Images: 2 Fossils of Tiny Early Mammals

The fossils of two notable species have been discovered in China: the oldest tree-dwelling mammal ancestor ever identified and the earliest subterranean mammal ancestor, which sports shovel-like paws. The findings reveal a diverse landscape of mammalian creatures some 160 million years ago. Here's a look at the new mammal discoveries. [Read full story about the mammalian fossil finds]

Horny claws

The fossil of the oldest tree-dwelling mammal ancestor, now dubbed Agilodocodon scansorius, was found preserved in two rock slabs (shown here). The specimens were found in 165-million-year-old lake sediments at the Daohugou Fossil Site of Inner Mongolia of China. When alive, the animal would have been equipped with horny claws on its hands and feet, as well as a coat of hair and fur, all of which were preserved in the fossils. (Photo by Zhe-Xi Luo, the University of Chicago)

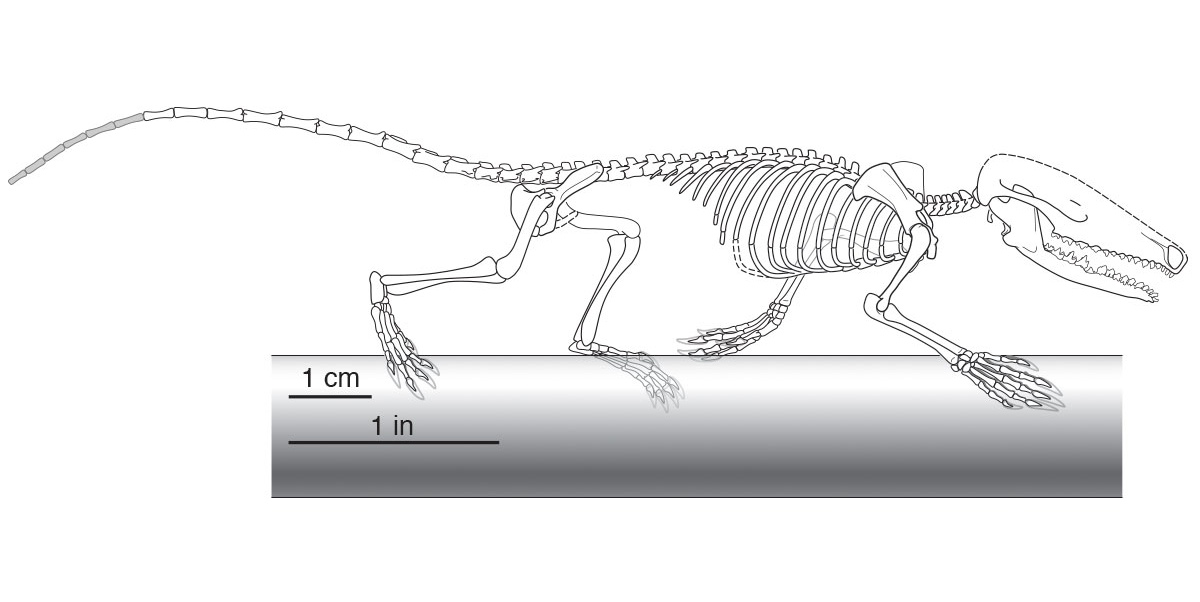

Scrawny skeleton

A skeletal reconstruction of A. scansorius revealed its skull would have been about 2.7 centimeters (about an inch) long, attached to a body spanning about 13 cm (5 in.), the researchers estimated. (Illustration by April I. Neander, the University of Chicago)

Agile tree climber

Here's what the ancestral mammal may have looked like when alive. Weighing between 1 and 1.4 ounces (27 and 40 grams), A. scansorius was likely an agile tree-dweller that used its specialized incisors to feed on tree sap; its molars would've helped the little beast feed on various other foods. (Illustration by April I. Neander, the University of Chicago)

