Bawdy Bard: Shakespeare Play's Lost Lines Reveal Sexual Mocking

A lost section of "Love's Labour's Lost," a comedy written by William Shakespeare, has been rediscovered, revealing a song mocking the sexual inadequacy of one of the play's male characters.

The rediscovery of this section did not come from a long-lost manuscript, but rather through the analysis of a mysterious one-word line in the play that has long mystified scholars.

Lovesick Nobleman

Written in the 1590s, the play was performed before Queen Elizabeth I. In the play, a man named Ferdinand, the King of Navarre (in northern Spain), establishes a law banning men in his court from having sex, or even meeting with a woman, for three years while he and his retainers undertake scholarly studies. Ferdinand believes the studies will be more successful if the people around him abstain from sex.

Not long after the law is in place, Costard, one of Ferdinand's subjects, gets caught with a woman named Jaquenetta. Spanish nobleman Don Adriano de Armado — who has a high opinion of himself and his sexual abilities — imprisons Costard. Armado himself falls hopelessly in love with Jaquenetta, freeing Costard on condition that he set Armado up with Jaquenetta. [The 6 Most Tragic Love Stories in History]

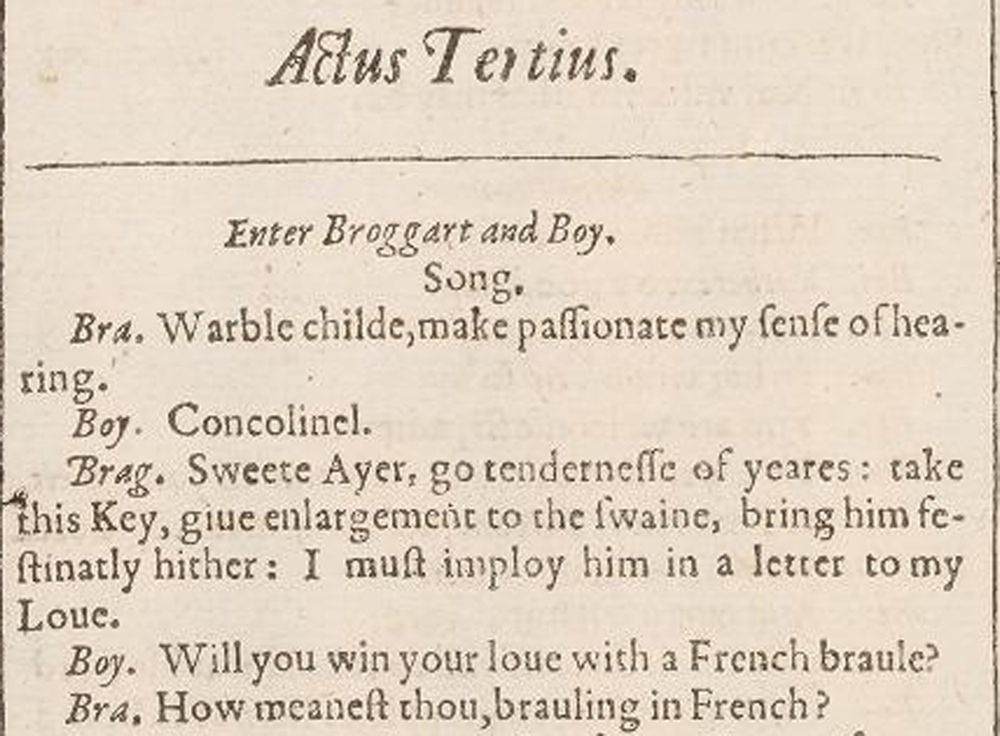

At the beginning of Act III, the lovesick Armado asks his servant, a page named Moth, to "Warble, child; make passionate my sense of hearing."

This is where the mystery begins. When Shakespeare's play was published, the only line that follows is Moth saying the word "Concolinel."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

What Shakespeare meant by "Concolinel" has been a long-standing mystery. The word "song" is written at the start of the third act suggesting Moth is supposed to sing a song related to "Concolinel."

"Moth's solitary word has generally been taken as representing a song, now lost, for which the lyrics are not given in the play," wrote Ross Duffin, a professor at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, in an article recently published in the journal Shakespeare Quarterly.

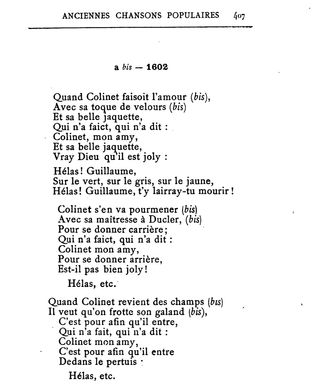

Duffin found that "Concolinel" is actually a misspelling of a French song called Qvand Colinet, which was popular around the time Shakespeare lived. The song refers to a penis that is "too soft and too small," and would have been sung by Moth to mock Armado's sexual inadequacy. Armado, who doesn'tunderstand the song, doesn't realize that his own servant is making fun of him.

"Don Armado was being mocked by the use of this song. He thinks of himself as being so gallant," Duffin told Live Science in an interview. "Don Armado doesn't realize that he's being pilloried, and so that would have been the joke."

The entire song may not have been sung when the play was performed.

Rediscovery

Duffin, a music professor, has written extensively about the songs from Shakespeare's plays, publishing a book about his research in 2004 called "Shakespeare's Songbook."

In his plays, Shakespeare refers to many popular songs in his time, Duffin told Live Science. Some of these songs were so popular their lyrics didn't have to be published.

Part of the problem with the song in "Love's Labour's Lost" is that Shakespeare gave only its name, and those charged with publishing Shakespeare's plays appear to have mangled its French spelling.

Duffin's research revealed several lines of evidence that indicate that this is Shakespeare's lost song. Aside from the similarities in spelling, the song fits in well with the dialogue. Moth is a young servant who regularly finds ways to make fun of his inept master Armado, and this song plays into this tone. [In Photos: Medieval Manuscript Reveals Ghostly Faces]

Also, after Moth sings this song, and Armado asks him to perform a task, Moth asks Armado whether he will win over Jaquenetta with a "French Braule" (braule being a type of song), indicating the song was French.

Additionally, the song lyrics also appear to include the word Jaquenetta. "Without much of a stretch, the repeated line 'Et sa belle iaquette' could be construed as 'And his pretty Jaquenetta,'" wrote Duffin in the article.

Duffin's research indicates this song was popular in Shakespeare's time, and English performers were making their way back and forth from England to the European continent bringing songs back with them.

This song "seems to have been something that was popular probably in the late 16th and in the early 17th century," Duffin said. It was first published as part of an anthology of popular songs in 1602 but would have been known before then.

Duffin found that the song may have been sung to the tune of Sellenger's Round (examples of this tune can be heard on YouTube), but this is uncertain.

Reaction to the discovery

Chantal Schütz, a professor at the Université Sorbonne Nouvelle in Paris, who has published articles on this play, believes the song is likely correct.

"I find the arguments very convincing as concerns the text of the song, and there is ample evidence that songs traveled back and forth between France and England just like other commodities, material or immaterial," she wrote in an email, adding that it may not have been sung to the tune of Sellenger's Round (music for a dance).

It's possible that the newly rediscovered section of the play could be performed as early as this summer at the Stratford Shakespeare Festival in Stratford, Ontario, although this has yet to be confirmed.

Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.