'Last Supper' Papyrus May Be One of Oldest Christian Charms

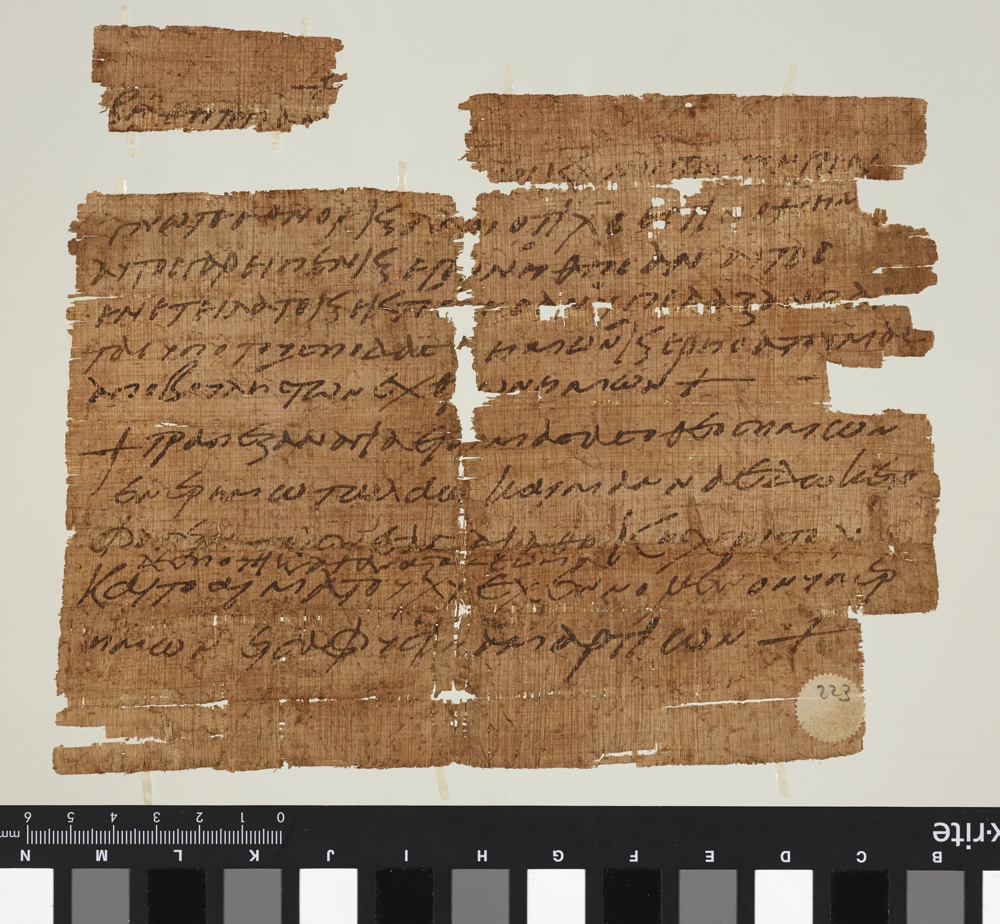

A 1,500-year-old fragment of Greek papyrus with writing that refers to the biblical Last Supper and "manna from heaven" may be one of the oldest Christian amulets, say researchers.

The fragment was likely folded up and worn inside a locket or pendant as a sort of protective charm, according to Roberta Mazza, who spotted the papyrus while looking through thousands of papyri kept in the library vault at the John Rylands Research Institute at the University of Manchester in the United Kingdom.

"This is an important and unexpected discovery as it's one of the first recorded documents to use magic in the Christian context and the first charm ever found to refer to the Eucharist — the Last Supper — as the manna of the Old Testament," Mazza said in a statement. The fragment likely originated in a town in Egypt. [Proof of Jesus Christ? 7 Pieces of Evidence Debated]

The text on the papyrus is a mix of passages from Psalm 78:23-24 and Matthew 26:28-30, among others, said Mazza, who is a research fellow at the institute. "To this day, Christians use passages from the Bible as protective charms so our amulet marks the start of an important trend in Christianity."

The translated text on the papyrus reads:

"Fear you all who rule over the earth.

Know you nations and peoples that Christ is our God.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

For he spoke and they came to being, he commanded and they were created; he put everything under our feet and delivered us from the wish of our enemies.

Our God prepared a sacred table in the desert for the people and gave manna of the new covenant to eat, the Lord's immortal body and the blood of Christ poured for us in remission of sins."

People of the time believed such passages had magical powers, Mazza told Live Science. Supporting that idea, creases can be seen on the fragment, Mazza said, suggesting the papyrus was folded into a rectangular packet measuring 3 by 10.5 centimeters (1.2 by 4.1 inches), and either placed into a box at home or worn around a person's neck.

The amulet was written on the back of a receipt that seems to be for payment of a grain tax. The nearly illegible text refers to a tax collector from the village of Tertembuthis, located in the countryside of Hermoupolis, an ancient city in what is now the Egyptian town of el-Ashmunein.

"The text says that the receipt was released in the village of Tertembuthis. Therefore we may reasonably guess that the person who re-used the back for writing the amulet was from that same village or the region nearby, although we cannot exclude other hypotheses," Mazza told Live Science.

Carbon analysis dates the fragment to between 574 and 660, Mazza said. And while the creator knew the Bible, he or she made plenty of mistakes. "Some words are misspelled and others are in the wrong order," Mazza said in the statement. "This suggests that he was writing by heart rather than copying it."

The discovery, which Mazza presented this week at an international conference on papyri at the university's research institute, reveals that Christians adopted an ancient Egyptian practice of wearing such charms to ward off danger.

"This practice is not very far from nowadays use to wear necklaces with the cross or images of Jesus, Mary, or the saints, for protection," Mazza said. "In many Catholic churches nowadays believers are given holy pictures of the saints with a prayer on the back that you can bring along again for protection."

Mazza will submit a paper on the discovery for publication to Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik.

Follow Jeanna Bryner on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.