How Easter Helped Bring Down a Medical Myth About Ulcers

Some people will celebrate Easter this Sunday. Some scientists, meanwhile, will celebrate the birthday of the humble bacterium Helicobacter pylori.

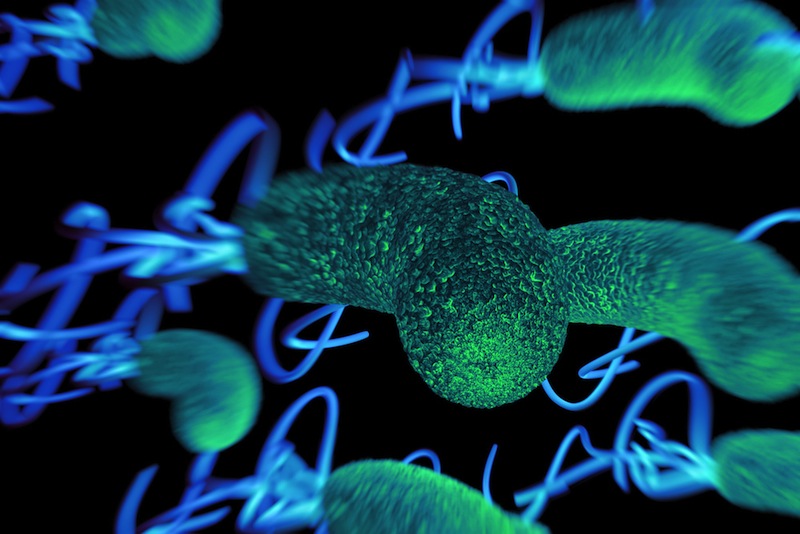

H. pylori infects more than half of the world's population. Many people who carry the bacterium won't ever experience any symptoms of the infection, but it's the culprit behind most ulcers and many cases of stomach cancer — and it hid, unidentified, inside human stomachs for thousands of years.

H. pylori is so old that it followed humans out of Africa. But scientists didn't even know it existed until 33 years ago. Some of them would probably credit Easter with the discovery. [Body Bugs: 5 Surprising Facts About Your Microbiome]

As the story goes, Robin Warren, a pathologist at Royal Perth Hospital in Australia, noticed that half of the biopsies he took from patients with ulcers and stomach cancers contained the spiral-shaped bacterium that would come to be known as H. pylori.

Warren teamed up with Barry Marshall, who was still in training for internal medicine at the time, and they tried to grow H. pylori in the early 1980s — at first, to no avail. They were using the agar dishes typically used for growing Campylobacter, and discarded them after about two days, according to a 2005 article in the journal Cell.

As far as the scientists in the lab were concerned, "Anything that didn't grow in two days didn't exist," Marshall told Discover in 2010. "But Helicobacter is slow-growing, we discovered."

The Easter holiday kept the doctors out of the lab for four days, and when Warren and Marshall returned after the break, they found colonies of H. pylori growing in the lab.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Having an ulcer was once a stigmatized condition, as doctors traditionally believed ulcers were caused by stress, lifestyle choices or spicy foods — and that idea might still persist as a myth today. Marshall and Warren were ridiculed when they suggested that ulcers were actually caused by an infection. But they were able to back up their theory in follow-up experiments, including a famous one in which Marshall infected himself with H. pylori from a patient by drinking a "broth" of the bacteria that caused him to develop gastritis. They later linked the bacterial infection to stomach cancer, too.

In the decades that followed, tens of thousands of academic papers have been published on H. pylori. From analyzing the bacteria's various strains, scientists have been able to test their theories about how humans colonized Pacific islands 30,000 years ago. Recent research has suggested the microbe might have played an evolutionary role in killing off the older people in a population to make way for the young. Remnants of the bacteria have even been discovered in the gastric tissue of 600-year-old Mexican mummies.

The discovery earned Marshall and Warren the 2005 Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine. And now, most peptic ulcers can be cured with a short regimen of antibiotics and acid-reducing drugs.

Follow Megan Gannon on Twitter. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.