Insect Family Tree Maps 400-Million-Year Evolution

Creating a family tree that dates back more than 400 million years and details the evolution of the most diverse group of animals on the planet is no easy feat, but one ambitious group of scientists has done just that.

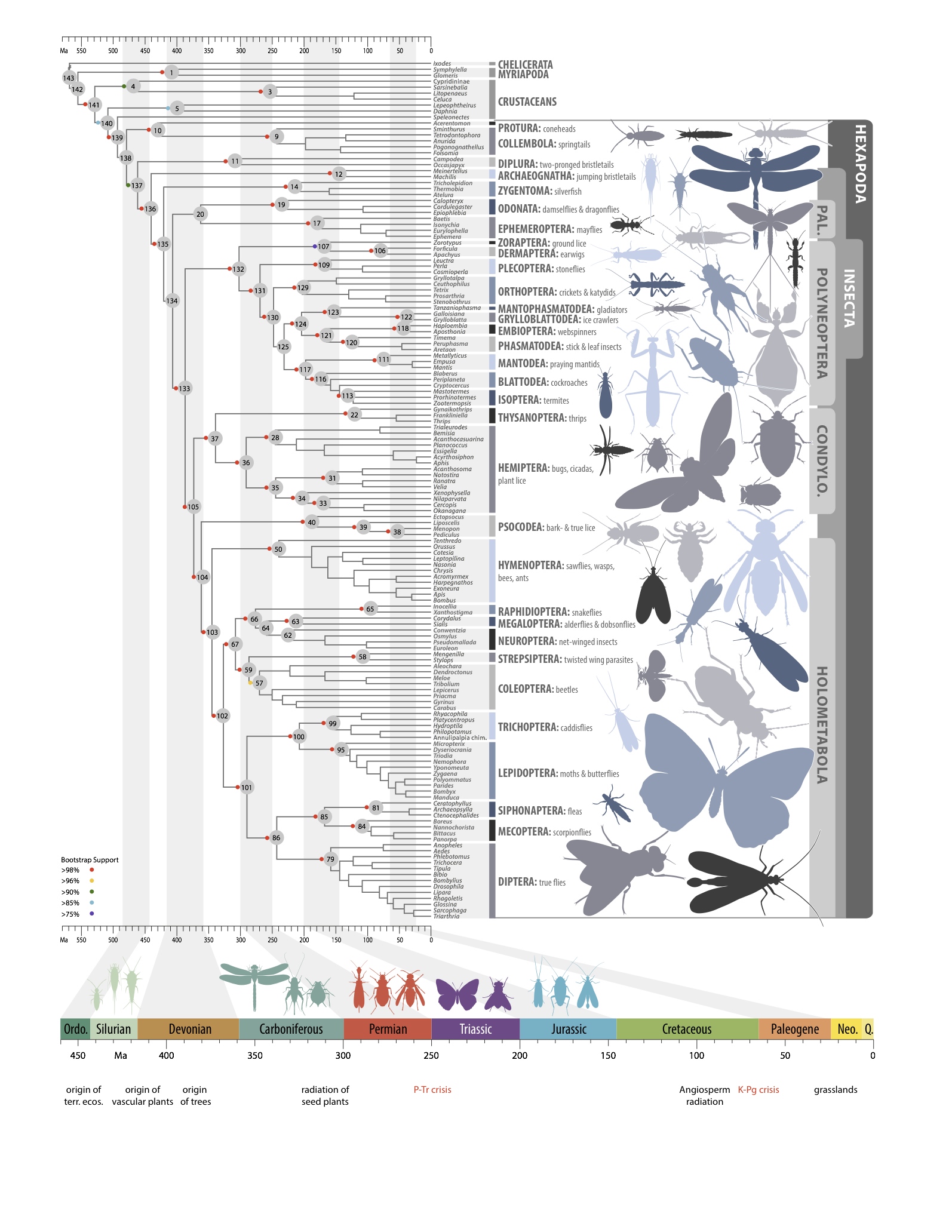

The first-ever comprehensive evolutionary tree of insects was recently created by a group of researchers from around the world. This phylogenetic tree, built from genetic sequencing and fossil data, helps explain the relationships between different kinds of insects across millions of years of evolution.

Led by the 1000 Insect Transcriptome Evolution — or 1KITE — project in China, the researchers used 1,478 protein-coding genes from all of the major insect orders to construct an enormous dataset detailing the genetic makeup of all the major insect groups that exist today. They then compared this dataset with the insect fossil record to determine when different species evolved. [See photos from the insect family tree]

"We put together a team of over 100 people, and we included a lot of people that often get left out [of such projects] — like morphologists and embryologists and paleontologists — so that we wouldn't just have a tree, we'd have stories to tell about that tree," said Karl Kjer, a professor in the Department of Ecology, Evolution, and Natural Resources at Rutgers University in New Jersey, who was involved with the project.

Among the stories that can be told using the new tree is the origin story of insects. Fossil evidence suggests that the first insects lived about 412 million years ago, during the Early Devonian Period. But the researchers' phylogenetic data indicates that the largest group of insects, hexapoda, may have evolved even earlier, around 479 million years ago, during the Early Ordovician Period.

However, the data also suggest that in some cases, the fossil records that scientists have long relied on for information about when insects evolved is quite accurate, according to Jessica Ware, an assistant professor of evolutionary biology at Rutgers, who also participated in the study.

"I thought it was interesting how the fossil record and the molecular ages that we recovered were very close in some cases. That was surprising, because there had been a bit of debate about the ages of insects based on the fossil record," Ware told Live Science.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The timeline established by the researchers indicates that insects likely started colonizing the planet at around the same time as plants, and in some cases, even earlier. Flying insects evolved after complex ecosystems had already developed on land, about 406 million years ago, during the Early Devonian Period, the scientists said.

Now the researchers know for certain that insects can't be left out of discussions about the ecosystems of, say, the Jurassic Period, about 150 million years ago, Ware said.

"All of the key players were already around before the end of the Jurassic Period. When we picture Tyrannosaurus rex roaming the Earth, we can say there were dragonflies around, and probably grasshoppers and crickets and butterflies," Ware said.

And the insects that were buzzing and hopping alongside the dinosaurs weren't prehistoric-looking creatures that modern bug lovers wouldn't be able to recognize. The phylogenetic data suggest that these insects were actually very similar to the ones still roaming the planet today, according to Kjer.

"If you had a time machine and you went back to the Jurassic, we entomologists would recognize all of the insects and we could [classify] them into their proper order," Kjer said. "Many of them would look very similar to what we see today."

Of course, the fact that insects were buzzing around next to the dinosaurs also means that these creatures were on Earth long before the evolution of Homo sapiens. The same fly you might swat today is not much different (if it's different at all) from the fly a caveman might have swatted away 200,000 years ago.

The researchers' findings were published today (Nov. 6) in the journal Science.

Follow Elizabeth Palermo @techEpalermo. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science .