Will Dreadnoughtus Dinosaur Lose Its Heavyweight Title?

Dreadnoughtus — the immense, long-necked dinosaur recently uncovered in Patagonia — may not be as heavy as scientists once thought, a new study suggests.

Instead of weighing a whopping 60 tons, Dreadnoughtus schrani likely weighed between 30 and 40 tons, the researchers who published the new study said, although not everyone agrees on this estimate.

"Using digital modeling and a data set that took in species, alive and dead, we were able to see that the creature couldn't be as large as originally estimated," the study's lead researcher, Karl Bates, a lecturer of musculoskeletal biology at the University of Liverpool in the United Kingdom, said in a statement. [Images: Uncovering the Colossal Dreadnoughtus Dinosaur]

However, Kenneth Lacovara, the paleontologist who discovered the dinosaur, isn't convinced. The model in the new study uses the dinosaur's body volume as a proxy for its mass, said Lacovara, a professor of paleontology and geology at Drexel University in Philadelphia. But Dreadnoughtus' total volume is unknown because scientists have only about 45 percent of the dinosaur's skeleton, he said.

"They're using a proxy that doesn't exist to estimate a number that can never be validated," Lacovara told Live Science.

Carry that weight

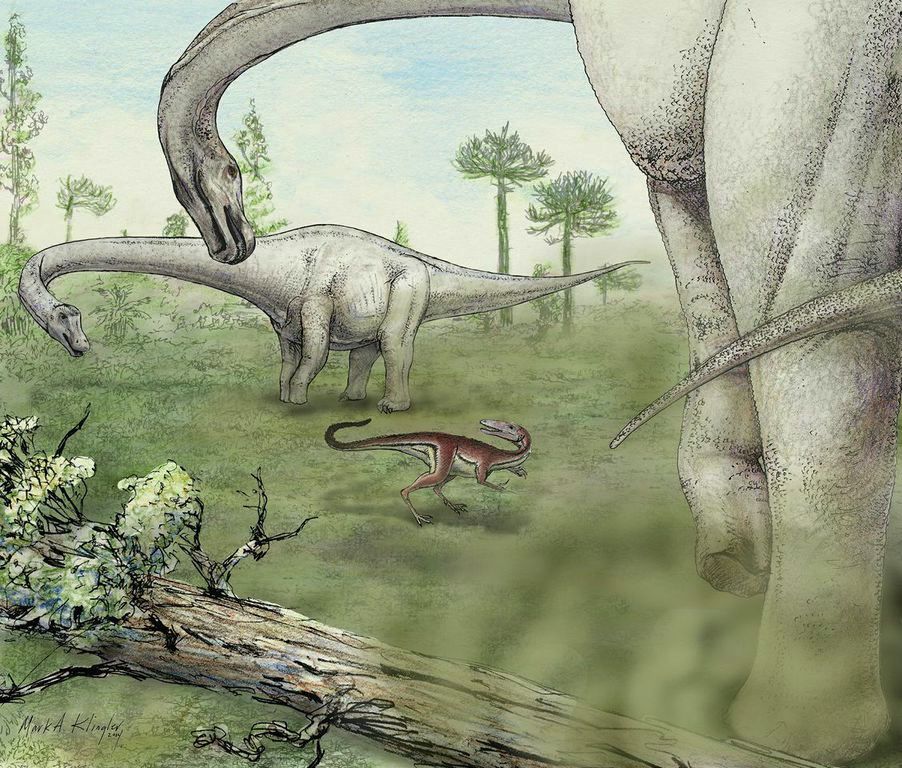

Lacovara and his colleagues published their findings on the 77-million-year-old Dreadnoughtus in 2014. The new species appeared so gigantic and fearsome that Lacovara named it Dreadnoughtus after steel warships. According to the dinosaur's 115 bones (they found a smaller, younger Dreadnoughtus fossil with 30 bones nearby), it likely stood two stories high at its shoulders and measured 85 feet (26 meters) from head to tail.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But some researchers are doubtful of the dinosaur's mass, originally reported to be about 130,700 lbs. (59,300 kilograms). To calculate the animal's mass, Lacovara and his colleagues used a well-known scaling equation based on the circumference of the dinosaur's limb bones. The results made Dreadnoughtus the largest dinosaur with the most complete skeleton on record, the researchers said.

Yet something seemed off, the researchers on the new study said. Two other sauropods (herbivorous, long-necked, four-legged dinosaurs) had similar skeletal proportions to those of Dreadnoughtus, but their calculated masses were less — just 55,000 to 77,000 lbs. (25,000 to 35,000 kg), the researchers on the new study said.

So, they used a 3D skeletal modeling method to get a better idea of Dreadnoughtus' mass. The technique uses a mathematical model to reconstruct the volume of the dinosaur's skin, muscles, fat and other tissues around the bones, they said.

The reconstructed measurements are based on data from living animals, the researchers noted. They explored a range of body sizes to predict how heavy Dreadnoughtus might have been, which is how they reached their 30- to 40-ton estimate.

"The original method used to calculate the mass of the animal is a common one and has been used successfully on many specimens," Bates said in the statement. "The highest estimates produced for this particular giant, however, didn't quite match up."

Dinosaur debate

But Lacovara said the volume-based modeling method isn't appropriate for dinosaurs, especially Dreadnoughtus.

"No one knows whether dinosaur bodies were particularly fat, particularly skinny or somewhere in between," he said. "Also, very little is definitively known about the respiratory system of sauropods. Therefore, no one knows how much volume should be subtracted for the lungs [and] any system of air sacs." [Paleo-Art: Dinosaurs Come to Life in Stunning Illustrations]

However, if researchers were to apply this modeling system to other sauropods, "Dreadnoughtus would still be among the most massive," Lacovara said. He added that if Dreadnoughtus were lighter than originally estimated, the behemoth would have abnormally large legs in comparison to its mass.

"Biomechanists agree that animals essentially have the limbs that they need in terms of weight-bearing capacity," Lacovara said. "In other words, there is no reason to suppose that the limbs of Dreadnoughtus were overbuilt. Proposing that an animal has anomalously huge limbs compared to its mass requires an evolutionary explanation that the authors do not provide."

As for the two sauropods that had similar skeletal proportions to those of Dreadnoughtus — more evidence is needed, Lacovara said.

"A pig and a dog can have similar 'overall skeletal proportions,' but obviously, they would have greatly different weights," he said. "The minimum [bone] shaft circumference of both these animals, however, would show that the pig is actually much heavier."

The new study was published in the June 10 online edition of the journal Biology Letters.

Follow Laura Geggel on Twitter @LauraGeggel. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.