Antarctica's Ice Shelves Are Thinning Fast

Antarctica's floating ice collar is quickly disappearing in the west, a new study reports.

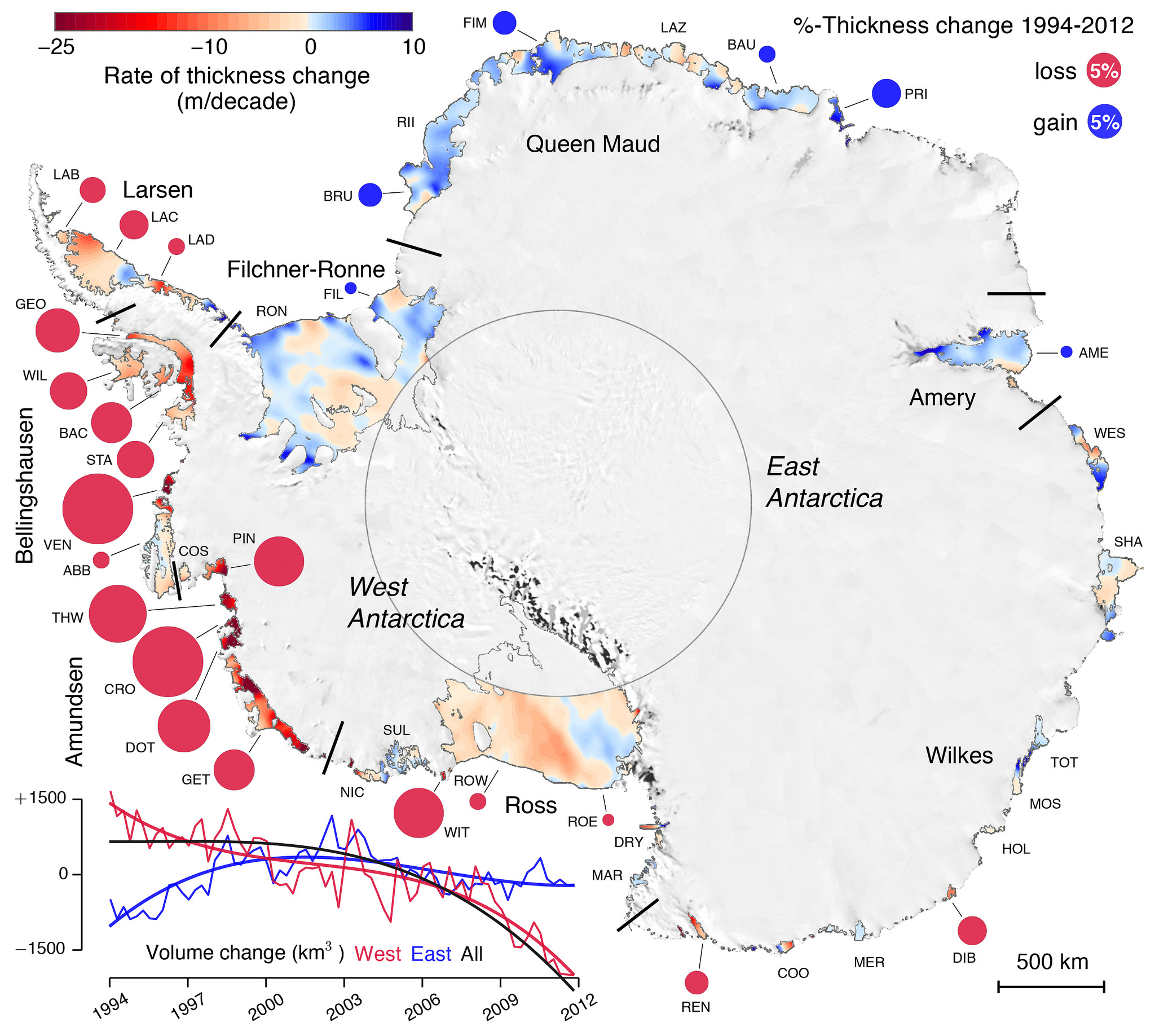

In the Bellingshausen and Amundsen seas — two of West Antarctica's melting hotspots — some ice shelves lost 18 percent of their thickness in the past decade, researchers said. The most dramatic shrinkage occurred in the Bellingshausen Sea's Venable Ice Shelf, which lost ice at an average rate of 118 feet (36 meters) per decade in the past 18 years. At that rate, the entire ice shelf could disappear within a century, said lead study author Fernando Paolo, a graduate student at the University of California, San Diego.

"Some of the ice shelves have persisted for thousands of years, but they can potentially disappear in hundreds of years," Paolo told Live Science.

In East Antarctica, a clear trend has not emerged because there was so much yo-yoing, with individual ice shelves gaining or losing ice from year to year. However, Paolo said that East Antarctica as a whole stopped bulking up in 2003.

