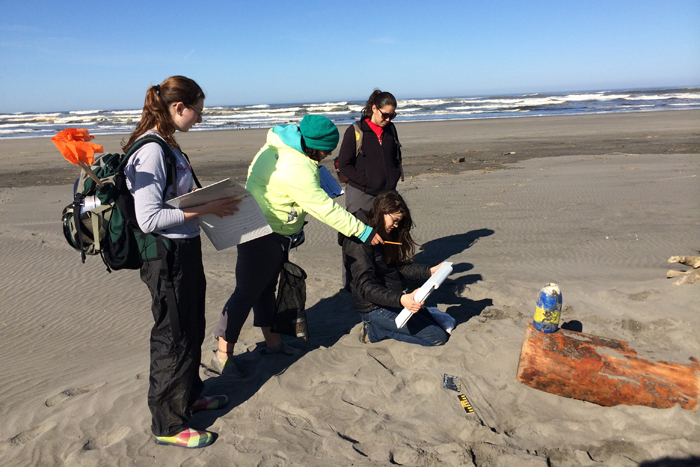

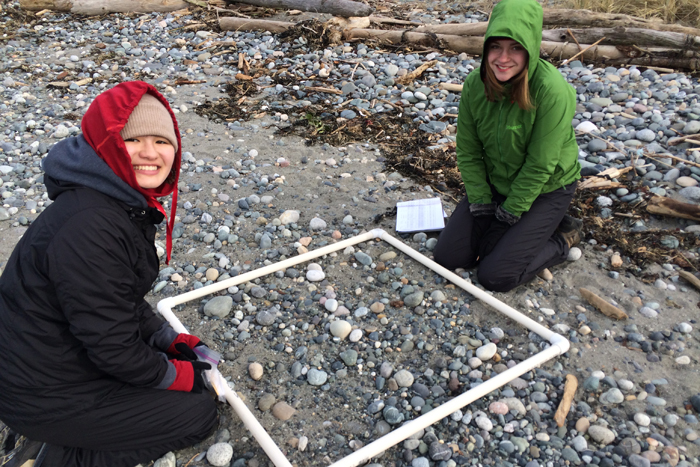

Perhaps help protect some vulnerable populations of wildlife from marine garbage in coastal regions, according to the Coastal Observation and Seabird Survey Team (COASST) — a citizen science group that monitors marine resources and ecosystem health at more than 350 beaches from northern California to Alaska. Although COASST, which receives funding from the National Science Foundation, has long focused on collecting data on beach-cast seabird carcasses as an indicator of coastal health, the group will soon also focus on collecting data on beached marine debris. Resulting data could be used to help support efforts to reduce the impacts of marine debris on coastal wildlife.

Identifying Vulnerable Beaches

Here's how COASST's marine debris program would work: on a monthly basis, COAAST volunteers would collect data on the locations and characteristics of beached marine debris. Debris data could be intersected with information about the location and abundance of coastal wildlife. Resulting analyses could be used to help prioritize the where, when and what of beach cleanups.

For example, suppose scientists identified as a particular threat the potential for seals to become entangled in marine debris with “loops" — discarded plastic holders for six packs, packing straps, boat line and fishing nets or anything else a seal could stick its head through. Volunteers could sift through the COASST marine debris database to identify the locations of large concentrations of "loopy" debris during periods when seals are also abundant.

Kicking off the new COASST program

COASST is currently rigorously pilot testing its new marine debris program. The group plans to start recruiting into this new program volunteers from northern California to the Alaskan coast in spring 2015.

Watch the accompanying video TKTK

Learn more about marine garbage and how it is being addressed by COAAST in the accompanying video, Talking Trash.

The growing power of citizen science

The increasing importance of citizen science to scientific advancement and the many and varied citizen science programs supported by National Science Foundation are discussed in an article, Novel Answer to That Perennial "Earth Day" Question: "What Can I Do to Help?"

Editor's Note: The researchers depicted in Behind the Scenes articles have been supported by the National Science Foundation, the federal agency charged with funding basic research and education across all fields of science and engineering. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation. See the Behind the Scenes Archive.