World's Saltiest Body of Water Seen from Space (Photo)

The world's saltiest body of water, hidden away in a dry Antarctic valley, had its portrait taken earlier this year by a NASA satellite.

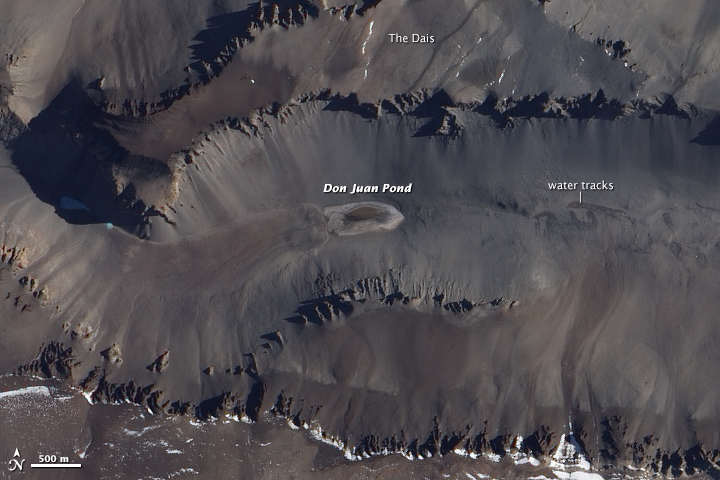

The image of the Don Juan Pond, a very shallow lake located in the lowest part of Antarctica's Upper Wright Valley, that NASA released today (Dec. 29) was taken by the agency's Earth Observing-1 satellite.

With a salinity higher than 40 percent, the Antarctic pond is even saltier than the Middle East's Dead Sea (34 percent) and Utah's Great Salt Lake (whose salinity varies between 5 and 27 percent). For comparison, the average salinity of the world's ocean is about 3.5 percent. [The Most Mars-Like Places on Earth]

Scientists don't know whether the supersalty lake supports microscopic life. If it does, that could suggest that life exists or existed in the past on Mars, which contains plenty of salt and used to have lots of water.

"There is certainly biology in the vicinity of the pond, and some evidence for biologic activity in the pond itself, but this activity could be explained by [nonliving] processes," Brown University geologist Jay Dickson told NASA.

The pond is in the McMurdo Dry Valleys, where winter temperatures can drop to as low as minus 58 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 50 degrees Celsius), and most of the ponds and lakes are covered by quite a few feet of ice.

But the ankle-deep Don Juan Pond is so salty that it never freezes. The water is rich in the salt calcium chloride, which interferes with the formation of ice by preventing the water molecules from forming crystals.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In the above image, the pond is an ellipse that lies at the bottom of a basin, between the Dais plateau to the north and the Asgard Range to the south. The lake is slightly darker than the larger lake-bottom region surrounding it.

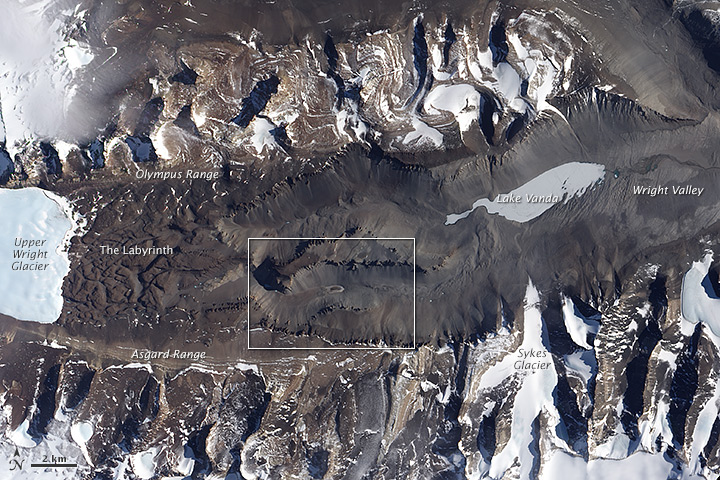

The image to the right shows a wider view of Don Juan Pond, depicting a network of channels carved into the bedrock east of the Wright Upper Glacier, and the frozen Lake Vanda to the northeast of the pond. The images were captured on Jan. 3, 2014.

It was long thought that Don Juan Pond was fed by water bubbling up from the ground, but recent research suggests that the lake's water comes from the atmosphere.

In one study, Dickson and James Head, also a geologist at Brown University, set up cameras that took thousands of time-lapse photos of the lake. The salts in the soil near the pond bring moisture from the air into the soil through a process known as deliquescence. Then, the salt-rich water flows down toward the pond, often mixing with melted snow and ice, which create dark water tracks on the ground, the researchers said.

Follow Tanya Lewis on Twitter. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.