Here's More Proof Earth Is in Its 6th Mass Extinction

Diverse animals across the globe are slipping away and dying as Earth enters its sixth mass extinction, a new study finds.

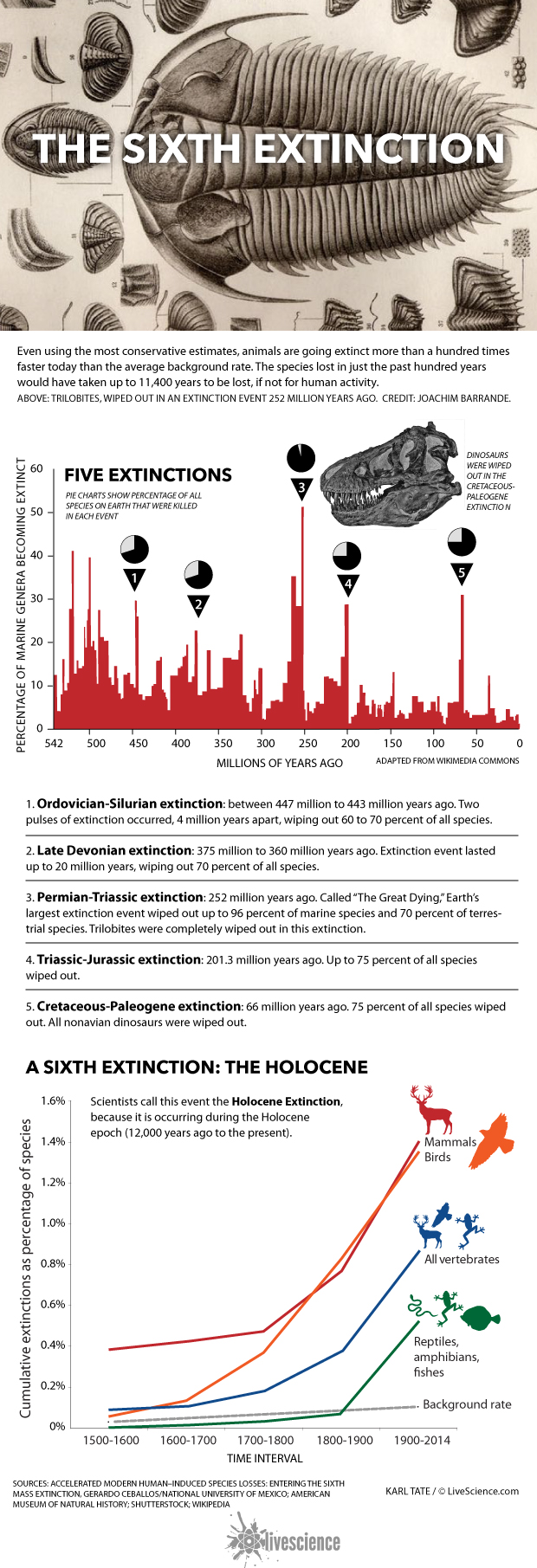

Over the last century, species of vertebrates are dying out up to 114 times faster than they would have without human activity, said the researchers, who used the most conservative estimates to assess extinction rates. That means the number of species that went extinct in the past 100 years would have taken 11,400 years to go extinct under natural extinction rates, the researchers said.

Much of the extinction is due to human activities that lead to pollution, habitat loss, the introduction of invasive species and increased carbon emissions that drive climate change and ocean acidification, the researchers said. [7 Iconic Animals Humans Are Driving to Extinction]

"Our activities are causing a massive loss of species that has no precedent in the history of humanity and few precedents in the history of life on Earth," said lead researcher Gerardo Ceballos, a professor of conservation ecology at the National Autonomous University of Mexico and a visiting professor at Stanford University.

Ceballos said that, ever since he was a child, he struggled to understand why certain animals went extinct. In the new study, he and his colleagues focused on the extinction rates of vertebrates, which include mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians and fishes.

First, they needed to establish how many species go extinct naturally over time. They used data from a 2011 study in the journal Nature showing that typically, the world has two extinctions per 10,000 vertebrate species every 100 years. That study based its estimate on fossil and historical records.

Moreover, that background extinction rate, the researchers found, was higher than that found in other studies, which tend to report half that rate, the researchers said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Then, Ceballos and his colleagues calculated the modern extinction rate. They used data from the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), an international organization that tracks threatened and endangered species. The 2014 IUCN Red List gave them the number of extinct and possibly extinct vertebrate species since 1500.

These lists allowed them to calculate two extinction rates: a highly conservative rate based solely on extinct vertebrates, and a conservative rate based on both extinct and possibly extinct vertebrates, the researchers said.

According to the natural background rate, just nine vertebrate species should have gone extinct since 1900, the researchers found. But, using the conservative, modern rate, 468 more vertebrates have gone extinct during that period, including 69 mammal species, 80 bird species, 24 reptile species, 146 amphibian species and 158 fish species, they said.

Each of these lost species played a role in its ecosystem, whether it was at the top or bottom of the food chain.

"Every time we lose a species, we're eroding the possibilities of Earth to provide us with environmental services," Ceballos told Live Science.

Researchers typically label an event a mass extinction when more than 5 percent of Earth's species goes extinct in a short period of time, geologically speaking. Based on the fossil record, researchers know about five mass extinctions, the last of which happened 65 million years ago, when an asteroid wiped out the nonavian dinosaurs. [Wipe Out: History's Most Mysterious Extinctions]

"[The study] shows without any significant doubt that we are now entering the sixth great mass extinction event," study researcher Paul Ehrlich, a professor of population studies in biology at Stanford University, said in a statement.

Bye-bye, birdie

At this rate, a huge amount of biodiversity will be lost in as little as two to three human lifetimes, Ceballos said. And it can take millions of years for life to recover and repopulate the Earth, he said.

Species make up distinct populations that can spread over a continent. But some vertebrate populations have so few individuals left that they cannot efficiently play their role in the ecosystem, Ceballos said.

For instance, elephant populations are now far and few between. "The same [goes for] lions, cheetah, rhinos, jaguars — you name it," Ceballos said.

"Basically, focusing on a species is good because those are the units of evolution and ecosystem function, but populations are in even worse shape than species," he added.

However, there is still time to save wildlife by working with conservationists and creating animal-friendly public policy, he said.

"Avoiding a true sixth mass extinction will require rapid, greatly intensified efforts to conserve already threatened species, and to alleviate pressures on their populations — notably, habitat loss, over-exploitation for economic gain and climate change," the researchers wrote in the study, published online today (June 19) in the journal Science Advances.

The study supports other findings on Earth's high extinction rate, said Clinton Jenkins, a visiting professor at the Institute of Ecological Research in Brazil, who was not involved with the study.

In 2014, Jenkins and his colleagues published a study in the journal Science that came to the same broad conclusions detailed in the new study, but in last year's study, they also included flowering and cone plants. That study found that current extinction rates are about 1,000 times higher than they would be without human activities.

"This latest study is further evidence of a human-induced mass extinction now underway," Jenkins told Live Science. "Much like the situation with human-caused climate change, years of research have built an enormous scientific case that humanity is driving a mass extinction. What the world’s many species now need are actions to reverse the problem."

Follow Laura Geggel on Twitter @LauraGeggel. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.