Growing Human Kidneys in Rats Sparks Ethical Debate

Researchers say they have developed a new technique that will get more kidneys to people who need transplants, but the method is sure to be controversial: The research shows that it is feasible to remove a kidney from an aborted human fetus, and implant the organ into a rat, where the kidney can grow to a larger size.

It's possible that further work could find a way to grow kidneys large enough that they could be transplanted into a person, the researchers said, although much more research is needed to determine whether this could be done.

"Our long-term goal is to grow human organs in animals, to end the human donor shortage," said study co-author Eugene Gu, a medical student at Duke University and the founder and CEO of Ganogen, Inc., a biotech company in Redwood City, California. [The 9 Most Interesting Transplants]

Such organs could also be used to test drugs before human trials are started, which would help avoid the risks associated with using untested compounds in people, Gu added.

The new findings will be published tomorrow (Jan. 22) in the American Journal of Transplantation.

But the research raises a number of ethical questions, including whether it is acceptable to use human fetal organs in research, or to transplant human organs into animals. If the research moves forward, it must be determined that the organs were obtained with proper consent, and that the research was conducted with adequate oversight, experts said.

Human-rat transplants

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

More than 123,000 people in the United States currently need an organ transplant, and about 21 people die each day waiting for one, according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Previously, other scientists had attempted to grow immature human kidneys in the abdomens of mice, but the new research "is definitely the first time an actual whole human organ has been grown in an animal, and has sustained the life of that animal," Gu told Live Science.

In the new study, Gu and his colleagues obtained human fetal kidneys from Stem Express, a Placerville, California-based company that supplies researchers with tissue from deceased adults and fetuses. The people who donated the fetal tissues gave consent for the kidneys to be used in research, and the scientists were completely separated from the donation process, Gu said.

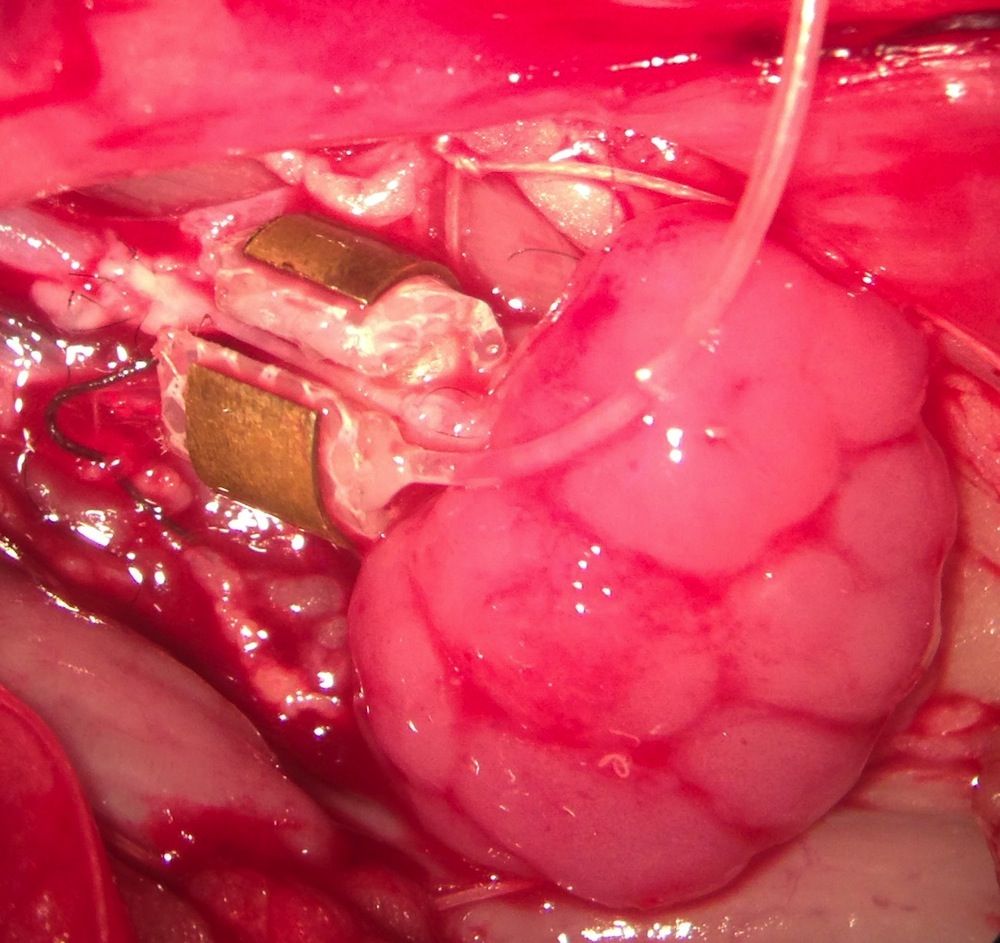

The researchers transplanted the fetal kidneys into adult rats that lacked an immune system (so as to avoid tissue rejection), and connected the animals' blood vessels to the organs using a challenging procedure that involved tiny stitches, about three to four times smaller than the width of a human hair.

