Observers of Wednesday morning's total lunar eclipse might be able to catch sight of an extremely rare cosmic sight.

On Oct. 8, Interested skywatchers should attempt to see the total eclipse of the moon and the rising sun simultaneously. The little-used name for this effect is called a "selenelion," a phenomenon that celestial geometry says cannot happen.

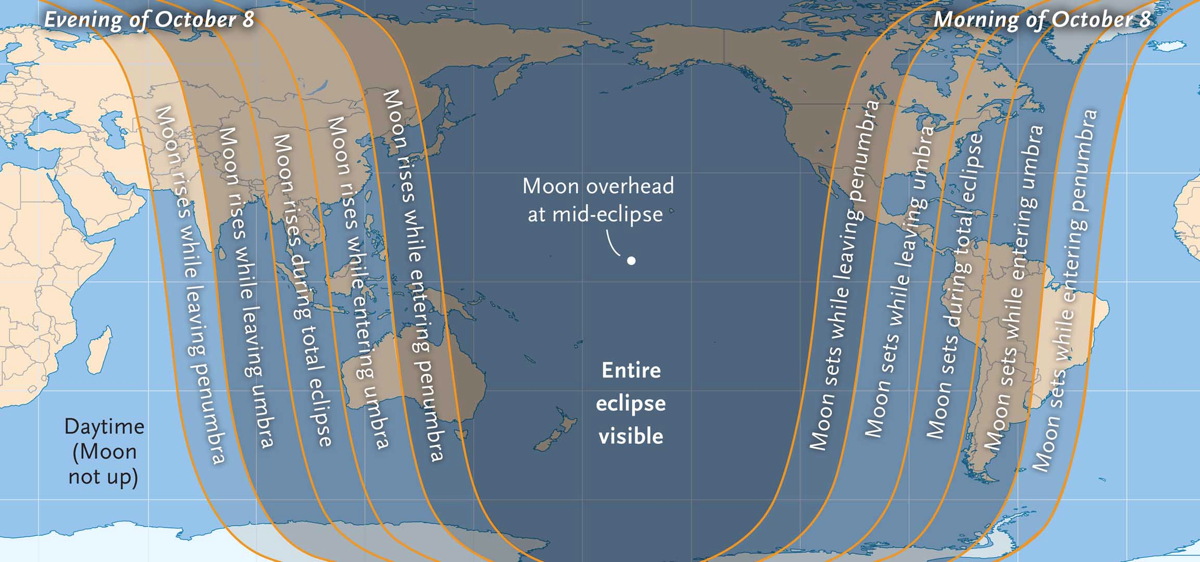

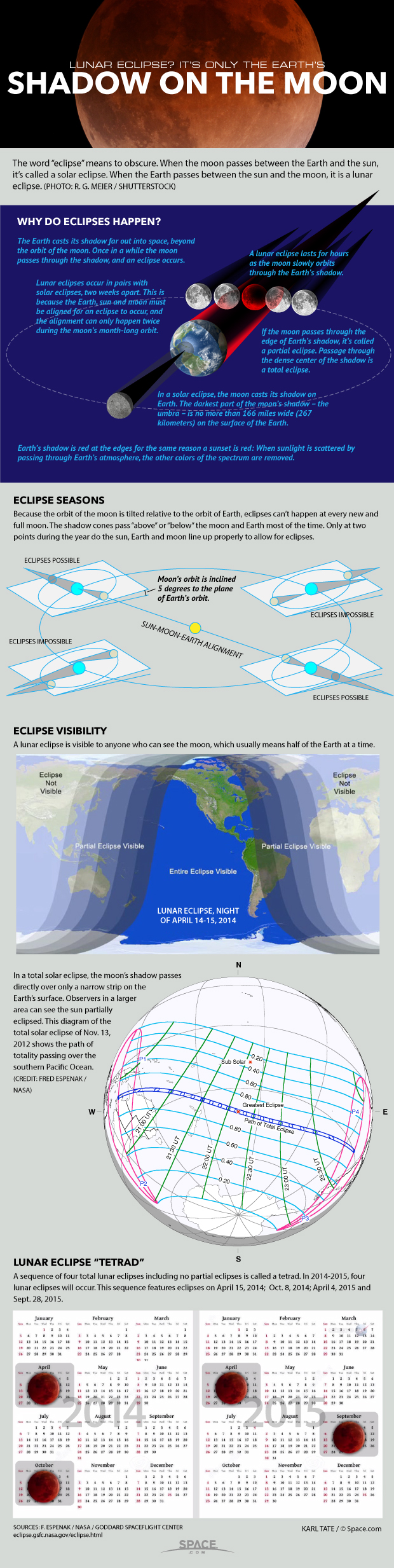

And indeed, during a lunar eclipse, the sun and moon are exactly 180 degrees apart in the sky. In a perfect alignment like this (called a "syzygy"), such an observation would seem impossible. But thanks to Earth's atmosphere, the images of both the sun and moon are apparently lifted above the horizon by atmospheric refraction. This allows people on Earth to see the sun for several extra minutes before it actually has risen and the moon for several extra minutes after it has actually set. [How to See the Total Lunar Eclipse (Visibility Maps)]

