Bizarre Sphere Fossils Could Be Among World's Earliest Animals

A series of mysterious spherical fossils found in southern China may be remnants of some of the world's earliest animals.

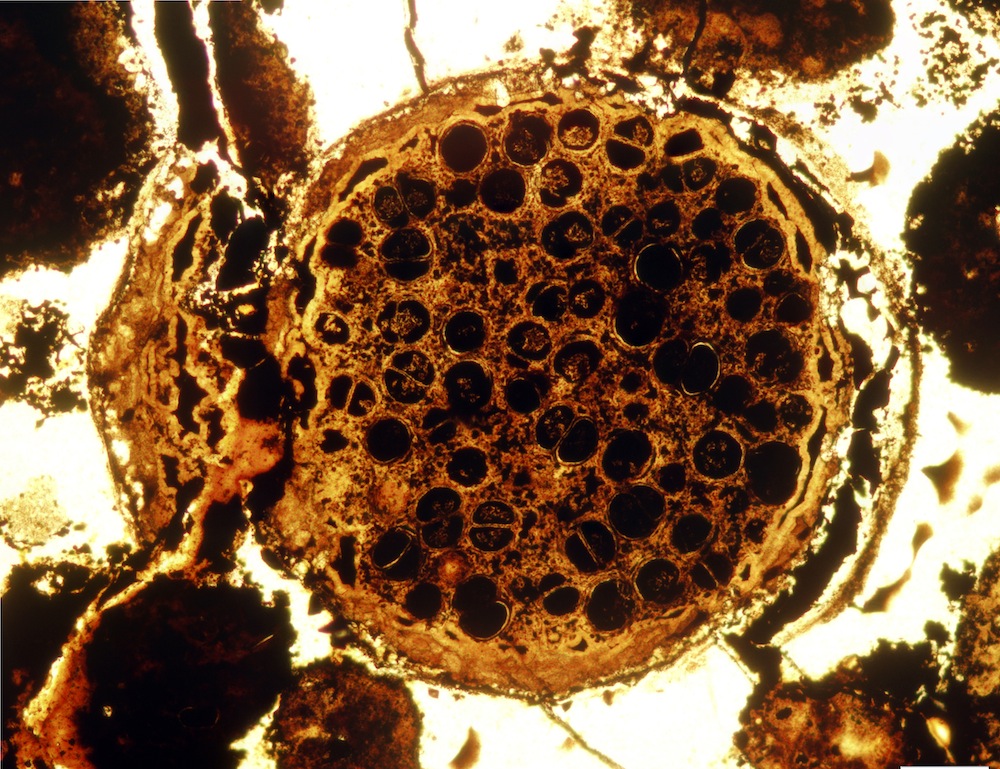

A new study finds that these controversial fossils are not likely to be bacteria or single-celled protists; their cells, preserved for more than 600 million years in rock, are too complex and differentiated. Instead, the fossils may be multicellular algae, or even the embryosof ancient animals.

"The real value of these fossils is that we now have some direct evidence about how this transition from single-celled organisms to things like animals and plants occurred in the evolutionary past," said study researcher Shuhai Xiao, a geobiologist at Virginia Tech in Blacksburg. [See images of the strange spherical fossils]

Multicellular and differentiated

The bizarre fossils, known as Megasphaera, come from a rock layer in southern China called the Doushantuo Formation. Xiao first studied Megasphaera specimens in 1998 and suspected that they might be animal embryos.

Each fossil measures a mere 0.03 inches (0.7 millimeters) or so across and comes from what would have been a shallow marine environment at the time.

But no adult animals that might have produced these embryos have ever been found, leaving the identity of the fossils open to scrutiny. Previous Megasphaera fossils studied have been extracted from a gray rock in the Doushantuo Formation, Xiao told Live Science. Now, he and his team have succeeded in extracting more difficult-to-see fossils from the formation's black rocks.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

By slicing the rocks ultrathin, the researchers were able to shine light through the fossils to see the structures inside, just like stained glass. Using microscopy, they observed multiple cells, cleaved together in spherical clusters. The cells were different from one another in shape and size, suggesting they have developed different tissue types — a process known as cell differentiation — and presumably have different cellular functions, Xiao said.

"That is a telling sign of the complexity of multicellular organisms that you don't find in bacteria or protists," he said.

Among the cells were clusters that contained smaller cells than the rest of the fossil. Because of their nestled appearance, the researchers dubbed these clusters "matryoshkas," after the word for Russian nesting dolls. They suspect the matryoshkas may be reproductive cells.

Animal or plant?

Some of the fossils also have what appears to be a peripheral layer that is different from the interior cells, Xiao said.

"The bottom line is that they are multicelled and that they have cellular differentiation and that they have separation of reproductive cells from sterile somatic [body] cells," Xiao said. "This is a big thing, because if you look at modern multicellular organisms, including animals, this is a critical step towards very complex multicellular organisms."

The fossils may thus represent the transition between single-celled life and multicellular animals, Xiao said. However, their anatomy is also consistent with algal life forms, meaning the fossils could be plantlike instead.

The next step, Xiao said, is to keep looking for more Megasphaera — including the elusive adults that may have produced the possibly embryonic fossils.

"We will have to be open-minded in terms of what can be expected," Xiao said. "From the living animal point of view, we only have a certain morphology to go with. But there are extinct animals or even offshoots of the lineages leading to animals that could be rather different from what we know as animals living today."

The findings were published online today (Sept. 24) in the journal Nature.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.