A new piece of evidence is reigniting controversy over the potential bones of Jesus of Nazareth.

A bone box inscribed with the phrase "James, son of Joseph, brother of Jesus" is potentially linked to a tomb in Talpiot, Israel, where the bones of people with the names of Jesus' family members are buried, according to a new chemical analysis. Aryeh Shimron, the geologist who conducted the study, claims that because it is so unlikely that this group of biblical names would be found together by chance, the new results suggest the tomb once held the bones of Jesus. Historians place Jesus' birth at some time before 4 B.C. in Nazareth, a small village in Galilee.

"If this is correct, that strengthens the case for the Talpiot or Jesus Family Tomb being indeed the tomb of Jesus of Nazareth," said Shimron, a retired geologist who has studied several archaeological sites in Israel.

If true, the idea that Jesus was buried on Earth would undermine one of the central tenets of Christianity — that Jesus was physically resurrected and rose bodily to heaven after his crucifixion.

But many historians are skeptical. They say the names on the bone boxes (inside the Talpiot tomb) don't all match with those of Jesus' family. In addition, the current research has not been published in a peer-reviewed journal, the experts say. [See Photos of the Controversial Bone Boxes]

Family of Jesus

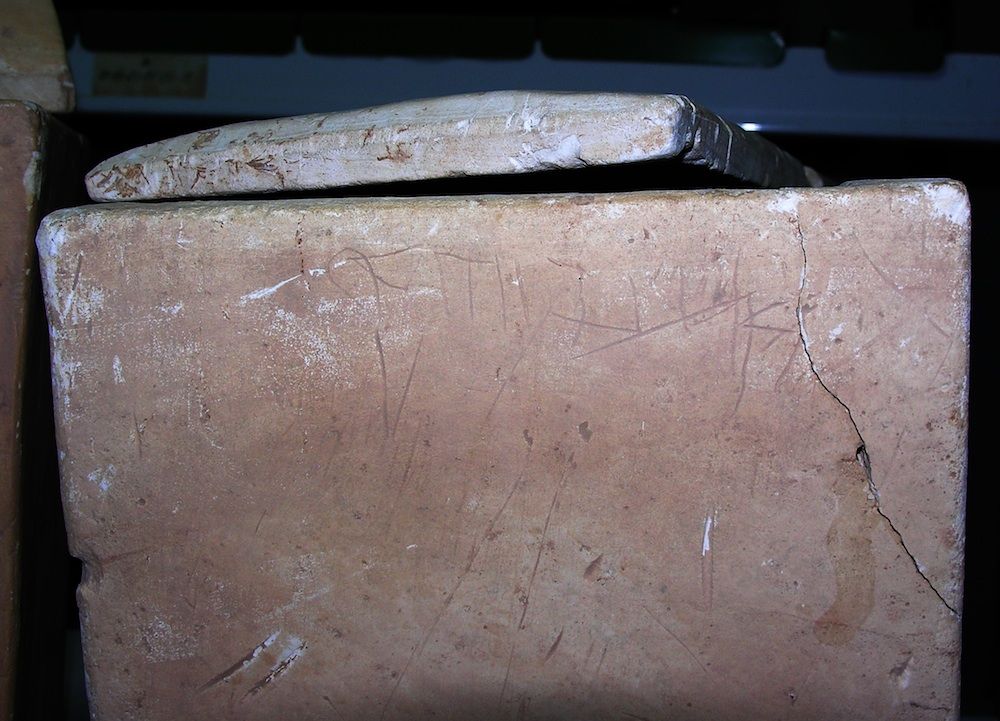

In the time of Jesus, people buried the dead initially in a shroud, but once the flesh had rotted away, they often took the remaining bones and collected them in a small limestone box, called an ossuary, said Mark Goodacre, a New Testament and Christian origins scholar at Duke University in North Carolina who was not involved in the current study. [See Images of the Jonah Ossuary]

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

One of these bone boxes, the James Ossuary, made headlines in 2002, when it was first revealed. The first-century box is inscribed with Aramaic text that translates to "James, son of Joseph, brother of Jesus." If it's authentic, the ancient artifact could potentially be the only known relic from the family of Jesus of Nazareth.

But in 2003, the Israel Antiquities Authority argued that the "brother of Jesus" text was forged, and the collector, Oded Golan, was later tried for fraud. After seven years, an Israeli judge concluded that Golan was not guilty of forgery, in part because Golan produced a photograph of the box sitting on his shelf in 1976, and would therefore have not had an incentive to forge the inscription many years before he went public with the discovery.

