Brainy Machines Need An Updated IQ Test, Experts Say

For decades, researchers have used the Turing test to evaluate how well a machine can think like a human. But this gauge of artificial intelligence is 60 years old, and is in dire need of an update, experts say.

To develop a replacement, a group of scientists is planning a one-day workshop at the 2015 meeting of the Association for the Advancement of Artificial Intelligence (AAAI) January 25-29 in Austin, Texas.

The new "Turing Championship" will consist of several challenging tasks that assess a machine's performance of humanlike tasks, such as the ability to watch a video and answer questions about it, according to a workshop description obtained by Live Science. [Super-Intelligent Machines: 7 Robotic Futures]

"The idea is to update the Turing test for the modern era, [so that it] drives deep research in a modern way," said Gary Marcus, a psychologist who studies language and music at New York University and co-chairman of the workshop.

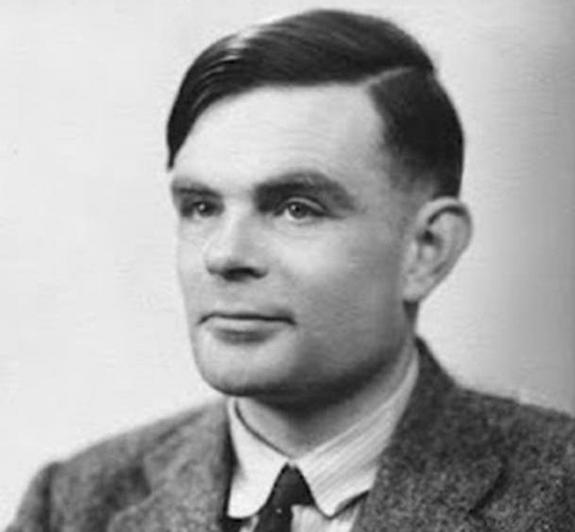

British mathematician and cryptographer Alan Turing introduced the Turing test in 1950 as a way of answering the question of whether machines can think. There are different versions of the test, but its basic format involves a series of brief conversations among human judges, computer programs and other people. A computer program is said to have passed the test if it fools the judges into thinking it is human.

Earlier this year, a Ukrainian chatbot — or conversation progam — named Eugene Goostman made headlines when it supposedly passed a Turing test at the University of Reading in England. But the victory was controversial. The bot had to fool only 30 percent of the judges to pass the test — a low threshold. Also, some said that the chatbot had gamed the system by adopting the personality of 13-year-old boy who spoke English as a second language.

At any rate, many scientists now believe the original Turing test is outdated and overly simplistic. "It's one guy's idea from 60 years ago," Marcus told Live Science. "It has [become] enshrined as if it were magic — it's not," he said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The new Turing test would include more sophisticated challenges, such as the Winograd Schema Challenge proposed by Hector Levesque, a computer scientist at the University of Toronto in Canada. This challenge tests the ability of machines to answer commonsense questions about sentence comprehension.

For example, "The trophy would not fit in the brown suitcase because it was too big. What was too big? Answer 0: the trophy, or Answer 1: the suitcase?" The speech software company Nuance Communications Inc. recently announced it will sponsor an annual competition to solve this challenge.

Another possible Turing challenge is one Marcus himself proposed in an essay published in The New Yorker, involving comprehension of complex materials, including videos, text, photos and podcasts. For example, a computer program might be asked to "watch" a TV show or YouTube video and answer questions about its content, such as "Why did Russia invade Crimea?" or "Why did Walter White [of the TV show "Breaking Bad"] consider taking a hit out on Jessie?"

The workshop organizers have put out a call for papers about creating new Turing test competitions, including ideas about which tests to include, how they should be evaluated and how the competitions should be conducted. The group said it will also accept papers from experienced researchers on what can be learned from existing Turing competitions.

An advisory board for the new Turing Championship includes several leading artificial-intelligence experts, including Guruduth Banavar, a vice president at IBM Research in Yorktown Heights, New York; Oren Etzioni, director of the Allen Institute for Artificial Intelligence in Seattle, Washington; and Leora Morgenstern, senior scientist and technical fellow at Leidos Corporation, a defense company in Reston, Virginia.

Follow Tanya Lewis on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.