Are Pro Athletes Prone to Violence?

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Several professional athletes have made the news recently for charges of domestic violence, including athletes in the National Football League and the U.S. women's soccer team. But are elite athletes actually more prone to domestic violence than other people?

It's difficult to know for sure. By some estimates, NFL players have a considerably lower rate of domestic violence arrests than the general population. But because NFL players have high salaries, some argue that their rate of domestic violence arrests should be even lower than it is, because people in high-income groups tend to have very low rates of domestic violence.

In addition to this, another analysis suggest that at the college level, athletes make up a larger share of sexual abuse and violence perpetrators on some campuses than would be expected, given that athletes make up a relatively small percentage of the campus population.

But in any case, experts say a key question remains: how can such cases be prevented?

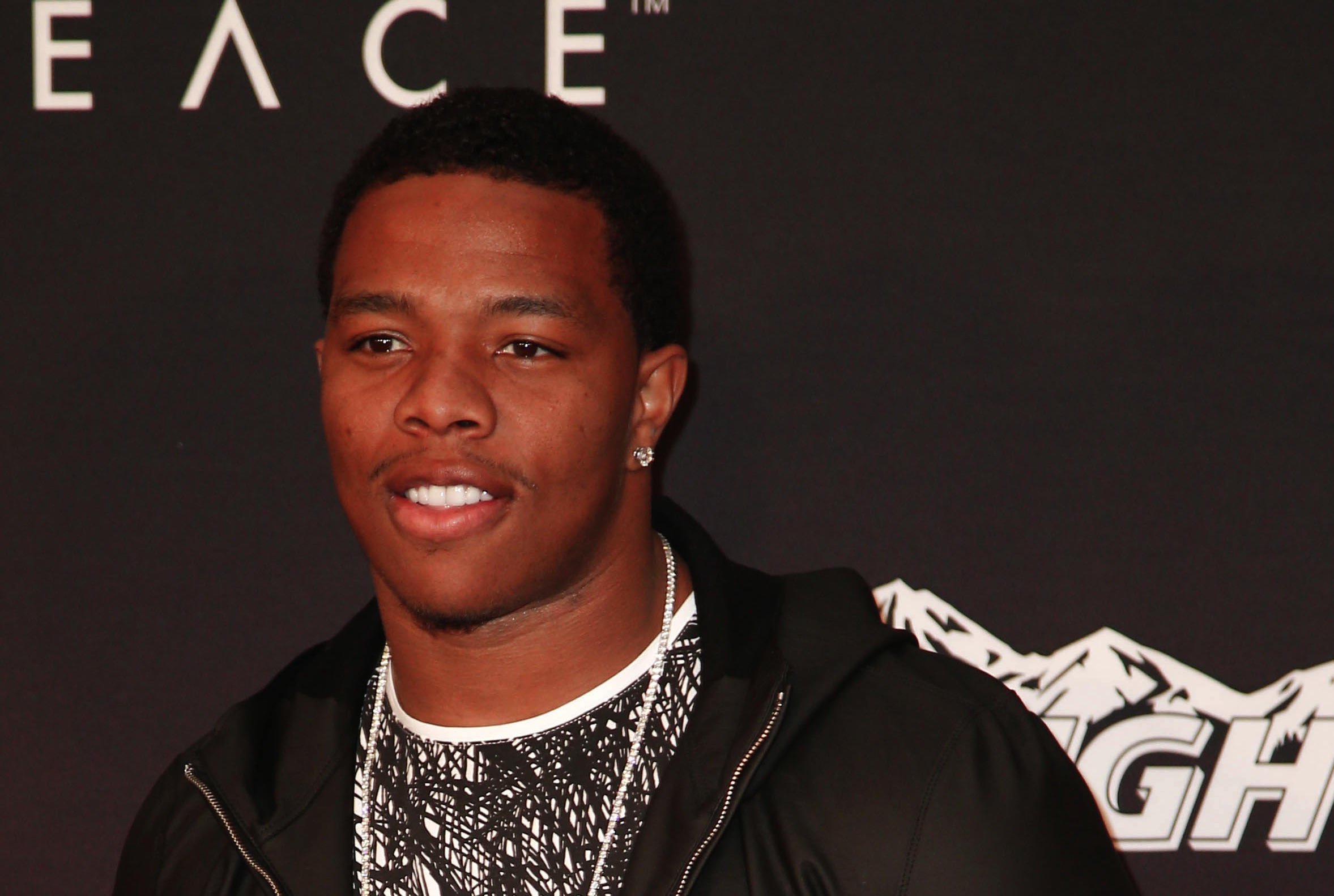

In March, Baltimore Ravens running back Ray Rice was charged with assaulting his fiancée, and this month, a video of the incident that shows Rice punching his fiancée in the face was released by the website TMZ, and led to his suspension from the league.