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Furry beast

The fossil specimens of the subterranean mammal ancestor, named Docofossor brachydactylus, were discovered in lake sediments of the Jurassic Ganggou fossil site in Hebei Province of China. The fossil showed dense carbon furs around its skeleton, the researchers said. (Photo by Zhe-Xi Luo, the University of Chicago)

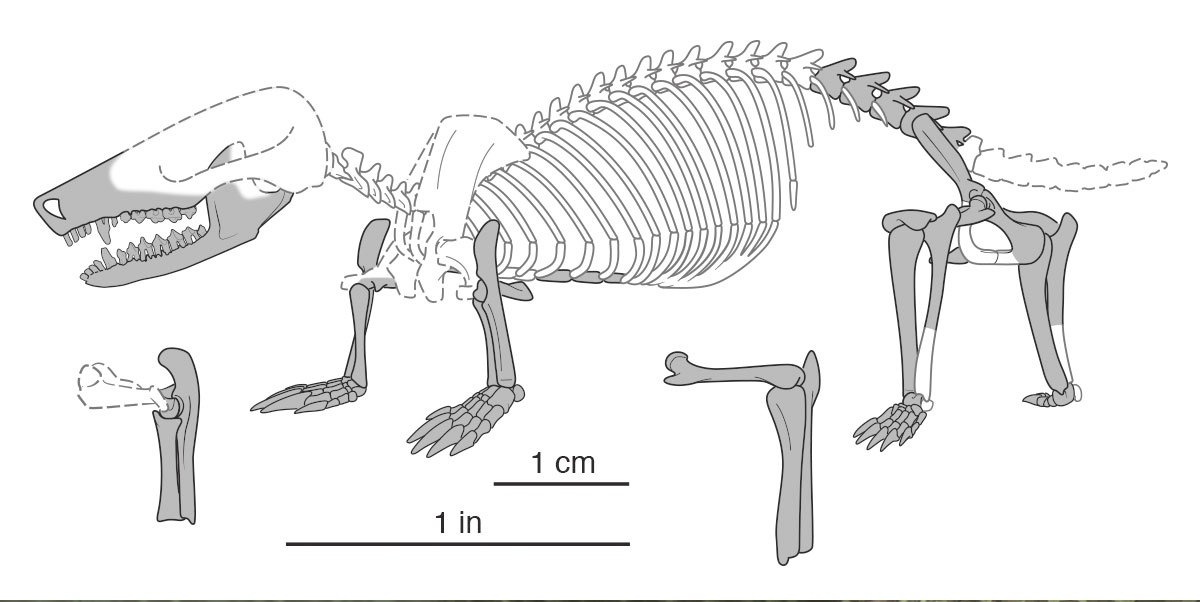

Little skeleton

A skeletal reconstruction of D. brachydactylus revealed a tiny critter, with a skull just 1.7 cm long and a 2.8-inch-long (7 cm) body (skull to rump). The presence of claw bones (oversized terminal phalanges) and large limb bones for its body size suggested this half-ounce (16 grams) pipsqueak was a digger. (Illustration by April I. Neander of the University of Chicago)

The digger

When alive, D. brachydactylus would have taken up residence in burrows along a lakeshore in what is now the Hebei Province. The little guy would have fed on worms and insects in the soil there. Researchers said the lack of one of its finger segments suggests the mammalian creature had a unique embryonic development of its hands and feet. (Illustration by April I. Neander of the University of Chicago)

