It's Really Richard: DNA Confirms King's Remains

Battled-scarred bones found under an English parking lot two years ago really do belong to the medieval King Richard III, according to a new analysis of genetic and genealogical evidence.

"The evidence is overwhelming that these are indeed the remains of Richard III," University of Leicester geneticist Turi King said during a press conference.

Just how overwhelming? King and colleagues put pretty astounding odds on their claim: Taken together, the genetic, genealogical and archaeological evidence show that there's a 6.7 million to 1 (or 99.99 percent) chance that the 500-year-old skeleton is the king's. [See Images: The Search for Richard III's Grave]

The new research into Richard's genes also revealed that the king had blue eyes and blond hair, at least in childhood. The findings were published today (Dec. 2) in the journal Nature Communications.

The king in the car park

Richard III, the last king of the House of York, died at age 32 during the 1485 Battle of Bosworth, the final fight of the Wars of the Roses, which saw the Tudor dynasty take over the British throne. Historic records indicate that Richard was buried at a monestery called Greyfriars in Leicester. But after the dissolution of the monastery in 1538, its location, and thus the location of Richard's grave, was lost to history.

In August 2012, a team of archaeologists from the University of Leicester renewed the hunt for Richard's final resting place. They began excavating a parking lot in Leicester and soon found traces of the lost monastery.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

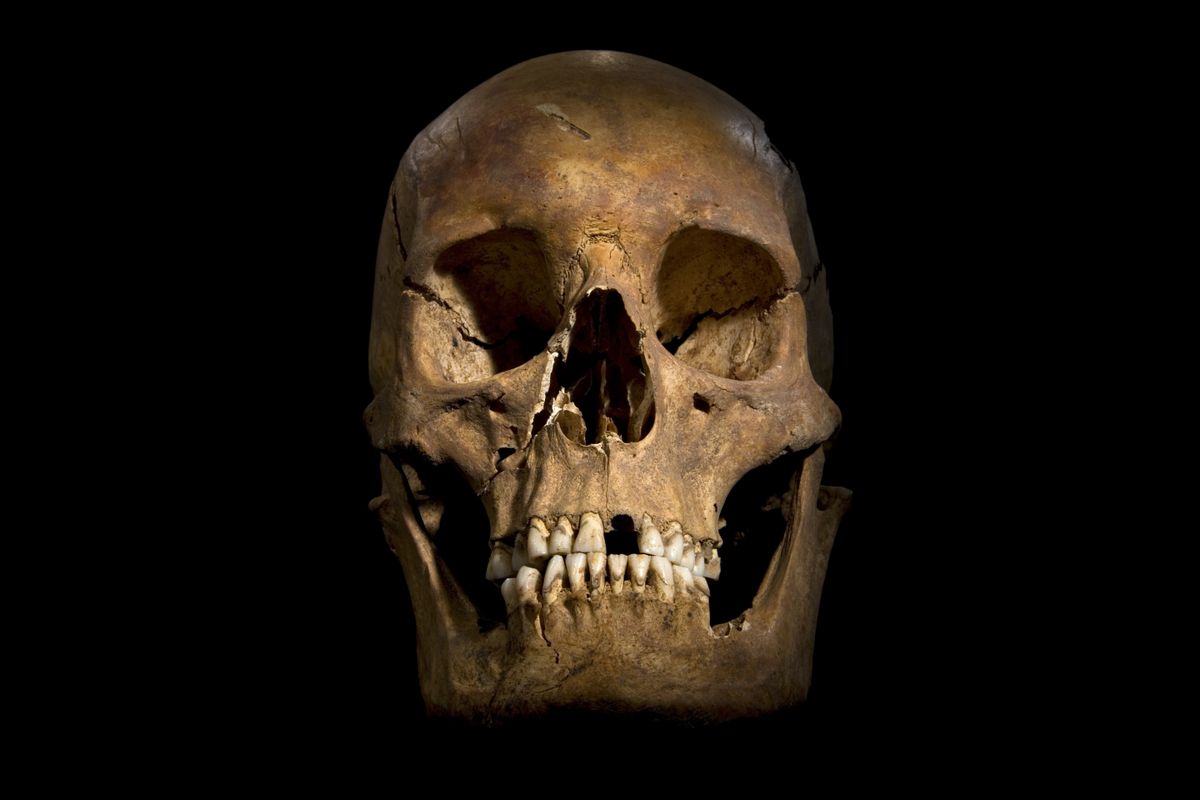

By mid-September, the archaeologists found a skeleton in the monastery's choir that seemed to be a promising candidate for Richard. The king was said to have had uneven shoulders, and this skeleton had signs of the spinal disorder scoliosis. The bones also had battle wounds, including fatal blows to the skull, which matched accounts of Richard's death.

