Hiding Out of Sight, Are Sharks Self Aware? (Op-Ed)

Ila France Porcher is a self-taught, published ethologist and the author of "The Shark Sessions." A wildlife artist who recorded the behavior of animals she painted, Porcher was intrigued by sharks in Tahiti and launched an intensive study to systematically observe them following the precepts of cognitive ethology. Credited with the discovery of a way to study sharks without killing them, Porcher has been called "the Jane Goodall of sharks" for her documentation of their intelligence in the wild. She contributed this article to Live Science's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

Sharks are smart — and curious. When they sense activity, or prey, in the water, they often go for a look, but they use a variety of tactics to remain hidden.

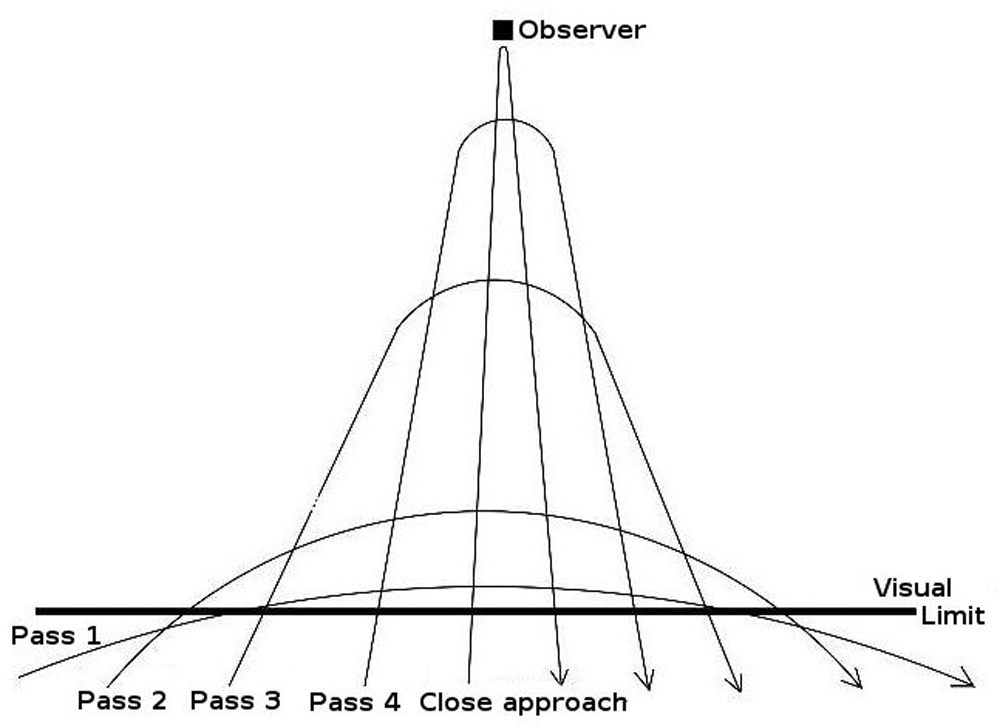

If you are in the water, and a shark becomes aware of you, on its first appearance it comes only briefly into view at the limit of the visual range (the distance at which a view is obscured, from both you and the shark, by particles in the water). Usually a few minutes will pass before the shark circles back, and assuming it's still interested, the shark will pass nearer and approach more directly. It comes closer and closer until it comes directly forward, and either swims close by you, or turns sharply away. Different species and different individuals present variations on this pattern.

Many factors affect the shark's approach, including how curious it is, and how shy. For example, during my ethological study of reef sharks in French Polynesia, young males appeared after sunset in excited bands to mate. They made no stealthy passes — they zoomed straight up to me. But the older females, the biggest and shiest of the sharks, would often linger, listening out of visual range for long periods, and only make one or two cautious passes into view without ever coming near.

This tendency to come and go from beyond visual range as a way to avoid being seen, was typical of the sharks in many circumstances. Their ability to listen and focus on something that is out of their view facilitates this pattern of using the visual limit for concealment.

Avoiding being seen

Sharks will use many tactics to avoid being seen. They will come up behind you for a closer look after appearing once, briefly, in the distance; approach when you put your head above the surface; or pass by you while you are looking the other way. Highly vigilant, they are alert to the moments they can be seen, and when they can act while remaining hidden, and they use this awareness to their advantage.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

For example, during my study I held frequent sunset sessions to which I brought some fish scraps. I was able to check the identities of the sharks swimming in the area, and one elderly black tip reef shark (Carcharhinus melanopterus) was so shy that she passed through each session just once, always when I was watching something in the opposite direction. That implied she had observed me in order to choose the right moment to swim by, and she was good at it, because during the months in which she used this planned approach, she never made a mistake. Pre-occupied with the actions of sharks to my right, I never saw her coming from my left until she had passed and was departing. She glided slowly, barely moving the tip of her tail, always from left to right, 2 meters away and half a meter beneath the surface, always just as it got dark at sunset — it was like a re-run of a movie. [If Sharks Feel Pain, Why Are They Not Better Protected? (Op-Ed)]

Occasionally, as I waited to see the other side of her dorsal fin (so that I could complete her identification for my records), I happened to catch sight of her passing a meter behind me. Had I not turned at that moment, I would have been unaware of her sneaky approach. It took her eight months to join the other sharks, and circle in front of me as they did, so that I could draw the other side of her dorsal fin.