Tomb raiders

In 1980, another group of researchers unearthed a first-century tomb in Talpiot, a suburb of Jerusalem. The tomb was flooded with a reddish soil called rendzina, and buried in this soil were 10 boxes, six of which were inscribed with names such as Jesus, Mary, Judah, Joseph and Yose. [Photos: 1st-Century House from Jesus' Hometown]

The tomb came into the public spotlight with the 2007 documentary "The Lost Tomb of Jesus," written by Israeli journalist and filmmaker Simcha Jacobovici, and produced by "Titanic" producer James Cameron. In recent years, Jacobovici has put forward the theory that the James Ossuary came from the Talpiot tomb — and that the tomb was the final resting place of Jesus of Nazareth and his family. But most archaeologists were skeptical of that claim, Goodacre said.

In the new study, Shimron took scrapings from several places on the James Ossuary and the Talpiot tomb ossuaries. He then compared the traces of chemicals — such as aluminum, magnesium, iron and potassium — from those boxes with about 30 to 40 randomly chosen ossuaries collected by the Israel Antiquities Authority. (Some bones were analyzed for DNA but could not be studied thoroughly because they were quickly reburied after excavation, as Jewish law forbids disturbing Jewish burials, Shimron said.)

Shimron found that the chemical signatures from the James Ossuary matched those from the Talpiot bone boxes.

"The flooding of [the] tomb was caused by this earthquake which hit Jerusalem in [A.D.] 363," Shimron told Live Science. "That soil and mud that flooded the tomb also buried the ossuaries."

Because both of the boxes contain chemical signatures associated with this soil, the findings suggest the James Ossuary originally came from the Talpiot tomb, Shimron said.

What's in a name?

If true, the new findings could strengthen the case for the Talpiot tomb containing the bones of Jesus of Nazareth. In this interpretation, after Joseph of Arimathea initially buried Jesus in an empty tomb, his body may have later been laid to rest in this family plot, said James Tabor, a historian at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte, who has worked in the past with Jacobovici, who financed the current research. [8 Alleged Relics of Jesus]

The trouble is proving that the tomb belongs to Jesus of Nazareth and his family, rather than a completely different Jesus. The argument for the former theory rests on statistics — namely, that it would be incredibly unlikely that names associated with Jesus of Nazareth's family would occur by chance for another unrelated Jesus, according to Jacobovici. Adding in another ossuary with names associated with Jesus — namely, the James Ossuary — would potentially buttress that statistical case.

But many experts say that statistical case doesn't hold up. For one, almost all the names in the tomb were common at the time. In addition, some of the inscriptions, such as the name for Jesus, are hard to read, said Robert Cargill, a classics and religious studies professor at the University of Iowa in Ames, who was not involved in the study.

What's more, some of the names found on ossuaries from the tomb have no historical precedent — such as "Judah, son of Jesus."

"There's no evidence at all that Jesus had a son at all, let alone a son called Judah," Goodacre said.

One of the boxes is inscribed with what may be "Mariamne" or, alternatively, "Mary and Mara," Goodacre added. While Jacobovici argues that the name corresponds to one of Jesus' followers, Mary Magdalene, early Christians didn't call Mary Magdalene "Mariamne" — rather, she was just called Mariam or Marya, Goodacre said.

When those inconsistencies are also considered, the statistical case for the names matching those of Jesus' family falls apart, Cargill said.

Jacobovici disagrees with their interpretation of the statistics.

"The fact is that this tomb has more evidence going for it now than probably any other archaeological artifact on the planet. The names are not common and some of the versions of the names are unique e.g., 'Yose' (which corresponds to one of the brothers of Jesus)," Jacobovici said in an email to Live Science.

Debate heats up

Another inconsistency comes in the timing of the discoveries. The James Ossuary was in a collector's hands by 1976, but the tomb wasn't discovered until 1980, Cargill said.

The A.D. 363 earthquake opened up the tomb centuries ago, so it's possible that the box was closer to the entrance of the tomb and was partly visible from the surface, whereas the other boxes were still submerged and hidden. Someone could have seen it and quickly absconded with it, without having discovered the other tombs, Tabor said.

In addition, Tabor argues that, as a Jewish man of his day, Jesus of Nazareth was more likely to be married with kids, rather than celibate. So the mention of Jesus' son Judah is not problematic for their theory, even if Judah were never mentioned in historical documents, Tabor added.

Theological questions

The new findings are incredibly controversial because they deal with one of the most polarizing figures in history — Jesus of Nazareth. Traditional Christians believe that Jesus rose bodily from the dead and ascended to heaven after he was crucified and returned to walk on Earth, Tabor said.

"If you find the bones of Jesus, the resurrection is off," Tabor told Live Science. Conservative Christians "see it as an attack on Christianity and also a refutation of the faith of Christianity."

But Goodacre and Cargill said theological questions don't factor into their skepticism. Rather, the real issue is that the scientific standards have not been met, Cargill said.

Follow Tia Ghose on Twitter and Google+. Follow LiveScience @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Originally published on Live Science.

Tia is the managing editor and was previously a senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.

Most Popular