Also this month, Minnesota Vikings running backAdrian Peterson was charged with child abuse for allegedly hitting his 4-year old son with a tree branch. And U.S. women's soccer player Hope Solo is set to stand trial in November for allegedly punching her sister and her nephew, according to the New York Times.

Although such reports might make it seem that pro athletes are more likely to be perpetrators of domestic violence, this is actually not the case, according to some sources.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"It certainly feels that athletes are more involved than non-athletes [in domestic violence], especially recently," said Mitch Abrams, a sports psychologist and author of "Anger Management in Sport" (Human Kinetics, 2010).

However, "Athletes are not more violent than non-athletes," Abrams told Live Science, but rather "when they do transgress, its big news." [Understanding the 10 Most Destructive Human Behaviors]

According to the website FiveThirtyEight, the overall arrest rate (for any crime) for NFL players is just 13 percent of the national average arrest rate for men ages 25 to 29. When only arrests for domestic violence are considered, NFL players' arrest rate rises, but still remains at half the national average arrest rate. This seems to suggest that these athletes are not especially prone to domestic violence.

However, FiveThirtyEight also notes that people with higher income levels generally tend to have lower rates of arrest for domestic violence. The rate of domestic violence arrest among NFL players is higher than would be expected for their income level, according to FiveThirtyEight, which could suggest that these athletes are indeed more prone to domestic violence.

And other sources also suggest a link exists between elite athletes and such crimes. For example, an analysis of 10 Division I colleges showed that student athletes comprised 3 percent of the college population, but 19 percent of perpetrators of sexual abuse or violence, said Stanley Teitelbaum a sports psychologist in private practice in New Jersey, and author of "Athletes Who Indulge in the Dark Side" (Praeger Press, 2012).

So together, the statistics remain unclear on whether elite athletes are prone to domestic violence. But experts on both sides say there are some sociological factors that may contribute to domestic violence cases among pro athletes.

Abrams said a contributing factor to domestic violence among football players may be that they are desensitized to physical conduct because it's "part of what they do all the time."

Teitelbaum agreed, saying that players can take their aggression with them when they leave the field.

"They're trained to be very aggressive and somewhat violent on the field, that's the nature of the game and that’s how they become important players. And sometimes it's difficult for athletes to turn that off when they go back to their regular lives," Teitelbaum said.

In addition, some players grow up in an environment where violence is used to resolve conflict, Teitelbaum said. "When you grow up, you repeat what you've seen, or what has been done to you," Teitelbaum said. (Peterson has said that he disciplined his son the way he was disciplined as a child.)

Athletes may also, from an early age, be held up on a pedestal, and some may end up feeling entitled to do whatever they want, Teitelbaum said.

But this does not excuse their behavior, Abrams said. "One incident [among players] is too many," Abrams said.

Abrams said severe penalties against players are necessary, but are not enough by themselves to change a person's behavior. "If all you're going to do is have severe penalties, you're not going to see a reduction," in cases of violence, Abrams said.

People who commit violent acts need to undergo treatment to teach them anger management and conflict resolution skills, Abrams said.

In addition to physical violence, there is often a lot of verbal and psychological abuse that goes on in athletes' relationships that does not receive as much attention, Abrams said. Not only can verbal and psychological abuse be harmful in and of themselves, but they also often precede physical violence, and so they also need to be addressed in treatment, Abrams said.

"If we want to attack this problem, we need to teach people about how to be respectful in relationships," Abrams said. "We need to do more to decrease the abuse that happens in relationships — not just the physical abuse, all abuse," he said.

Follow Rachael Rettner @RachaelRettner. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus