Stunning images of the mysterious Nazca Lines in Peru

A gallery of images of the Nazca Lines in Peru.

The Nazca Lines, a group of hundreds of mysterious geoglyphs etched into the desert in Peru, have mystified scientists for nearly a century. People from ancient civilizations made the drawings over a period of hundreds of years, beginning around 200 B.C. By analyzing the style and subject matter of the drawings and the methods used to make them, researchers at Yamagata University in Japan have proposed that the lines were made by two different cultures — the Nazca and their predecessors, the Paracas — and were intended to be seen on their respective pilgrimages to an ancient temple, not from the sky as they're more often seen today.

Even today, archaeologists are continuing to discover new Nazca Lines across Peru.

How to see the Nazca Lines

The Nazca Lines were first brought to the world's attention in the 1920s, when airlines brought their passengers over the Nazca Pampa, an arid region of Peru locked between the Andes and the Pacific Ocean. They are best viewed from above.

How were the Nazca Lines made?

Ancient people made the mysterious lines, shapes and drawings by removing the white rocks on the surface of the desert, revealing the reddish earth underneath.

How big are the Nazca Lines?

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The geoglyphs span roughly 85 square miles (220 square kilometers) of the vast desert of Peru. The sizes of the drawings vary.

What was the purpose of the Nazca Lines?

There's still no consensus on why the Nazca Lines were created. Some experts think the drawings were part of a calendar or an ancient irrigation system. Paul Kosok, the late American professor of history and government, once called the geoglyphs "the largest astronomy book in the world," according to Smithsonian Magazine.

Cat

Discovered by archaeologists in 2020, the 121-foot-long (37 m) feline can be seen stretching along a hillside in southern Peru. The enormous drawing, which is reminiscent of a child's doodle, was found during conservation work on the severely eroded hillside. Based on the style of the drawing, with the cat's head facing the viewer, researchers estimate that it dates to sometime between 200 B.C. and 100 B.C. and was made by the Paracas. This ancient culture is well known for including cat depictions in ceramics and textiles.

Condor

There are several geoglyphs inspired by birds, including this condor, which, at 440 feet (134 m) long, is one of the largest works in the desert, according to Nazca Lines Tour.

Monkey

Peru's rainforests are teeming with monkeys, so it's no surprise that ancient artists looked to the local fauna for inspiration. However, Maria Reiche, a German archaeologist and astronomer who studied the Nazca Lines extensively, proposed that the coil-tailed mammal represented the constellation Ursa Major, also known as the "Great Bear," according to The Independent. Over time, experts concluded that the monkey was never used for studying the cosmos, but Reiche's proposal sparked new interest in the geoglyphs.

Spiral

Not all of the lines depict animals. Some form wavy lines, trapezoids and spirals that resemble labyrinths. While labyrinths are often intended to be walked on as a form of meditation, some experts think this geoglyph, in particular, may have been intended as a portal for gods or spirits, Live Science previously reported.

Astronaut lookalike

This geoglyph, which depicts a kind of supernatural being, is one of the best known. It was rediscovered in the 1960s and can be found alongside a collection of other line drawings, including trophy heads and camelids, a group that includes llamas and camels.

Spider

Not all of the geoglyphs have direct meanings. Case in point: the spider. Some researchers think ancient people created this line drawing as a plea for rain, according to National Geographic.

Dog

This drawing depicts a dog with its mouth open and its tail sticking straight up as if on alert. Some researchers think the work depicts a Peruvian Inca Orchid (also known as the naked dog, since it lacks fur), a breed native to Peru.

Not a hummingbird

For years, archaeologists thought the birdlike figure rising from the dust was a hummingbird. However, newer research has determined that the long-beaked creature with outstretched wings was actually a hermit, a bird species that resides in the forests of northern and eastern Peru. These birds are not found in the southern desert where this drawing is located.

Whale

The well-defined flippers and fluke (tail) make it obvious that this drawing shows a whale. The Nazca were particularly enamored with these majestic creatures, often carving their likeness into pottery, according to the American Museum of Natural History.

Human hands

While the vast majority of the Nazca Lines represent animals, a handful resemble human features, including these two hands; one has four fingers and a thumb, and the other lacks a fifth digit.

Sunflower

Despite being created thousands of years ago, the artfully depicted sunflower looks almost modern — at least by hippie standards.

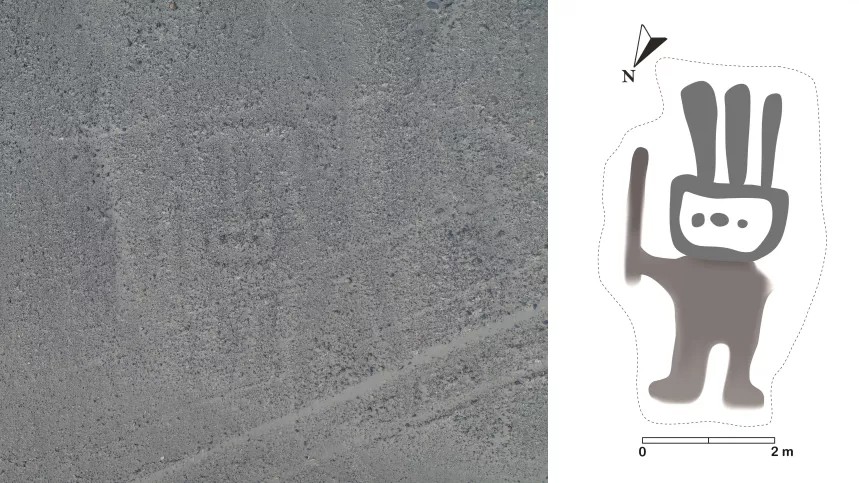

Humanoid

Researchers relied on artificial intelligence to find this humanoid figure, which measures 13.1 feet (4 m) long and 6.6 feet (2 m) wide. After scanning a collection of aerial and satellite images, this machine learning-based method helped point out possible geoglyphs that were otherwise hidden from the naked eye.

Two-headed snake

This horrific image is one of the lines discovered by Japanese researchers in 2019. It illustrates a voracious reptile that's about to devour a human figure.

Macaw

This geoglyph depicts another bird, a macaw, which is found in the Peruvian Amazon rainforest.

Bird

Researchers used AI to find this geoglyph of a bird.

Legs

By using AI, researchers discovered this pair of legs, which is more than 250 feet (77 meters) across.

Fish

This Nazca geoglyph, discovered with AI, depicts a fish that is 62 feet (19 m) across.

Jennifer Nalewicki is former Live Science staff writer and Salt Lake City-based journalist whose work has been featured in The New York Times, Smithsonian Magazine, Scientific American, Popular Mechanics and more. She covers several science topics from planet Earth to paleontology and archaeology to health and culture. Prior to freelancing, Jennifer held an Editor role at Time Inc. Jennifer has a bachelor's degree in Journalism from The University of Texas at Austin.

- Tia GhoseEditor-in-Chief (Premium)