Gem Engraved with Goddess' Image Found Near King Herod's Mausoleum

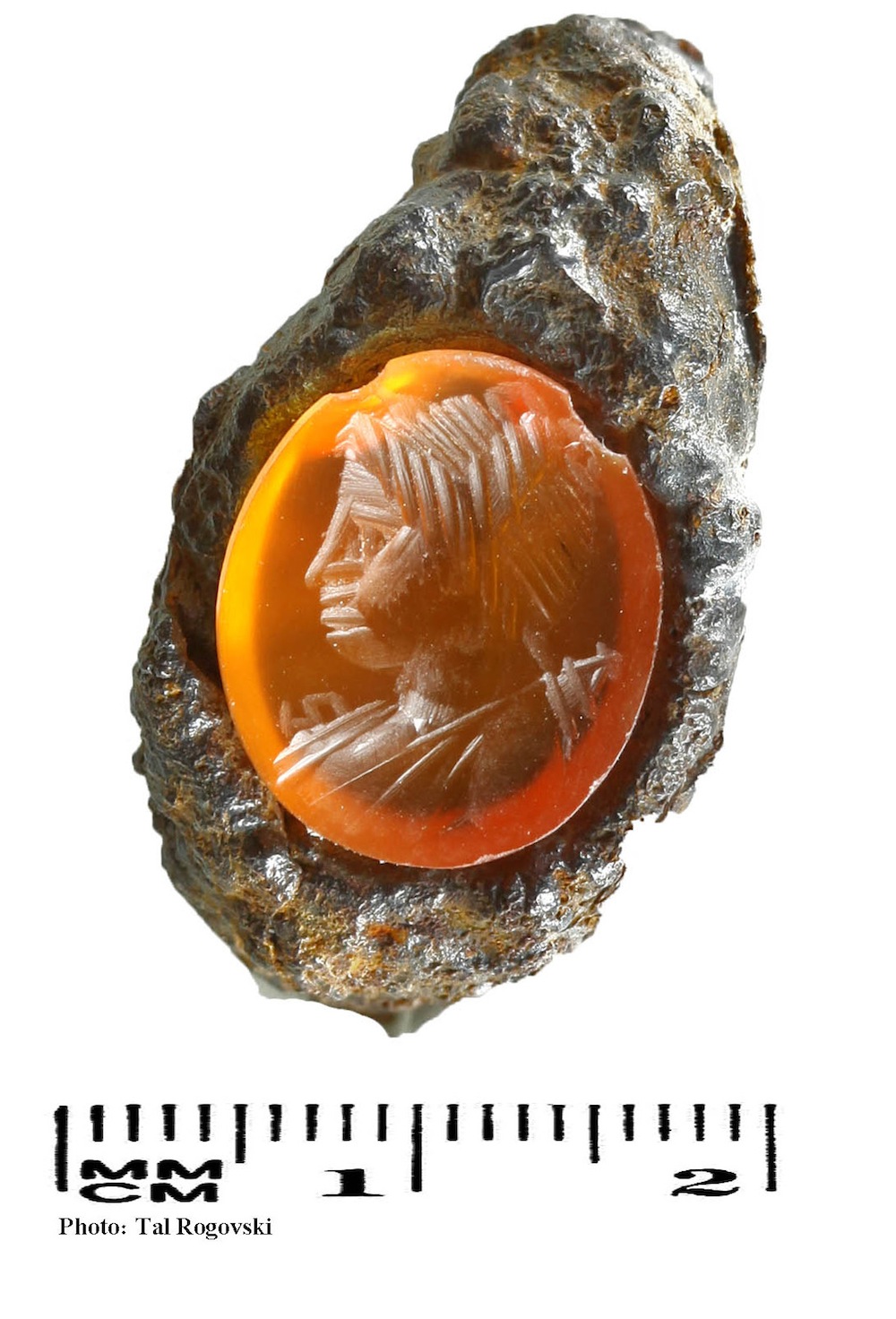

A translucent orange gem engraved with an image of a goddess of hunting has been found near a mausoleum built by Herod the Great, the king of Judea who ruled not long before the time of Jesus.

