Zombie Burials? Ancient Greeks Used Rocks to Keep Bodies in Graves

Ancient supernatural practices may explain why two Grecian graves contain skeletons that are pinned down with heavy objects and rocks, almost as though people wanted to trap the bodies underground, a new article finds.

Archaeologists have known about these two peculiar burials since the 1980s, when they uncovered the graves along with nearly 3,000 others at an ancient Greek necropolis in Sicily. But a new analysis suggests the two graves contained so-called "revenants," dead bodies thought to have the ability to reanimate, leave their graves and harm the living — essentially an ancient version of zombies.

The ancient Greeks believed that, "to prevent them from departing their graves, revenants must be sufficiently 'killed,' which [was] usually achieved by incineration or dismemberment," Carrie Sulosky Weaver wrote in the article, published June 11 in the online magazine Popular Archaeology. "Alternatively, revenants could be trapped in their graves by being tied, staked, flipped onto their stomachs, buried exceptionally deep or pinned with rocks or other heavy objects." [See Photos of the Ancient Greek 'Revenant' Burials]

Sulosky Weaver, a postdoctoral fellow in the department of the history of art and architecture at the University of Pittsburgh, studied the necropolis for part of her forthcoming book, "The Bioarchaeology of Classical Kamarina: Life and Death in Greek Sicily" (University Press of Florida, 2015).

The ancient Greeks colonized Kamarina, a city-state in southeastern Sicily, in 598 B.C., and remained there until the middle of the first century A.D., Sulosky Weaver said. Inhabitants used the city's necropolis, called Passo Marinaro, from the fifth to the third centuries B.C., she added.

About 85 percent of the burials in Passo Marinaro contain intact skeletons that are either lying flat on their backs or on their sides with bent knees, according to reports from Giovanni Di Stefano, one of the site's principal excavators during the 1980s. The remaining 15 percent of the burials are cremations, and about half of the graves contain artifacts, such as terracotta vases, figurines and coins.

Supernatural superstitions

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The two unusual graves immediately caught researchers' attention.

For her book, Sulosky Weaver "needed to understand why these individuals would be buried in a different manner," she told Live Science in an email, during a dig in Turkey.

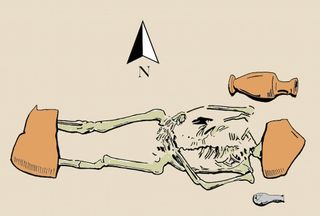

One grave held the skeletal remains of an adult of unknown sex whose teeth had lines of arrested growth — a sign of serious malnutrition or illness, Sulosky Weaver said. The head and feet of the person were covered with "large amphora fragments… a large, two-handled ceramic vessel that was typically used for storing liquids," she wrote in the article.

The heavy amphora fragments "were presumably intended to pin the individual to the grave and prevent it from seeing or rising," she added.

Another grave contains the skeleton of a child, likely age 8 to 13. The skeleton didn't have any signs of disease, but five large stones were placed on top of it, possibly to stop a revenant from leaving the grave, Sulosky Weaver said. [8 Grisly Archaeological Discoveries]

There aren't any known photos of the graves, but Di Stefano drew sketches of each in his journal.

To learn more, Sulosky Weaver surrounded herself with research on supernatural practices among the ancient Greeks. But the Greeks were not alone in their superstitions; other preindustrial societies had similar ways of viewing corpses of certain people, according to the research of folklore historian Paul Barber, she said.

For example, outsiders, illegitimate children, or babies born with abnormalities or on an inauspicious day could be revenants, Sulosky Weaver said. Other candidates included suicides; victims of murder, drowning, plague and curses; and people who were not properly buried, she said. [History's 10 Most Overlooked Mysteries]

The earliest example of revenant burials date to between 4500 and 3800 B.C. in Cyprus, where archaeologists found bodies in graves with millstones pinning down their heads and chests, according to the article.

Another burial uncovered on the Peloponnese Peninsula dating to between 1900 and 1600 B.C. had a large rock over an individual in a stone-built tomb, Sulosky Weaver wrote.

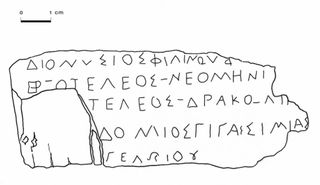

The work of other scholars shows that Greeks living in Kamarina also practiced with "magical" or "curse" tablets called katadesmoi, "so a supernatural explanation for the burials was possible," Sulosky Weaver said.

Katadesmoi are "lead tablets inscribed with petitions, or requests, that would be addressed to underworld deities," she told Live Science. "Usually, the petitioners wanted to gain an advantage in love or business, and it was understood that the deities would direct the spirits of the dead to fulfill the requests of the living. To ensure that the tablets reached the underworld, they would be placed in or near the graves of the recently deceased during secret nighttime ceremonies."

Researchers have found more than 600 katadesmoi from the ancient Greek culture, including 11 from Passo Marinaro, Sulosky Weaver said. Most are degraded and difficult to translate, but some have lists of names, likely of people who were the targets of curses, she said.

Interestingly, a Greco-Roman text dating from between the second century B.C. and the fifth century A.D. tells petitioners to write with ink on seashells to create katadesmoi. Researchers have found three seashells in the Passo Marinaro graves, but it's unclear whether they were intended to serve as katadesmoi, Sulosky Weaver said.

Evidence of these superstitions suggests the ancient Greeks didn't live in fear of the dead, but thought that some dead people could be dangerous or useful to the living, she said.

"Some chose to recruit the dead to achieve specific goals, while others chose to trap potentially dangerous bodies in their graves to keep the living members of the community safe," Sulosky Weaver said. "These activities shed light on some of the lesser-known facets of Greek funerary practice."

Follow Laura Geggel on Twitter @LauraGeggel. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Most Popular