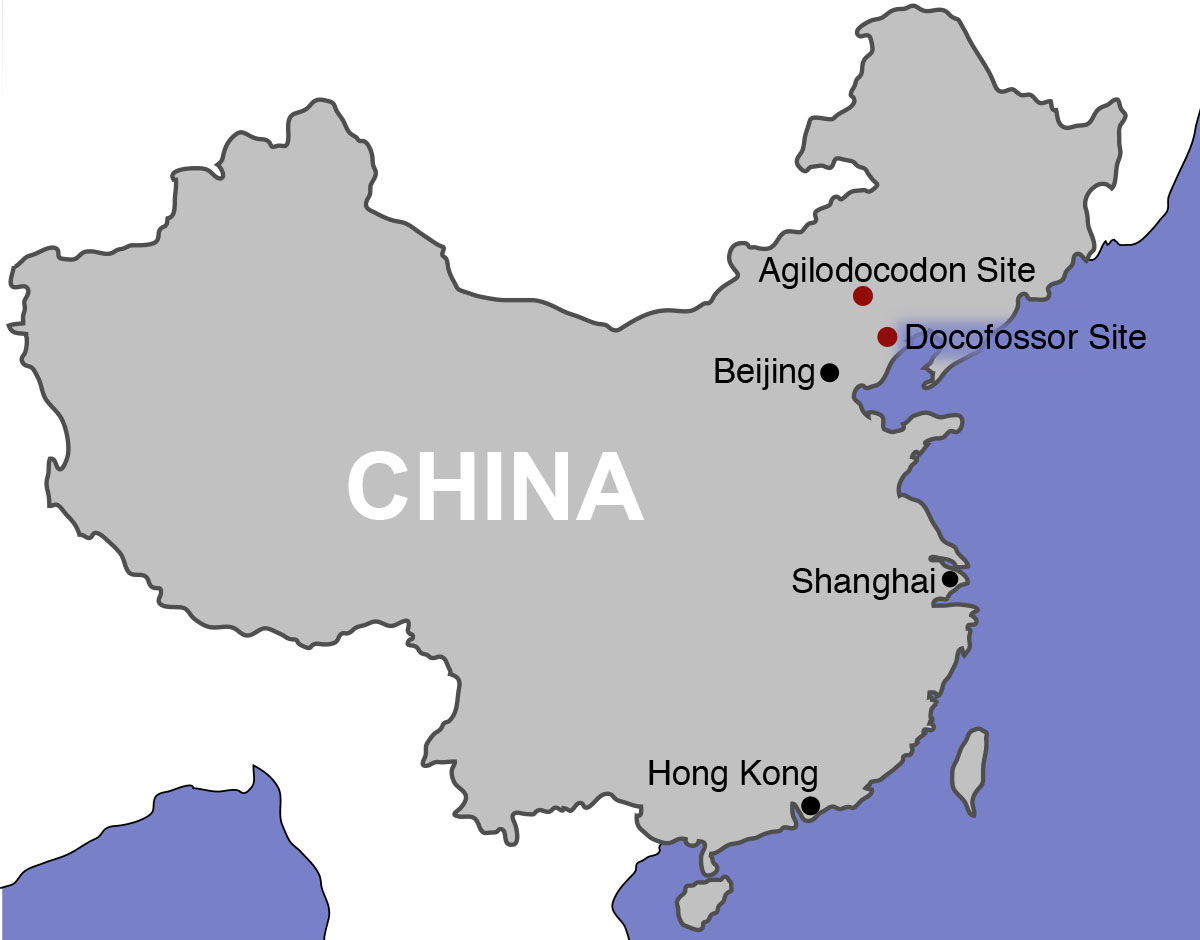

Mammal fossil map

The fossilzed Agilodocodon scansorius specimen came from the Middle Jurassic Daohugou fossil site in Ningcheng County of Inner Mongolia Region of China, while the Docofossor brachydactylus specimen was found in the Late Jurassic Ganggou Fossil Site in Qinglong County of Hebei Province of China. Scientists estimate fossils at the Ganggou Site are about 160 million years old. (Illustration by April I. Neander of the University of Chicago)