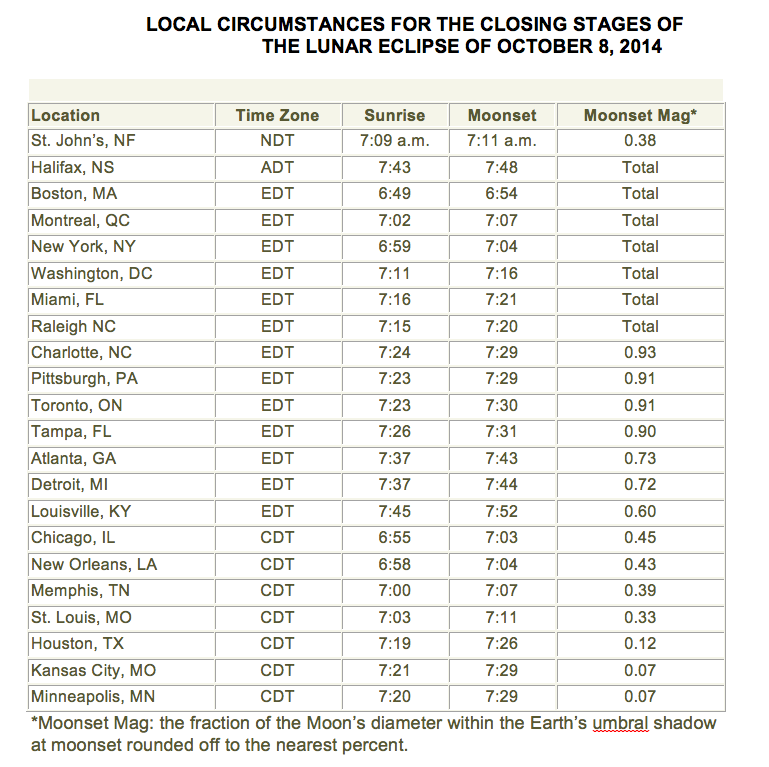

As a consequence of this atmospheric trick, for many localities east of the Mississippi River, watchers will have a chance to observe this unusual sight firsthand. Weather permitting, you could have a short window of roughly 2 to 9 minutes (depending on your location) with the possibility of simultaneously seeing the sun rising in the east while the eclipsed full moon is setting in the west.

Regions of visibility

From Newfoundland, the start of the partial stages of the total eclipse begins about 30 to 45 minutes before moonset.

A growing scallop of darkness will appear on the upper left part of the moon when it sets as the sun is coming up. Across eastern Nova Scotia, only the lowermost portion of the moon will be in view as it drops below the western horizon. Farther to the west and south along the Atlantic seaboard, the moon will rise completely immersed in the Earth's shadow.

Now you see it … now you don't?

Then again, sighting a selenelion might be problematic feat. Twenty-five years ago, in the August 1989 issue of Sky & Telescope, Bradley Schaefer, an astronomer who extensively studied the visibility of the moon when it was low in the sky, noted that the full moon only becomes visible when it is about 2 degrees up and the sun is about 2 degrees below the horizon.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

So, depending on the clarity of your sky, you might have up to roughly 10 to 15 minutes before sunrise for the sky to still be dark enough, and the moon to be high enough above any horizon haze for it to be clearly visible. And keep in mind that this holds only for the uneclipsed portion of the moon. You might, however, be able to mitigate the effects of a brightening sky somewhat by using binoculars or a telescope.

If the moon is totally eclipsed prior to sunrise, you probably are going to have to scan the western horizon with binoculars as the twilight brightens in order to still detect some semblance of the Moon, which will somewhat resemble a very dim and eerily illuminated mottled softball.

A peculiar moonset

People who live in those portions of the United States and Canada that are a few hundred miles inland from the Eastern Seaboard should have a good view of the Moon's emergence from the umbra somewhat later. The low, partially eclipsed Moon in deep-blue twilight should offer a wide variety of interesting scenic possibilities for both artists and astrophotographers. From Toronto and points south through the eastern Ohio Valley and into the Piedmont to the Florida Gulf Coast, a peculiar-looking, waxing crescent moon with its cusps pointing downward will appear to set beyond the western horizon.

Farther west, across the western Great Lakes and down through the Deep South to the Gulf of Mexico, the moon will appear to be notched on its lower right side by the shadow.

Going still farther west, the Moon will go down "full," but if the western horizon is haze-free, assiduous observers from much of Minnesota, western Iowa, eastern portions of Nebraska and Kansas as well as central sections of Oklahoma and Texas might still be able to detect a faint penumbral stain on the moon's lower right limb.

Editor's Note: If you snap an amazing picture of the Oct. 8 total lunar eclipse, you can send photos, comments and your name and location to managing editor Tariq Malik at spacephotos@space.com.

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmer's Almanac and other publications, and he is also an on-camera meteorologist for News 12 Westchester, N.Y. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.