Two-Headed Baby Salamander Isn't Radioactive, But It Is Weird

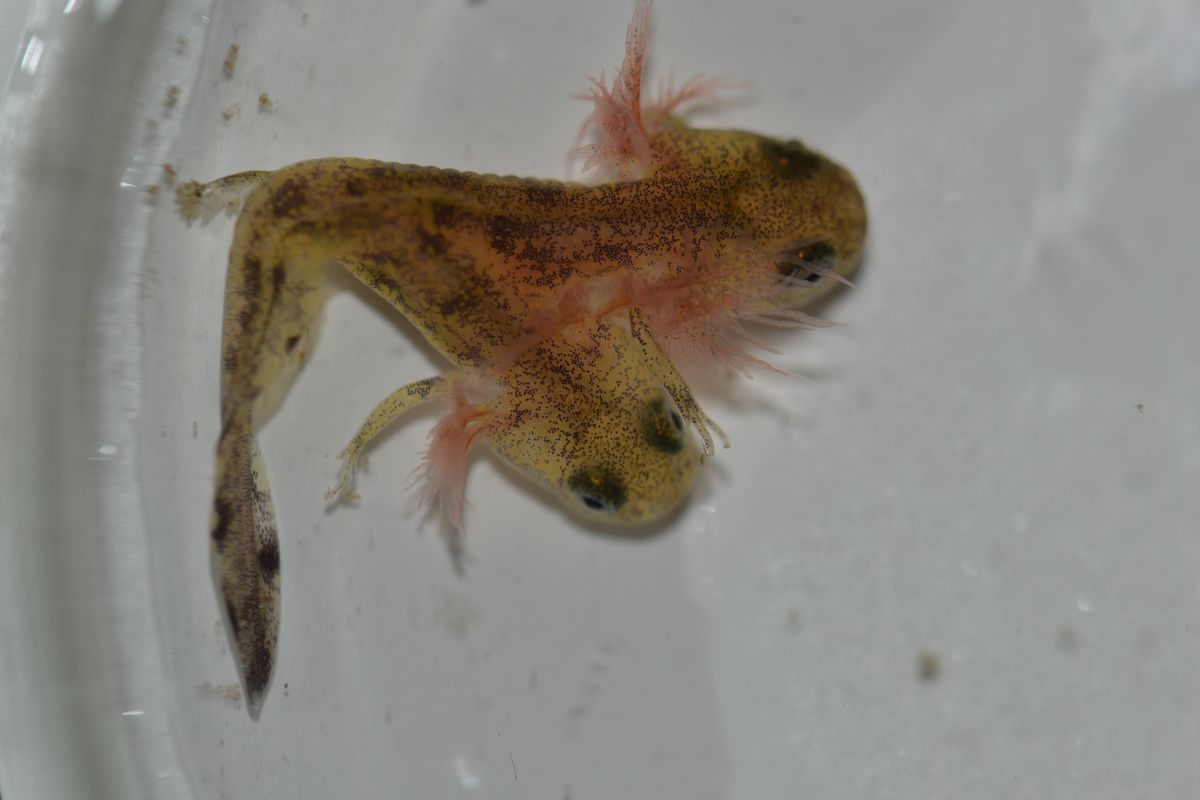

Just call them "Arne" and "Sebastian." Those are the monikers given to the two separate heads of one baby salamander that was born last week in a lab in Israel.

Two heads are likely not better than one for the Near Eastern fire salamander (Salamandra infraimmaculata), which was born, alive, in a laboratory at the University of Haifa in Israel. Researchers aren't sure why the salamander tadpole has two noggins, but say random mutations or environmental pollution could be culprits.

"I could speculate, but it would be pure speculation," Leon Blaustein, an ecologist whose lab discovered the salamander, told Live Science. [The 12 Weirdest Animal Discoveries]

Strange salamander

Blaustein's team had collected pregnant female fire salamanders from the wild to give birth in the lab. (This species of salamanders gives birth to live young in a larval or tadpole stage.) A female that was gathered from a site called Kaukab Springs in the Galilee Mountains, gave birth to the two-headed tadpole.

Both heads move, Blaustein said, but so far, scientists have seen only one preying upon a salamander baby's favorite meal, insect larvae. Blaustein gave the heads their names to honor two German scientists, Arne Nolte and Sebastian Steinfartz, with whom he collaborates on studying fire salamander ecology.

The Near Eastern fire salamander is listed as "near threatened" by the International Union for Conservation of Nature; in Israel, it is locally endangered, Blaustein said. Humans are the main reason the species is struggling. According the IUCN, human development is shrinking salamander habitat in Israel, Lebanon and possibly Syria. Water pollution is another threat, as is human water use for irrigation. Dams can disrupt salamander habitat by flooding the temporary, shallow pools and small streams where the amphibians thrive.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In Israel, Blaustein said, automobiles are killing salamanders on roadways and are a major problem.

Mysterious causes

Salamander deformities are rare, Blaustein said, though not unknown. His lab has recorded cases of salamander larvae born with six legs instead of four, or with only partial heads. Finding two heads on one body is particularly unusual, he said.

Tracing the cause of such deformities is difficult. Amphibians are sensitive to environmental changes and pollution, Blaustein said, which makes them early indicators that something is going wrong in the environment. And the Kaukab Springs site is one of the more polluted breeding sites for these salamanders, he said. However, those factors alone do not prove that pollution caused the defect.

"It would be absolutely incorrect to suggest that this single observation of a two-headed salamander" suggests human-caused damage to the environment, Blaustein said.

After the University of Haifa released a statement that included the researchers' speculation that the two-headed defect might have been caused by pollution or radiation, some news outlets reported that the salamander is radioactive, Blaustein said. It is not.

The salamander isn't the only wild animal found with two heads where only one was supposed to grow. In 2013, a fisherman in Florida caught a pregnant shark and found that one of the live fetuses inside her womb had two heads. Another 2013 find in Australia of an "oddly shaped, pale object" turned out to be a stillborn baby ray with two heads. This defect can occur for several reasons, including an embryo that begins to split into twins, but does not complete the process.

More recently, in August 2014, a dead, two-headed dolphin washed ashore in Turkey. Arguably even stranger was the 2011 discovery of a "Cyclops shark," a one-eyed dusky shark fetus found off the coast of Mexico. "Cyclopia" is a developmental defect in which only one eye forms.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Most Popular