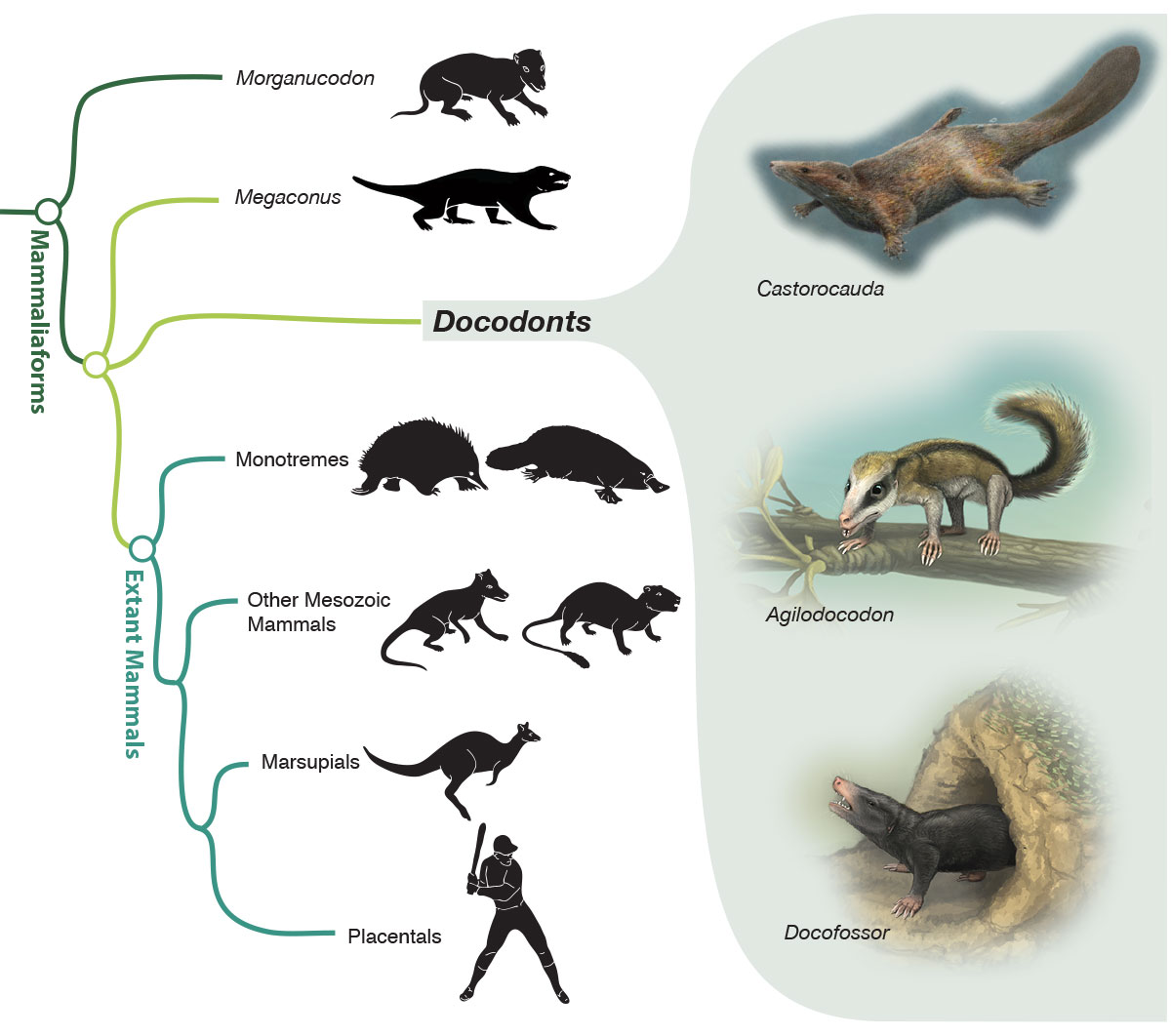

Phylogenetic mammal tree

In this phylogenetic or evolutionary tree, you can see the long-extinct relatives, called stem mammals, of today's mammals. A lineage of the stem mammals, docodonts like those found recently reveal the ecological diversification of the earliest mammals, the researchers say. The new fossils suggest stem mammals had widely diverse feeding and locomotion. (Illustration by April I. Neander of the University of Chicago)

Follow LiveScience @livescience, Facebook & Google+.

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.