La Niña Events May Spike with Climate Change

The extremely strong La Niña events that can shake up global weather patterns may soon hit nearly twice as often as they did previously, due to global warming, researchers say in a new study.

The researchers analyzed global climate models that can simulate extreme La Niña events. Results showed that extreme La Niña events may soon strike about every 13 years, as opposed to about every 23 years, as they do now.

The findings do not suggest a regular schedule of extreme La Niña events every 13 years, said lead study author Wenju Cai, a climate scientist at the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization in Aspendale, Australia. "We're only saying that on average, we expect to get one every 13 years," Cai explained. "We cannot predict exactly when they will happen, but we suggest that on average, we are going to get more."

La Nina events can trigger floods, heat waves, blizzards and hurricanes worldwide, researchers said. The new findings also suggest that some areas could get whiplashed with weather of opposite extremes from year to year — for example, droughts one year and floods the next, the scientists added.

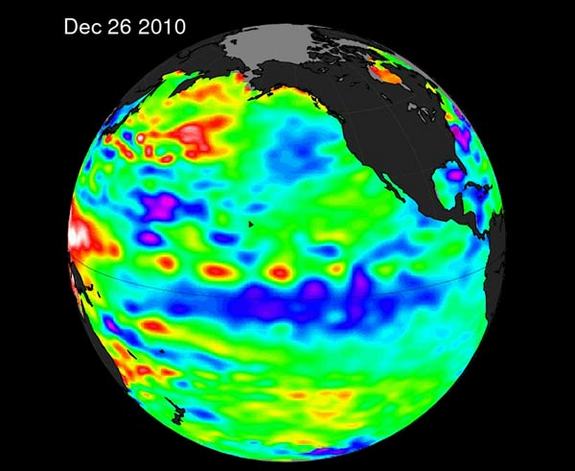

La Niña, which is Spanish for "little girl," involves unusually cool waters in a belt 5,000 miles (8,000 kilometers) long across the equatorial Pacific Ocean. It is the counterpart of El Niño, which is Spanish for "little boy" and involves unusually warm waters in the same area. South American fisherman named El Nino for the baby Jesus, after noticing that the ocean would heat up around Christmastime. [Weirdo Weather: 7 Rare Weather Events]

Both El Niño and La Niña can alter wind and water currents across the globe, causing extreme weather that can kill thousands of people and result in billions of dollars in damage.

"During the 1998-1999 La Niña event, the southwestern United States experienced one of the most severe droughts in history," Cai said. In Venezuela at that time, flooding and landslides killed 25,000 to 50,000 people, and in China, floods and storms killed thousands and displaced over 200 million people. In Bangladesh, where over 50 percent of the country's land area flooded, food shortages and waterborne diseases killed several thousand people and affected over 30 million. During that La Niña, Hurricane Mitch, one of the deadliest and strongest hurricanes on record, killed more than 11,000 people in Honduras and Nicaragua, Cai said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In 2014, Cai and his colleagues predicted that as the globe warms due to increased levels of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, extreme El Niño events may hit about every 10 years, instead of about every 20 years as they do now. Since El Niño is essentially the opposite of La Niña, "one would have thought if extreme El Niño is increasing in frequency, perhaps the frequency of extreme La Niña might decrease," Cai said. But they found the opposite.

The scientists also found about 75 percent of extreme La Niña events will occur immediately after an extreme El Niño event.

"The implications are profound," Cai told Live Science. "It means affected regions will experience opposite extremes from one year to the next."

The researchers noted their finding is counterintuitive, since it predicts that global warming can lead to more intense cold-water related activity such as extreme La Niña events. However, Cai explained that a region of Southeast Asia between the Indian and Pacific Oceans known as the Maritime Continent, which includes Indonesia, Philippines and Papua New Guinea, will warm faster than the central Pacific Ocean in a warmer world. This difference in temperature can drive unusually strong easterly winds that drive warm water westward and pole-ward, which in turn brings colder water from the deep ocean closer to the surface.

Cai explained why extreme La Niña events will usually occur immediately after an extreme El Niño event: During an extreme El Niño event, heat from the upper layers of ocean water gets released into the atmosphere, driving circulation in the atmosphere and ocean that can ultimately enhance Pacific cooling.

"Our results call for measures to reduce greenhouse gas emissions so as to reduce such risks," Cai said.

The scientists detailed their findings online today (Jan. 26) in the journal Nature Climate Change.

Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Originally published on Live Science.