Mom genes

King and colleagues looked for a match between Richard's mitochondrial DNA and the mitochondrial DNA of the king's living relatives. This type of DNA is found in the energy-producing centers of cells, the mitochondria, and it is only passed down through the mother. Accordingly, the researchers looked at genetic material from two female-line descendants of Richard's sister Anne of York: a man named Michael Ibsen, 19 generations removed from Richard, and a woman named Wendy Duldig, 21 generations removed from Richard.

King said the researchers found "an absolute perfect match" between Ibsen's mitochondrial DNA and that of the skeleton. There was just a one-letter difference in Duldig's sequence.

"That is perfectly what we would expect," King told reporters in a press conference. "The mitochondrial DNA has to be copied to be passed down through generations, and you get little typos."

These matches are not likely to have been random, the researchers said, because this particular mitochondrial DNA sequence seems to be rare; it didn't match with any of the control sequences in a database of 26,127 European complete mitochondrial DNA types.

It's true that dozens of Richard's kinsman would have been carrying the same sequence of mitochondrial DNA, and the researchers also investigated the possibility that instead it is one of Richard's relatives who was the person buried at Greyfriars.

But Kevin Schürer, a historian at the University of Leicester, said historical records eliminated that scenario for all but one of Richard's relatives: Robert Eure, who was born around the same time as Richard but whose place and cause of death remain unknown. Still, Schürer said there is no record indicating Robert Eure's family fought at the Battle of Bosworth, and since he was a Knight of the Order of St. John of Jerusalem, he likely spent a lot of time in the Mediterranean and perhaps died there.

You are not the father

The researchers also looked for living relatives who might share Richard's Y chromosome, which, like mitochondrial DNA, is passed down to children virtually unchanged. But the Y-chromosome is only passed down from father to son. And comparing this evidence against historical records can be problematic, because, as anyone who has watched "Maury" knows, the presumed father isn't always the actual father of the child. The same goes for royals.

The study authors found five men who, according to their family tree, should be male-line relatives of Richard III. All of these men share a common ancestor, Henry Somerset, fifth Duke of Beaufort, who died in 1803.

These men did not have the same Y chromosome as Richard. The researchers found one "break" in the male line between the five donors and Henry Somerset, meaning one of the donors was not genetically descended from Henry. But there was also at least one break somewhere in the 19 links between Richard III and Henry.

That's not to say Richard's Y chromosome is useless. It could eventually be used to acquit Richard of the murder of his two nephews. The young sons of Richard's brother Edward IV were not seen in public after Richard took the throne, leading to speculation that he had them murdered. (That accusation is repeated in William Shakespeare's play "Richard III," which paints the king as a villain.) Bones found during work on the Tower of London in the 17th century were accepted as the remains of the two boys and were buried in Westminster Abbey. A DNA test could prove whether those remains are authentic.

"We don't know for sure whether or not those remains are those of the princes," Schürer said. "We now have the Y chromosome of Richard III, and that should be identical to both of the princes since they shared the same paternal line."

But the fate of the two princes might remain a mystery. As The Guardian reported last year, the Church of England is unlikely allow any forensic testing on the remains out of fear of a flurry of royal exhumations.

There is also grave in Kent purported to hold the remains of an illegitimate child of Richard III, named Richard Plantagenet of Eastwell. He should have the same Y-chromosome as his father, and a DNA test might reveal whether or not that's the case, Schürer said.

For now, Richard's genome by itself could help solve one historical puzzle: the king's appearance. All surviving portraits of Richard III were created about 25 years after his death, so their reliability has been questioned. The king's genes revealed that he had blue eyes and blond hair, at least in childhood, though his locks may have darkened as he aged. This suggests that the so-called "Arched-Frame Portrait" in the Society of Antiquaries, which depicts Richard with blue eyes and light brown hair, may be the most accurate.

Follow Megan Gannon on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.