About 600 million years ago, mysterious, frondlike creatures unlike anything found on Earth today filled the primeval seas.

Then, they mysteriously vanished.

Now, new research is shedding light on how these sea creatures, called rangeomorphs, lived and why they went extinct.

The primitive life forms were ideally suited to the nutrient-rich, placid seas of the Ediacaran Period, which lasted from around 635 million to 541 million years ago. But the stationary creatures were no match for the fast swimmers that emerged during the Cambrian Period that followed, and changing seawater chemistry didn't provide the rangeomorphs the nutrients they needed to survive, the researchers found.

"The oceans during the Ediacaran Period were more like a weak soup — full of nutrients such as organic carbon, whereas today suspended food particles are swiftly harvested by a myriad of animals," study co-author Simon Conway Morris, a paleontologist at the University of Cambridge, said in a statement.

Mysterious beings

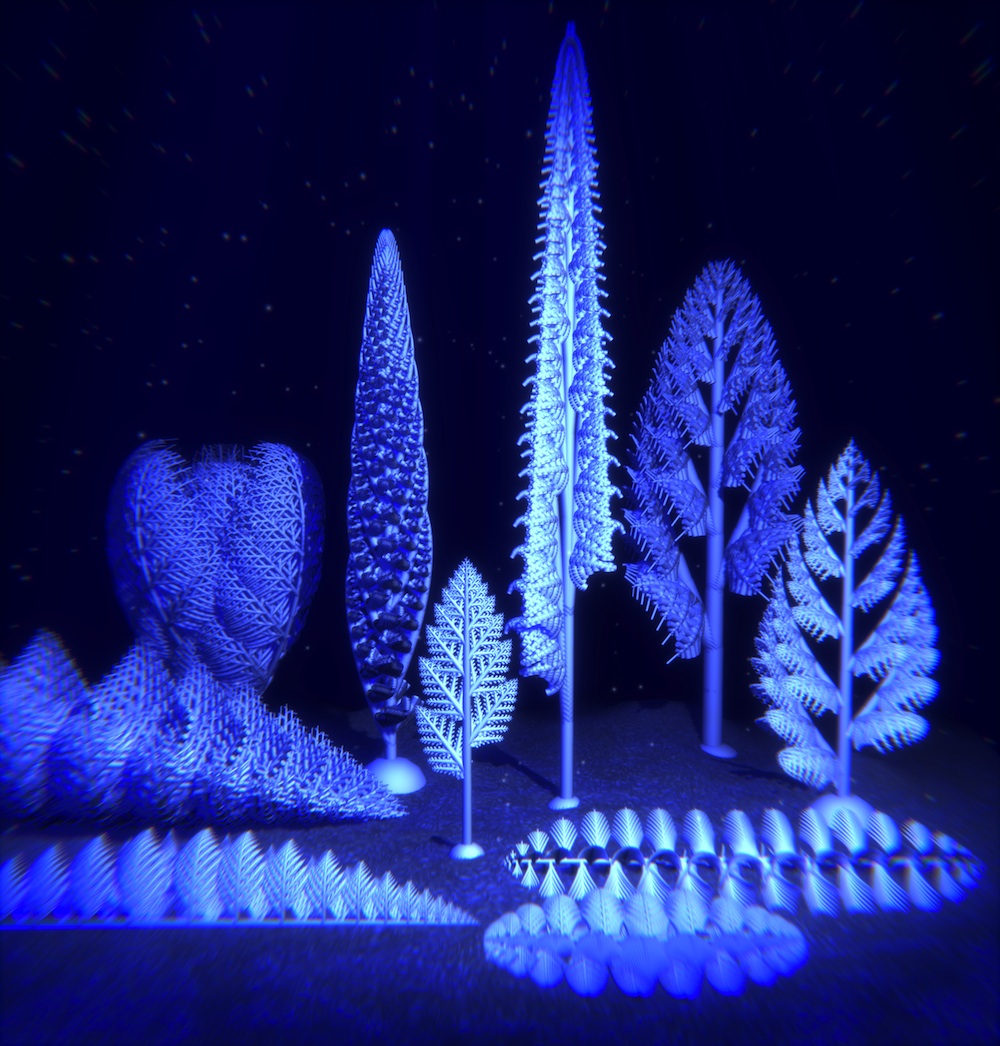

At that time, all life trolled the seas, and most of it was algae or bacteria. But a few larger organisms from that period have left their imprints in rocks around the world. These strange, frondlike creatures, dubbed rangeomorphs, looked a bit like ferns, with fractal branches radiating from a central, stemlike body. Some could be up to 6.5 feet (2 meters) high, though most were closer to 3.9 inches (10 centimeters) in length. During their heyday, they lived everywhere from the shallowest waters to the deepest trenches of the sea and were likely stationary creatures that absorbed nutrients through their body. [See Images of the Bizarre Rangeomorph Animals]

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"We know that rangeomorphs lived too deep in the ocean for them to get their energy through photosynthesis as plants do," study lead author Jennifer Hoyal Cuthill, an earth scientist at the University of Cambridge in England, said in a statement. "It's more likely that they absorbed nutrients directly from the seawater through the surface of their body."

Because the rangeomorphs were radically different from all known life forms, scientists knew almost nothing about how these creatures lived, reproduced or got food. Early on, paleontologists couldn't even agree on whether rangeomorphs were primitive animals similar to sponges, precursors to plants or something from a completely unknown kingdom of life. (They are actually primitive animals.)

Perfect surface area

Around the world, well-preserved fossils have revealed hints of rangeomorphs' 3D structure. Using those fossils as a guide, the researchers developed a 3D computer reconstruction of a rangeomorph's body. The reconstruction revealed that the fractal, or self-similar pattern, of the creatures, was apparent from the very smallest scale of the animal to the largest, according to the study, which was published today (Aug. 11) in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

That, in turn, meant the rangeomorphs maximized their surface area, which made them ideally suited to absorb the dissolved carbon and oxygen from the water column in the peaceful Ediacaran Oceans, about 575 million years ago.

"These creatures were remarkably well-adapted to their environment, as the oceans at the time were high in nutrients and low in competition," said Hoyal Cuthill. "Mathematically speaking, they filled their space in a nearly perfect way."

The rangeomorphs' highly fractal body plans don't resemble those of other enigmatic creatures of the day, such as the leaflike Swartpuntia and the striated, jellyfishlike Dickinsonia, strengthening the notion that rangeomorphs deserve their own clade, the authors wrote in the paper. A clade refers to an evolutionary branch, or one ancestor and all its descendants.

Cambrian extinction

But during the Cambrian explosion, a menagerie of strange and mobile creatures began filling the seas. (The Cambrian explosion refers to an evolutionary period between 520 million and 540 million years ago when exoskeletons, jointed limbs and other innovations emerged.) The new, fast-moving cast of sea organisms quickly snapped up the stationary, defenseless rangeomorphs.

In addition, the water column's changing chemistry no longer provided the rich nutrients the rangeomorphs depended on.

"As the Cambrian began, these Ediacaran specialists could no longer survive, and nothing quite like them has been seen again," Hoyal Cuthill said in a statement.

Follow Tia Ghose on Twitter and Google+. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Tia is the managing editor and was previously a senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.