One of the main reasons that previous attempts to transplant fetal organs into animals have failed is due to a difference in the blood pressure between human fetuses and adult animals. In most adult animals, including rats, the average blood pressure is about three times higher than it is in human fetuses. If a fetal organ is transplanted without adjusting the pressure, "the organ basically hemorrhages everywhere," Gu said.

To get around that problem, Gu's team developed a device, called an arterial flow regulator, which they fitted around the rats' blood vessels to decrease the pressure of the blood flowing into the fetal kidneys.

About a month after the researchers transplanted the fetal kidneys into the rats, the scientists surgically removed the animals' own kidneys. The rats that received the transplanted kidneys survived an average of four months after transplant, and one even survived for 10 months, Gu said. By comparison, a control group of rats that did not receive a transplanted kidney lived for only three to four days after having their kidneys removed, the researchers said.

In addition to kidneys, the researchers have also transplanted human fetal hearts into rats, Gu said. The work is still in progress, but the researchers said it may also be possible to use the method with other organs. "This technology is applicable not just to the kidney, but to every kind of [blood-supplied] organ in the body," Gu said.

In the short term, fetal organs grown in animals could be used to test drugs that can't normally be tested in living humans. Ultimately, the researchers plan to transplant the kidneys into larger animals, such as pigs, where the organs could grow large enough to be transplanted back into people, Gu said.

But this idea may be controversial among the American public, bioethicists say.

Ethical questions

Firstly, there's the issue of using human fetal organs in research at all, said Hank Greely, an ethical and legal expert on biomedical science at Stanford Law School. [Humans 2.0: Replacing the Mind and Body]

"The key issues are the existence of the pregnant woman's consent and the total separation of the decision to abort from the decision to let the fetal remains be used in research," Greely told Live Science. In other words, a woman must have already decided to have an abortion before she can be asked whether she is willing to donate the fetus for research.

For the organs used in the new study, "All donors are properly consented through an Institutional Review Board (IRB) consent, and donors are made aware of the potential use of any sample that we collect," said Cate Dyer, CEO and founder of Stem Express, the company that provided the kidneys for the study. This includes being told that the tissue could be transplanted into animals.

In addition, the donors did not receive any direct benefits for donating the fetal tissue, Dyer noted, writing in an email to Live Science.

There's also the additional ethical issue of implanting human fetal organs into nonhuman animals, Greely said. Researchers "do this a lot — make nonhuman animals with some human parts — so we can study the human parts outside of a human, he said.

Most of such research is done with cells or tissues, and not with whole organs, but the procedure isn't ethically objectionable unless it involves brains, sex organs or "externally visible things that provide a human appearance to the animal," Greely said.

In 1987, Swedish scientists transplanted human fetal brain tissue into human patients who had Parkinson's disease, according to a study published in the New England Journal of Medicine. A moratorium was placed on the use of this therapy in 2003, but that was lifted in 2014.

Finally, there's the issue of oversight of kidney transplants in the animals.

The study was approved by Ganogen's Human Fetal Transplantation Research Ethics Committee, which consists of two board-certified transplant surgeons at separate academic centers, two members of the general public not affiliated with the institution and one board-certified general clinician, the researchers said.

But some experts say fetal organs will never be used for human transplants.

Moral discomfort

Arthur Caplan, a bioethicist at NYU Langone Medical Center, said the study itself did not concern him.

However, "there is no way we're ever going to use fetal human kidneys or any other solid organs for transplant," Caplan said. "American society is morally uncomfortable enough about abortion that growing organs from fetal remains will never be accepted, and will be banned in state after state."

The researchers said they hope Caplan is wrong. "There would, at the very least, be the role of using human fetal organs obtained from therapeutic abortion procedures [in which an abortion is done because the mother's life is in danger] to save a baby with a fatal disease," Gu said.

Given the major shortage of children's organs available for transplant, "the U.S. public may find this technology more palatable if they we restrict the organ recipients to only neonatal and fetal patients who have basically no other alternative to save their lives," Gu added.

The study did not receive any federal, state or local government funding; it was funded privately through donations from the researchers' family and friends and other small investors.

Editor's Note: This article was updated at 5:10 p.m. ET January 21 to clarify the date the study will be published.

Follow Tanya Lewis on Twitter. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.