An example involving a different species occurred when an Indo-Pacific lemon shark, Negaprion acutidens, a large individual more than 3 m in length, came to a session. He peeked through the visual limit, like a deer peeking from the forest, until I left the vicinity of my kayak to look around down-current.

That was when he went to investigate my boat, appearing to me as little more than a movement in the water. It was always counter-intuitive that such a large animal, with dentition that resembled rows of two-inch spikes, was afraid of me.

An example of such behavior in another species was a whitetip reef shark, Triaenodon obesus, who had made successive approaches over a period of about ten minutes without coming close. But when I began drawing the dorsal fin patterns of five, new, visiting black tips, he glided in from the side, and passed between my eyes and the slate on which I was drawing.

He seemed to have seen that my attention was fully occupied by something, because he actually glided in front of my eyes as I drew, as if aware that my concentration elsewhere was a shield. By the time I was fully aware of his presence a few centimeters away, the lithe creature was gliding away behind me on the other side. There was no doubt that he felt safe to satisfy his curiosity because he had recognized I was preoccupied.

The sharks I interacted with were vigilant and highly sensitive to attention and eye-gaze. Other ethologists have documented the same phenomenon occurring with terrestrial animals. Recently in 2012, for example, William E. Cooper Jr, reported that lizards are aware of frontal images and slight changes in the movements or postures of the individuals on which they focus.

Heading into hiding

When an animal is aware of the eye-gaze of others, it might decide to hide. Frightened sharks instantaneously vanish beyond the visual range, deliberately hiding.

When I roamed through my study area, its vicinity, and the rest of the lagoon beyond, the resident sharks often followed me, sometimes for hours, while remaining hidden beyond the visual limit. Sometimes, but not always, they would pass briefly into visual range — less than once per hour. It was possible to see who was following me by resting, unmoving, until they glided into view.

This tendency to listen out of view indicated that the sharks were comfortable using their excellent sense of hearing and their lateral-line vibration detector to monitor events that they were unable to see.

The lateral line is found in fish, sharks and some amphibians, and is made up of a series of receptors in a line along the length of the animal. The receptors consist of a sensor within a dome-shaped structure filled with jelly, which is directly affected by pressure in the water, just as the hair cells in human inner ears, which keep us balanced, are directly affected by movement. Researchers believe that the lateral line and the inner ear have a common origin far back in evolutionary time, when life was selecting the basics.

Once the lateral line has recorded vibrations coming in from near and far, then the central nervous system transposes the information into a reasonable facsimile of reality on which the shark can act. As humans, we have no idea of what it would be like to perceive in such a way.

From beyond visual range, sharks can monitor the actions and progress of a person or animal moving in the vicinity — and their willingness to do so for hours at a time seems to indicate an ability to concentrate for long periods. They doubtless also follow other animals for long periods, listening while hidden beyond the visual range.

Waiting and watching

In my studies, when I appeared with another person, the sharks were always curious and suspicious, and on one occasion while snorkelling through the region with my stepson, we were followed by one of the resident sharks, which remained, typically, out of sight. When my stepson walked up onto a dead coral formation to view the surroundings above the surface, the shark instantly glided up to sniff his legs. He was never aware of her, while she seemed to understand that with his face above the surface, he could not see her. By the time he was back underwater (in response to my urgent demands), the shark had vanished into the veiling light.

Sometimes, unexpected events revealed patterns I might not otherwise have seen. When one of the sharks I observed became ill, each evening I tried a different tactic to give him a piece of food in which antibiotics were inserted. The other sharks seemed to anticipate each of my attempts, and their actions made it very difficult for me to medicate him. [Social Sharks (Gallery)]

One of the tactics they used, after several nights of missing out on a treat, was to wait beyond visual range. When the time came, and I went to the kayak and threw the food into the water, seven sharks I thought had left an hour earlier soared in, and the fastest one snatched the treat in mid-water.

From hiding, the sharks had understood the sounds of me getting the treat from the boat and throwing it, and their actions were effective, because one of them did get the food.

Besides providing an example of sharks hiding, their actions reveal their ability to predict something that might occur in the future, and to concentrate on it. Cognition is indicated because the sharks must have referred to a thought about food possibly coming under such circumstances. Then they waited for the signal that would trigger its imminent arrival — concentration on something not present — with the intention of acting on that trigger. Thus, this is also an example of planning and predicting.

Self-awareness

Cognitive ethologist pioneer, the late Donald R. Griffin, formerly of Harvard University, suggested in his book "Animal Minds," (University of Chicago Press, 1994) that when an animal hid itself from view, it was demonstrating self awareness. He described how naturalist Lance Olsen, president of the Great Bear Association, reported grizzly bears seeking places from which they could watch hunters while remaining hidden.

Other early observers such as William Wright (1909) and Enos Abija Mills (1919) reported that grizzly bears tried to avoid leaving tracks. The researchers concluded that these bears were aware of being present and observable, as well as creating effects ― their tracks ― through their movements, which could be seen by others.

The sharks' intentional way of using the visual limit to remain concealed is in the same category, and suggests that sharks, too, are aware of being present and observable, and hence self-aware to that degree.

Follow all of the Expert Voices issues and debates — and become part of the discussion — on Facebook, Twitter and Google+. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This version of the article was originally published on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus