Twilight Zone: Glow-in-the-Dark Sharks Need Special Eyes to See

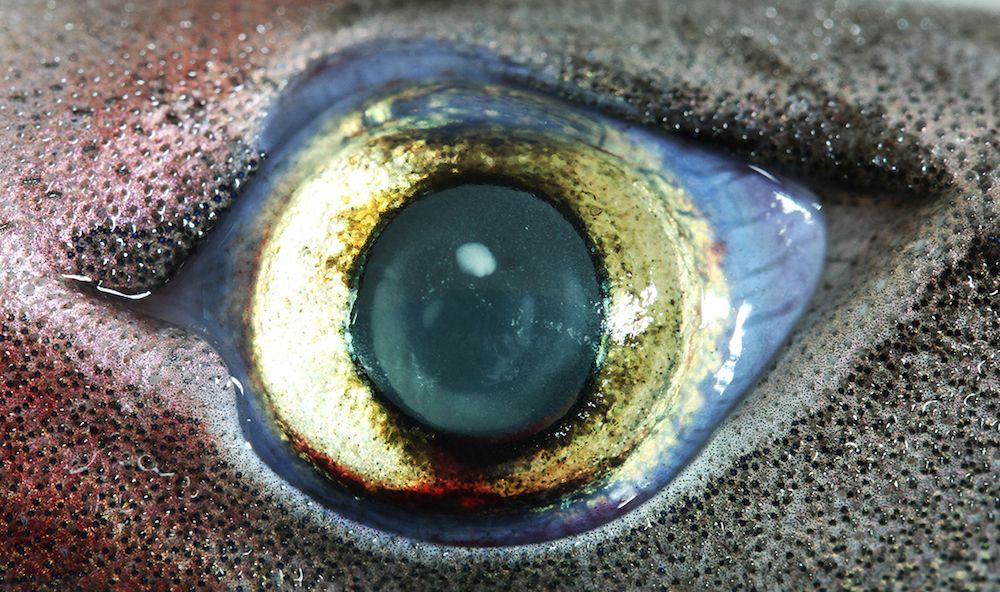

In the "twilight zone" of the deep ocean, strange glowing sharks have evolved eyes that are adapted to see complex patterns of light in the dark, new research reveals.

These bioluminescent sharks have a higher density of light-sensitive cells in their retinas, and some species have even developed other visual adaptations that help them see the glimmering lights they use to signal to each other, find prey and camouflage themselves in this region where little light penetrates, according to a study published today (Aug. 6) in the journal PLOS ONE.

"There are about 50 different shark species that are able to produce light — about 10 percent of all currently known sharks," said study researcher Julien Claes, a biologist at the at The Catholic University of Louvain in Belgium. [Photos: See the 7 Weirdest Glow-in-the-Dark Creatures]

The animals live at a depth of about 650 to 3,300 feet (200 to 1,000 meters), a dim region known as the mesopelagic twilight zone, which only weak sunlight can reach.

Claes and his colleagues recently showed that several species of bioluminescent sharks use a very complex mechanism mainly involving hormones, as opposed to the brain signaling chemicals (such as melatonin) used by many glowing bony fishes.

Scientists know that the animals use their own light to camouflage themselves against predators beneath them by blending in with the sunlight from above, Claes told Live Science. He has also found that some species have "light-saber" spines to ward off predators.

In addition to camouflage and protection, the sharks use light to recognize other members of their own species in order to find hunting partners or mates. For example, glowing lantern sharks possess light-producing structures on their sexual organs that help them find each other in the dark, Claes said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In any optical system, whether it's an eye or a camera, there's a trade-off between sensitivity to light and image resolution, Claes said. Most deep-sea animals have vision tuned for light sensitivity, not resolution. So how can the visual system of glowing sharks be both sensitive to the dim lights of the twilight zone and have the resolution to help them recognize the complex patterns of their fellow animals?

To help answer this question, Claes and his colleagues studied the eye shape, structure and mapping of retinal cells of five species of deep-sea bioluminescent sharks — four lantern sharks (Etmopterus lucifer, E. splendidus,E. spinax andTrigonognathus kabeyai)and one kitefin shark (Squaliolus aliae), using a light microscope and other optical instruments. The researchers then compared the eyes of these animals with those of non-bioluminescent sharks.

They found that glowing sharks have a higher density of light-sensitive cells known as rods in their eyes than non-bioluminescent sharks do, which might give these sharks better temporal resolution, or "faster vision." (For example, if a person had slower vision, when they watched a sprinter running, instead of a smooth movement they would only see disjointed snapshots of the race.)

Having faster vision would help the sharks see quickly changing patterns of light, such as the ones they use to interact with one another.

The scientists also found that the eyes of lantern sharks contain a transparent region in the upper socket, which could help the sharks adjust their eyes' illumination and camouflage themselves against the sunlight above. Additionally, the scientists found a gap in the eyes of the lantern sharks between the lens and iris that lets in additional light, a feature not previously known to exist in sharks.

The findings suggest the visual system of these glowing sharks has co-evolved with their ability to produce light, Claes said.

To confirm these ideas about how these visual adaptations help the sharks camouflage, hunt and communicate, the researchers said they will need to study the electrical physiology of the retina, not just its structure.

Follow Tanya Lewis on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Most Popular