Gene-Silencing and the 'Arctic' Apple (Op-Ed)

Margaret Mellon is a science policy consultant who specializes in food and agriculture. She contributed this article to Live Science's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

Biotechnology is heading into the Garden of Eden. A Canadian corporation, Okanagan Specialty Fruits, is offering a genetically engineered apple that doesn't brown after it's bruised or sliced. The U.S. Department of Agriculture appears to be on the brink of deregulating the so-called "Arctic" apple, allowing it to be planted and sold without any further oversight. The company won't label the apples as genetically engineered, but will sell the fruit under the Arctic apple brand.

To many people, reduced browning may not seem like such a big deal. The new apples won't be any cheaper, taste any better or carry any fewer toxic chemicals than conventional apples do. But Okanagan hopes the apple will appeal to fresh-cut apple-slice processors, the food service industry and consumers unwilling to splash sliced apples with lemon juice. [GMOs: Facts About Genetically Modified Food ]

It is not yet clear how tempting the Arctic apples will be. Cut-apple processors account for only a small part of the apple industry. Growers of fresh apples — the much larger part of the industry — worry that genetically engineered apples will stir unwanted controversy and perhaps tarnish the apple's image as a traditionally healthful product. Also, some consumers may value browning as an indicator of freshness.

Gene silencing: The next wave of genetically engineered crops

Whatever challenges it poses to the apple industry, the Arctic apple raises a much larger issue for the public: how to evaluate the risks of the next big wave of genetically engineered crops and foods.

Does the Arctic apple pose risks to health and the environment? As of right now, the government doesn't know. That's because the Arctic apple is the product of complex new genetic engineering techniques that the USDA is just learning how to evaluate.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

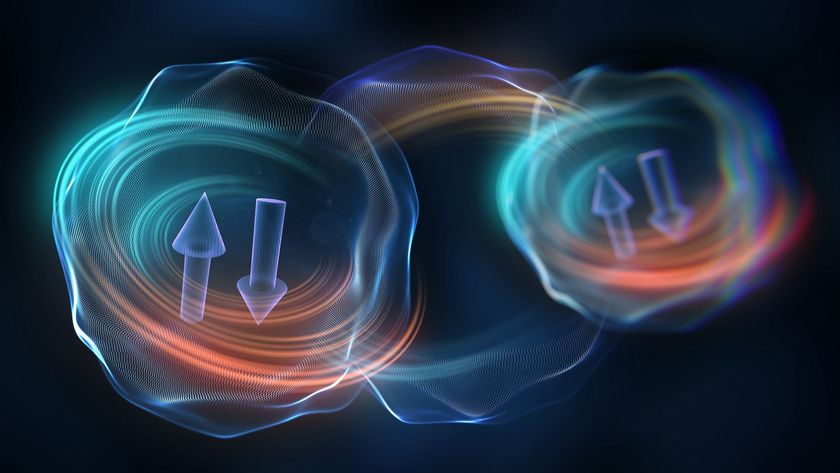

Unlike earlier cut-and-splice techniques focused on DNA, the new techniques are based on the manipulation of RNA molecules.

RNA molecules recognize and bind to DNA sequences as cells go about their routine activities. Organisms are like orchestras; they only work well if each instrument (or gene) plays when it is supposed to and at the right level.

Figuring out how the tens of thousands of genes that make up organisms play at the right levels at the right time has been a major focus of molecular biologists for the last 15 years. Craig Mello and Andrew Fire were awarded a Nobel Prize in 2006 for the seminal discovery that double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) could silence genes and affect which genetic instruments play when.

Since then, scientists have discovered many more types of RNA involved in genetic orchestration, butdsRNA remains central to those processes. Genetic engineers can now use gene silencing to dial back the expression of genes. The Arctic apple has been engineered to silence the polyphenol oxidase (PPO) enzymes responsible for browning in apple flesh after the fruit is cut.

Concerns about turning off genes

Is there any reason to worry about turning genes off? Yes. RNA manipulations may end up turning down, or off, genes other than those that were targeted.

How could that happen? Well, as detailed in commentsto the USDA on the Arctic apple from the Center for Food Safety, it turns out that many genes contain similar, or even identical, stretches of DNA. A dsRNA targeted to one gene might turn off, or down, those other genes. Similar DNA stretches can be found in unrelated genes scattered around the genome or, as in the case of the Arctic apple, in a family of genes closely related to the target genes.

The PPO genes that cause browning in apples are part of a family of 10 or 11 closely related genes. Okanagan's process is aimed at only four of the genes, but because the gene sequences are very similar it will probably have effects on all of them.

Why does that matter? PPO gene families perform multiple functions in plants. Little is known about the PPO gene family in apples, but in other plants, PPO genes are known to bolster pest and stress resistance. This raises the question of whether non-browning apple trees might be more vulnerable to disease and require more pesticides than conventional apples — and whether they might transfer those vulnerabilities to other apple trees.

But the company's petition to the USDA for deregulation did not analyze PPO gene functions, other than browning, in apples — nor did it measure the levels of PPO gene expression in the untransformed apples to compare with those in the transformed apples.

Okanagan's petition regarding its apple also did not analyze whether it has inadvertently silenced genes outside the PPO family. In addition to failing to properly characterize the genetically engineered apple, the Okanagan assessment gave short shrift to potential effects on wild pollinators and honeybees, human nutrition and weediness.

Getting a handle on gene silencing

The stunning inadequacy of the Arctic apple risk assessment is largely the USDA's fault. The agency just accepted what the company gave it and did not require specific information on the risks of gene silencing.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration, which offers voluntary food safety reviews of genetically engineered foods, also has yet to publish its approach to the evaluation of gene-silencing risks.

The FDA and the USDA need new protocols for evaluating these complex new technologies. Modern genomics research has provided scientists with powerful tools to identify nontarget genes that might be turned off by gene silencing.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency took a step in the right direction last January by convening experts to look at that agency's ability to evaluate dsRNA molecules used as pesticides. After noting some of the ways gene silencing to control pests might go wrong, the committee concluded that the EPA's tried-and-true methods for evaluating chemical pesticides would not work to assess such risks and that new approaches, including genomics, were needed.

The USDA and the FDA should convene their own expert panels on gene silencing. Once the experts have brainstormed how gene-silencing technologies might misfire in the environment and food safety arenas, the committees will be able to make recommendations on how to evaluate the risks of the new technologies. Then, the USDA and the FDA will know what information to require from Okanagan and other companies to evaluate their products.

Until such workshops are held and assessment protocols developed, the U.S. government should hold back on the approval of products based on gene silencing.

Let's be smarter than Eve and not bite into this apple until we know whether there is a worm inside.

Follow all of the Expert Voices issues and debates — and become part of the discussion — on Facebook, Twitter and Google+. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This version of the article was originally published on Live Science.