Postmortem Photos: King Richard III's Battle Injuries

Laid to rest

A new postmortem analysis of the remains of King Richard III, who died on Aug. 22, 1485 at the Battle of Bosworth Field, reveals the last moments of the English king were quick yet terrifying. Here, the king's body, which was discovered in September 2012 under a parking lot in Leicester, England.Until now, the initial analysis of the king's remains revealed his scoliosis and several battle scars, such as the at least eight wounds found on his skull. [Read full story]

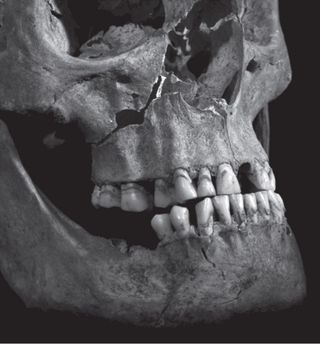

Made by a dagger

The postmortem analysis, detailed in the Sept. 16, 2014, issue of the journal The Lancet, reveals 11 injuries (including nine to the skull) that seem to have occurred around the time of death. Here, a computed tomography (CT) scan of Richard III's jaw shows a linear slash mark 0.4 inches (10 millimeters) long on the right side of the chin, probably made by a sharp-edged dagger. On the ramus (the vertical portion of the jawbone), another wound is visible, this one only 0.2 inches (5 mm) long. [Read full story]

Upper jaw injuries

A photograph of Richard III's jaw and face show penetrating injuries to the maxilla, or upper jaw. The hole seen in the upper jaw is about 0.4 inches (10 mm) in diameter, with a fracture radiating out from either side. Researchers suspect that someone stabbed Richard in the right cheek, creating this wound. The wound would not have been fatal. [Read full story]

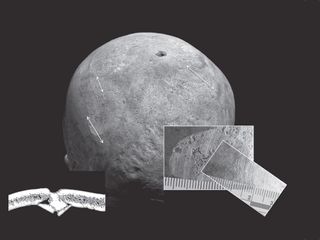

Shaving Injuries

The skull of Richard III sports several "shaving injuries" — though these aren't the type of nicks you get in the bathroom with a shaving razor. The arrows mark spots where a blade sliced through the scalp and across the skull, shaving off small slices of bone. The inset on the right shows the striations made by the blade; these striations are similar enough that researchers strongly suspect that the same weapon made these injuries.

Meanwhile, the hole at the top of the skull measures about 0.4 inches (10 mm) in diameter. The shape of the injury indicates that it was made by a needle-like rondel dagger, probably in a blow delivered from above the king's prone body. The inset to the left shows a CT scan of this rondel dagger injury in cross-section, with jagged flaps of bone intruding into the skull. This injury would have bled heavily but would not have been immediately fatal. [Read full story]

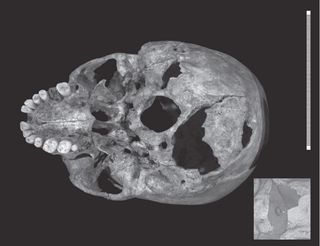

Richard III kneeling

The bottom rear of the skull provides the likely clue to Richard III's death. The round hole in the middle of the skull is the natural opening where the spinal cord and brain meet. To the right and slightly below this natural opening is a huge head wound with a bit of loose skull bone fitted back in to the injury. Directly above the natural opening is a second penetrating wound.

Richard III was likely prone or kneeling when someone standing over him thrust a sword, halberd or other large-bladed weapon into his skull. One of the blows ran right through his brain, scraping the opposite skull bone. Either of these injuries would have been fatal within moments. [Read full story]

Humiliation wound

Richard III would have been wearing armor on the battlefield, perhaps explaining why there are few wounds to his skeleton beyond the skull. Nevertheless, this right tenth rib sports a cut mark, likely made from behind with a fine-edged dagger. Researchers suspect this injury was a "humiliation wound," made after the king was dead and stripped of his armor. [Read full story]

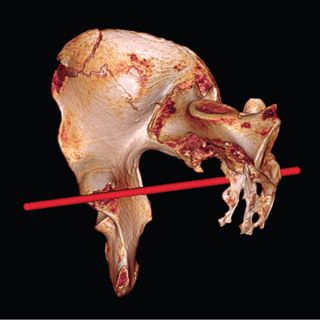

The right buttock

Another likely humiliation wound was found on the pelvic bone. This CT reconstruction shows how a blade could have entered the right buttock, scraping the pelvis as it went. Historical accounts hold that Richard III was slung face-down over a horse and paraded to Leicester after his death; it's likely that his exposed backside made a tempting target for victorious forces.

Though this wound was almost certainly inflicted after death, it would have very likely killed Richard III if he had been alive. The blade would have caused massive internal bleeding in the pelvis and could have penetrated the bowel, spilling deadly bacteria into the abdomen. [Read full story]

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

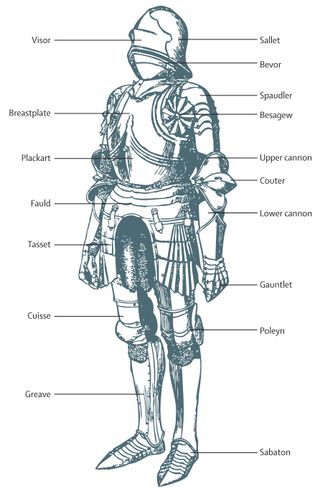

Battle armor

This diagram shows 15th-century battle armor, which would have looked very similar to what Richard III was wearing at the Battle of Bosworth Field. Not all soldiers would have been similarly equipped, but as the king, Richard would have worn the best protection available. However, the wounds to the king's head suggest that he had removed or lost his helmet before or during his final moments. Historical accounts, which match the forensic findings, hold that Richard III had dismounted from his horse, which was mired in mud, and was fighting on foot when he died. [Read full story]

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Most Popular