The carnelian gem shows the goddess Diana (or her Greek equivalent, Artemis) with a sumptuously detailed hairstyle and wearing a sleeveless dress, with a quiver behind her left shoulder and the end of a bow protruding from her right shoulder. Both Diana and Artemis were goddesses of hunting and childbirth.

An iron ring that may have held the gem was found nearby. Researchers say the ring and gem were likely worn by a Roman soldier who was stationed at the site long after Herod's death. The soldier could have used the gem to create seals, pressing it into soft material like clay or beeswax to create images of the goddess, the researchers said. [In Photos: The Controversial 'Tomb of Herod']

Herod, who lived from 73 B.C. to 4 B.C., ruled as king of Judea, with support from the Roman Empire. He constructed a palace complex known as the Herodium about 7.5 miles (12 kilometers) south of Jerusalem. In 2007, archaeologists discovered a hillside mausoleum at the Herodium that may have been the place where Herod was buried. (There is an ongoing debate about whether Herod was actually buried there.)

The ring was found in a garbage dump located above the mausoleum. The dump was used in a cleaning operation by Roman soldiers, who occupied the Herodium after crushing a rebellion in A.D. 71, said Shua Amorai-Stark, a professor at Kaye Academic College of Education in Beersheba, Israel, and Malka Hershkovitz, keeper of antiquities at Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion in Jerusalem.

Researchers cannot be certain that the ring and gem were worn by a Roman soldier, but the idea is bolstered by the fact that the goddess Diana was popular among Roman troops, and the ring itself is fairly large and would have fit an adult male's finger, the researchers said.

Diana "was one of the goddesses appreciated and favored by soldiers, whose power and protection was revered and sought by them," Amorai-Stark and Hershkovitz told Live Science in an email.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The fact that the ring is made of iron also supports the idea that the gem belonged to a soldier, because at the time, most Roman troops could not wear gold rings.

"In the early Roman Empire, ownership of gold rings was restricted to the senatorial and equestrian orders," Amorai-Stark and Hershkovitz wrote, adding that iron rings have been found at other known Roman army sites. [Photos: Gladiators of the Roman Empire]

A goddess's power

The gem likely would have been attached to the iron ring. When the gem was pressed into a soft material, such as clay or beeswax, it left an engraving of the goddess Diana behind.

Gems like this were used throughout the Roman Empire, the researchers said. They could have been used for "sealing correspondence, or confirming wills and contracts of all kinds, as well as for the practical purpose of sealing parcels, purses and so forth," Amorai-Stark and Hershkovitz wrote in the email.

The image may also have had a special significance to its owner, especially if he was a soldier.

"Diana was also believed to protect one from evils of combat," wrote Amorai-Stark and Hershkovitz. "The owner of the gem/ring might have believed in its power to protect him from the evils of war, and war-affiliated hardships and wounds."

Making the gem

A carnelian gem like this one would have been expensive — an item that only people from a wealthy or middle-income background could afford, Amorai-Stark and Hershkovitz said.

Engraving the image of the goddess would have been a challenging job. The "majority of scholars (today) think that the Roman artisans of gems used [a] 'magnifying' glass to engrave the detailed gems with the help of drills," Amorai-Stark and Hershkovitz wrote in the email.

A lubricating powder made from a crushed hard stone would have been applied to the gem before the engraving was done. This powder allowed "fine engraving lines and details" to be added to the gem, while ensuring "that the drilling and the heat produced while engraving does not result in [the gem breaking]" Amorai-Stark and Hershkovitz wrote.

The discovery of the gem and iron ring was published recently in the first volume of the book "Herodium: Final Reports of the 1972-2010 Excavations Directed by Ehud Netzer" (Israel Exploration Society, 2015). Volume 1 focuses on the mausoleum.

Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.