Faraway Earthquake Triggered Antarctica Icequakes

Antarctica's ice snapped and popped because of a major earthquake in Maule, Chile, halfway around the world, a new study reports.

Antarctica has been touched by great earthquakes before. In March 2011, Japan's Tohoku tsunami tore off two Manhattan-size icebergs from the Sulzberger Ice Shelf, more than 8,000 miles (13,000 kilometers) south. Sailors also reported a massive Antarctica iceberg-calving event after Chile's 1868 great earthquake.

But this is the first evidence that distant earthquakes can trigger icequakes in Antarctica. Icequakes are seismic tremblings caused by sudden movement within a glacier or ice sheet, such as from a fracturing crevasse. (Anyone who has dropped an ice cube into a glass of water knows ice snaps under stress.) [Listen to Antarctica's Icequakes]

A little crack

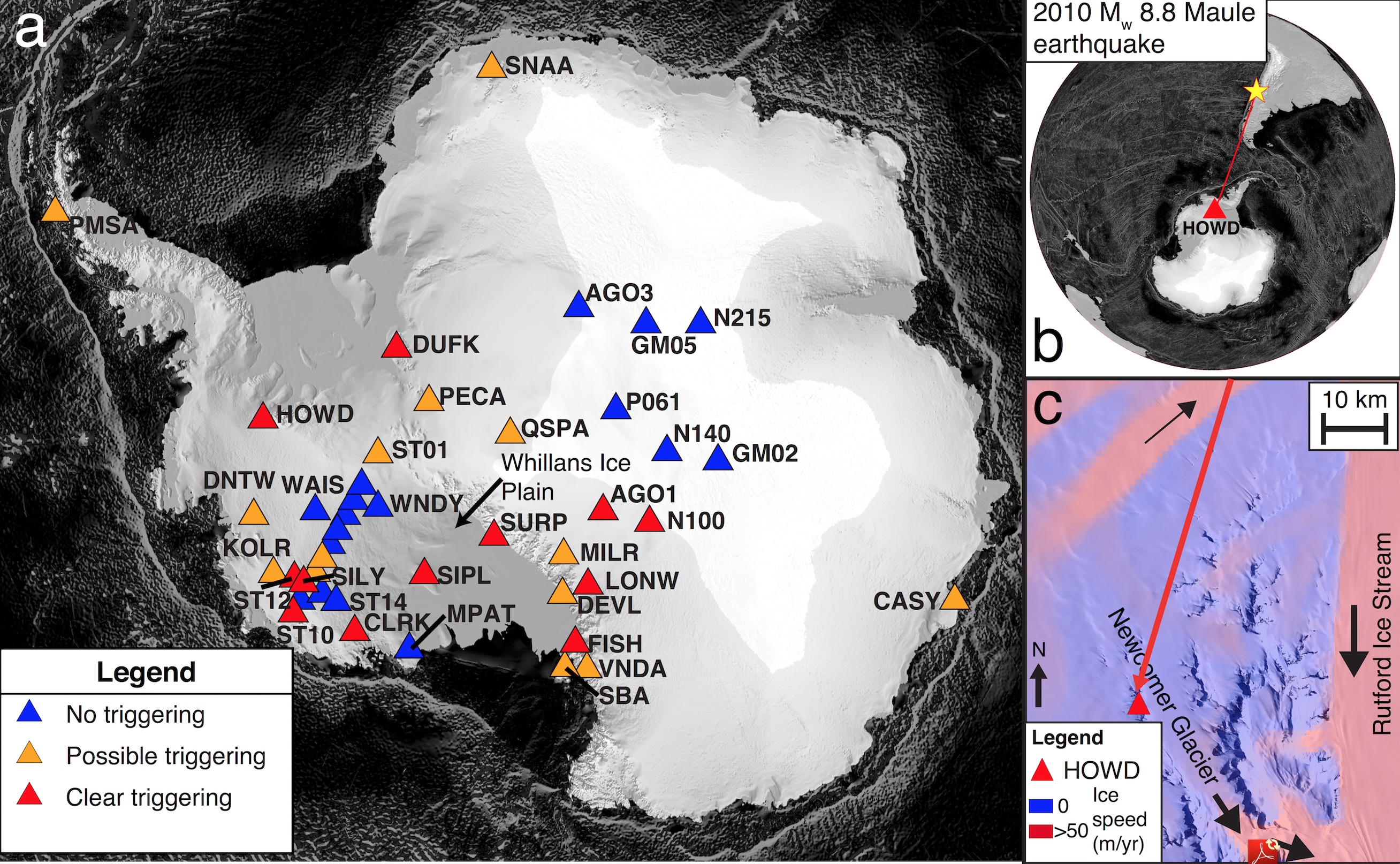

Chile's magnitude-8.8 earthquake on Feb. 27, 2010, set off a flurry of Antarctic icequakes, each lasting from one to 10 seconds, researchers report today (Aug. 10) in the journal Nature Geoscience. The epicenter was 2,900 miles (4,700 km) north of Antarctica.

"Regular icequakes probably occur all the time in Antarctica and other polar regions," said lead study author Zhigang Peng, a seismologist at the Georgia Institute of Technology in Atlanta. "What we found is that they occurred more during the seismic waves of the Maule event."

Many different kinds of icequakes rumble across Antarctica and Greenland. Known icequake triggers include opening and closing of the fractures called crevasses; glaciers tearing away from sticky bedrock; water runoff; and calving, the breaking off of an iceberg. Spooky underwater sounds from melting, cracking icebergs were once called The Bloop.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Only 12 of Antarctica's 42 seismometers picked up icequakes after the Maule earthquake, but the signals seemed to fit a pattern. The pattern suggests that opening or closing of shallow crevasses generated the tiny tremors. For example, seismic stations near Antarctica's mountain ranges and fast-flowing ice rivers known as ice streams were more likely to see icequakes. These are areas with a lot of crevasses. The high-frequency shaking also fits with cracking of brittle ice. [Album: Stunning Photos of Antarctic Ice]

"We think the crevasses are being activated by the surface waves from this big earthquake coming through, and that's making the icequake," said study co-author Jacob Walter, a research scientist at the University of Texas Institute for Geophysics in Austin.

There are also intriguing hints that only crevasses properly aligned toward the incoming seismic surface waves were pinched closed or jacked open, setting off icequakes. However, the evidence is too sparse to test the idea at this time, Walter said.

"For fault zones and tectonic earthquakes, there is a dependence on which direction the wave came from," Walter told Live Science. "We're continuing to work on understanding the phenomenon."

Like a rolling stone

As Walter notes, just one kind of seismic wave, a surface wave, gets the blame for most of Antarctica's icequakes.

A powerful earthquake the size of the Maule quake unleashes strong seismic waves that ripple around the Earth, some of them racing as fast as the speed of sound before tapering off.

The culprit in this case is called a Rayleigh wave. It travels close to the Earth's surface, rolling along like a wave in a lake or the ocean.

The icequake shaking at different stations occurred as the Rayleigh waves traveled across Antarctica, the study reports. (At some stations, there was also a short icequake burst from a seismic "P wave," which travel through the Earth's interior.)

Peng and his colleagues plan to examine the data from older great earthquakes to see if they also spawned icequakes. Walter is also testing whether distant earthquakes may momentarily change the speed of glaciers, by causing them to suddenly unstick and slide.

"It's an interesting result," Walter said. "A big earthquake on the other side of the world can shift things in the Earth and make it crack."

Email Becky Oskin or follow her @beckyoskin. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.