"Regardless of any single number, the overall pattern is that West Antarctica has been thinning and the rate of loss has increased, while East Antarctica has stopped gaining mass," Paolo said.

The findings were published Thursday (March 26) in the journal Science.

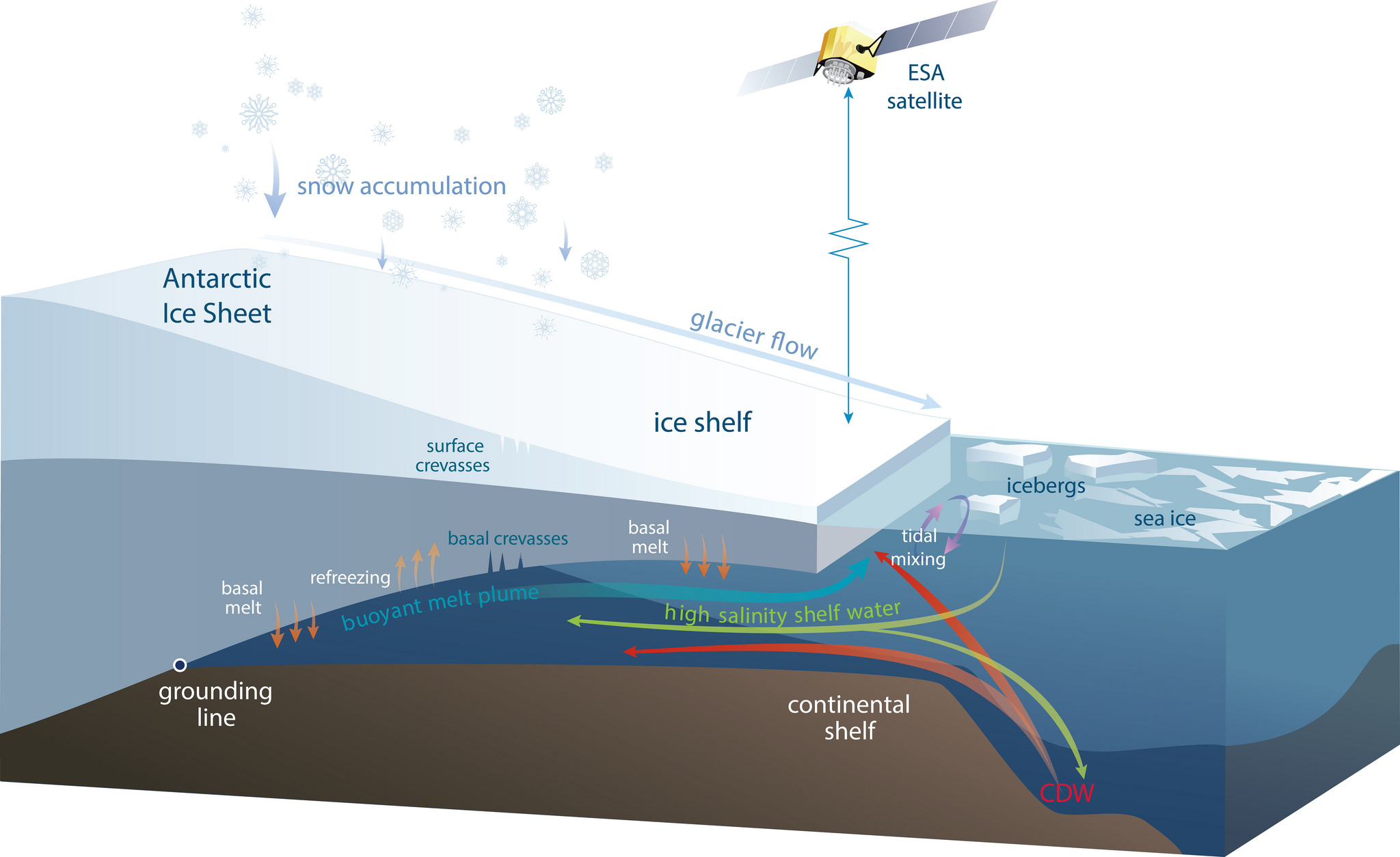

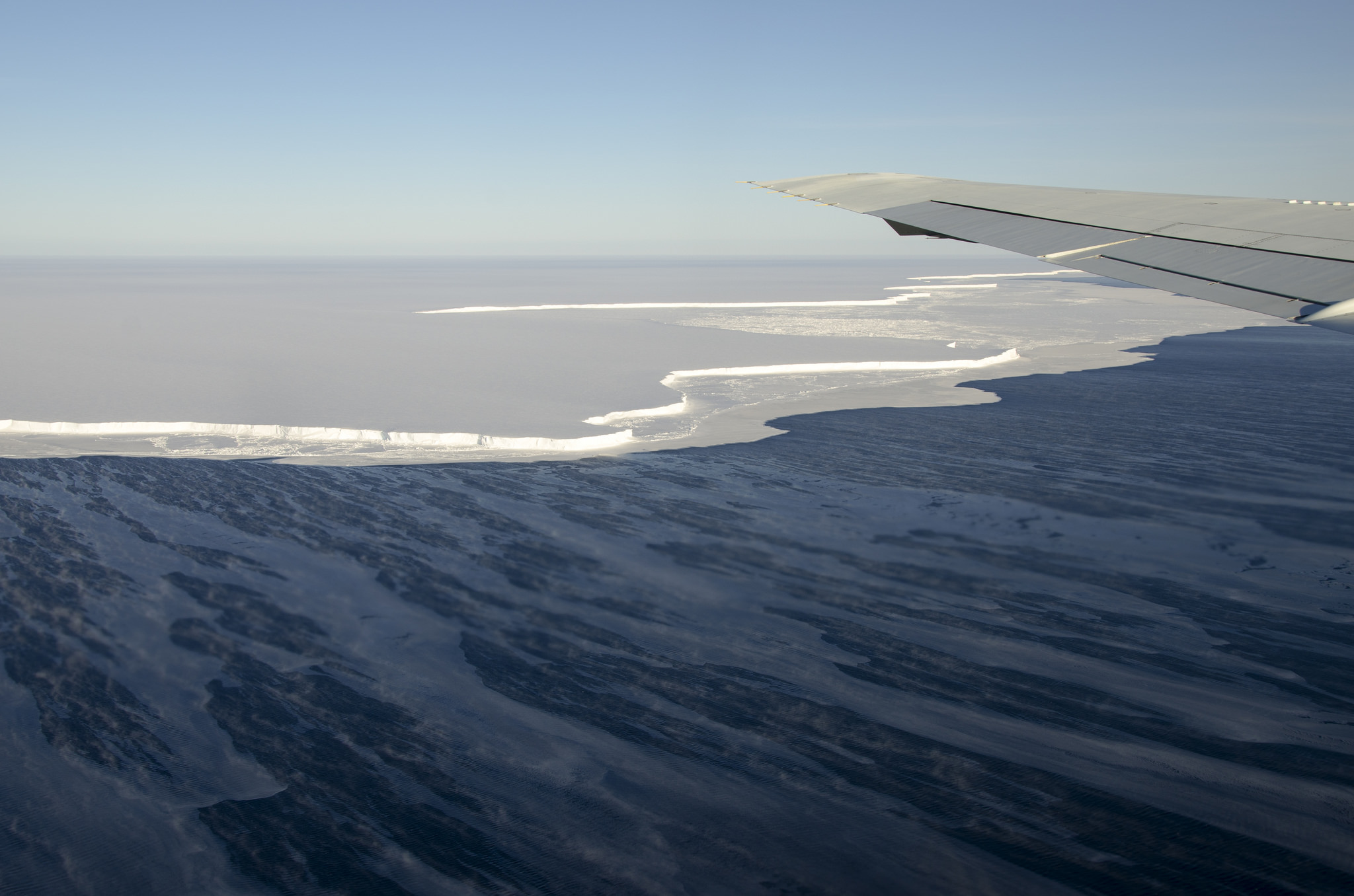

Ice shelves are large, flat pieces of ice attached to glaciers. They form where glaciers flow into the ocean and float long, tonguelike extensions on the ocean. Ice shelves help anchor glaciers by holding back the streaming ice.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

On their own, the ice shelves don't add to sea level rise when they melt. But the collapse of an ice shelf allows the glacier that it was holding back to speed up, dropping more ice into the ocean and accelerating sea level rise. [Photos of Melt: Glaciers Before and After]

Previous work in Antarctica has showed that many ice shelves around the continent are thinning, but the new study is the first to take a comprehensive look at the giant ice patches over time.

"It's a really nice, comprehensive study," said Ian Joughin, a glaciologist at the University of Washington in Seattle, who was not involved in the study.

Paolo assembled an 18-year record of ice changes from three European Space Agency satellites that flew from 1991 to 2012.

Overall, the ice shelves lost little thickness, or volume, between 1994 and 2003, the study found — just about 6 cubic miles (25 cubic kilometers) per year. Paolo said thinning in West Antarctica during that period was offset by ice added in East Antarctica.

But that number jumped sharply between 2003 and 2012, with a 70 percent increase in ice volume loss in West Antarctica, and a small volume loss in East Antarctica. Between 2003 and 2012, West Antarctica lost 74 cubic miles (310 cubic km) of ice every year, the study reported.

The accelerating ice shelf loss is due to warm ocean currents that have encroached on West Antarctica's ice shelves, melting them from below, Paolo said.

The detailed findings match those of previous studies that found the rapid melting of Antarctica's ice shelves, Joughin said. "You can see it's not just some blip," he said. "[West Antarctica] has been thinning pretty steadily the whole time."

Follow Becky Oskin @beckyoskin. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Originally published on Live Science.