People with Dementia May Have Hidden Talents, Strange Case Shows

A 60-year-old businessman lost his job and much of his personality to dementia. But despite his mentally debilitating condition, he learned to play the saxophone for the first time in his life, and played exceptionally well, according to a new report of his case.

The Korean man, called J.K. in the report, had developed a form of dementia known as frontotemporal dementia (FTD), in which the frontal and temporal lobes of the brain shrink. As a result of the condition, J.K.'s personality gradually changed. He started behaving inappropriately in social situations, and began having language and memory problems. But thanks to encouragement from his wife, he took up learning to play a musical instrument.

He even ended up outperforming other, healthy students in his saxophone class, according to the report, published Jan. 14 in the journal Neurocase.

The case shows that people with dementia may have hidden talents and abilities that can emerge when given the opportunity, said Dr. Daniel Potts, a dementia specialist in Alabama and a member of the American Academy of Neurology. Potts was not involved in the man's case but called it "fascinating."

"If we really give people an opportunity — and don't give up on them, and try to affirm their traits and personhood — many of them may be able to do things like this." [16 Oddest Medical Case Reports]

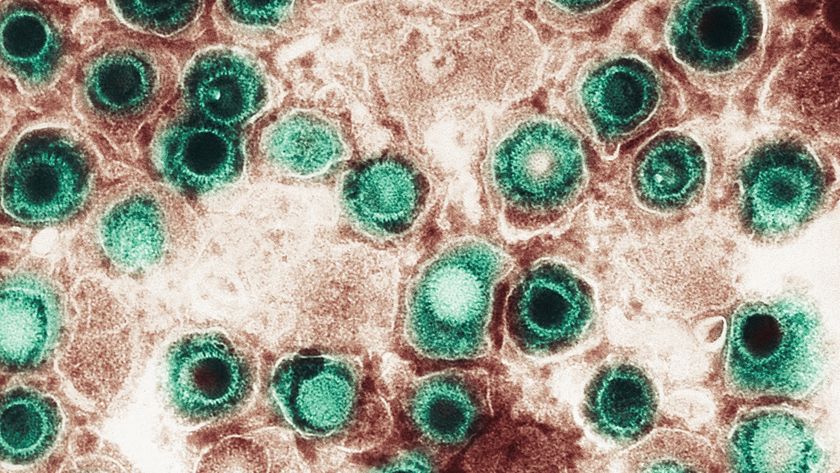

FTD is a type of dementia that tends to affect people who are younger than those affected by other types of dementia, such as Alzheimer's.

Potts said that FTD is also different from Alzheimer's in that, "rather than short-term memory loss, you have more of a behavioral problem that manifests itself as inappropriate social behavior, disinhibition, withdrawing from normal social engagement, and you get some language problems as well."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

However, patients with FTD may keep skills they've learned, such as playing games, and even show an artistic enhancement of their visual or musical abilities, as previous studies have reported.

"The thing that was different about this case was that this individual took up playing a musical instrument during the time after he was diagnosed with FTD and had never done that before — and I think this makes this case unique," Potts said.

In contrast to skills like language, movement and memory, the ability to both appreciate and perform music involves a large proportion of the brain, so diseases that involve only certain parts of the brain may not affect all areas involved in music, Potts said. People may get even better at art because, as the parts of the brain that are involved in inhibitions begin to deteriorate, their artistic creativity may be unleashed, he said.

According to researchers in South Korea who wrote about the case, J.K. began to show symptoms of dementia at age 58, when his wife of 32 years noticed odd changes in his personality. For example, during conversations at work, J.K. would say his thoughts out loud, without considering the feelings of his co-workers, and he did not appear to care at all when his wife was hospitalized for an illness.

A year later, J.K. who had always been gentle and introverted, started to become aggressive and impulsive. "He often became angry over trifling matters, spoke ill of others, and even became both verbally and physically violent," the researchers wrote.

At age 59, after receiving a diagnosis of FTD, J.K. began to take saxophone lessons for 2 hours daily, because his wife thought that playing a musical instrument would soothe his abnormal behaviors. Previously, he had not had any musical education.

"At first, it took a long time for him to learn how to read musical notes and to play the saxophone. However, his skills progressed, and soon, he was able to play new, unfamiliar songs every two to three months," the researchers wrote in their report.

When examined at age 61, three years after the start of his symptoms, J.K. was found to have some behavioral problems, but his aggressiveness and anxiety were less severe than when his condition was first diagnosed, according to the report.

Learning to play an instrument might have been therapeutic for J.K., Potts said.

"I think that it probably gave him a way to express himself when he was losing his language abilities, when he was no longer able to get his emotions out in a proper way, perhaps," Potts said. "Maybe this gave him an outlet to deal with some of that."

Giving dementia patients a chance to explore their artistic talents could be beneficial for both patients and their caregivers, Pott said. It may be hard to maintain a relationship with someone who has such cognitive problems, but people may be able to connect through music and art, he said.

Email Bahar Gholipour. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Originally published on Live Science.