Fourth of July Downer: Fireworks Cause Spike in Air Pollution

Fireworks are a beloved tradition of the Fourth of July, but the colorful displays also bring a spike in air pollution, a new study shows.

The researchers analyzed information from more than 300 air-quality monitoring sites throughout the United States, from 1999 to 2013. The researchers looked at levels of so-called fine particulate matter — tiny particles that can get deep into the lungs, and are linked with a number of health problems.

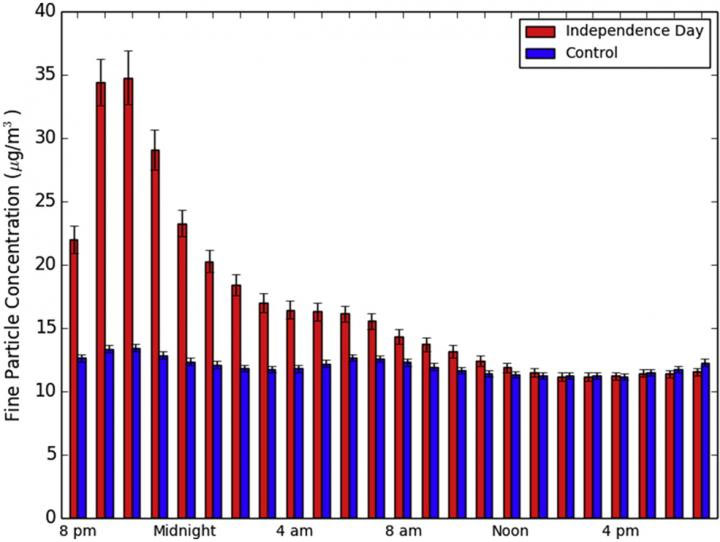

The study found that average concentrations of fine particulate matter, taken over a 24-hour period, are 42 percent greater on July Fourth, compared with the few days before and after the holiday.

The increases in fine particulate matter were highest from 9 p.m. to 10 p.m. on the Fourth. During that hour, fine particulate matter concentrations increased by 21 micrograms per cubic meter (µg/m3), pushing the total concentration close to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency's limit for a 24-hour period of 35 µg/m3. [50 Fabulous 4th of July Facts: History of Independence]

On a local level, increases in fine particulate matter varied depending on a number of factors, including the weather and the proximity of fireworks to the monitoring site. At one site in Utah, where fireworks were set off in a field next to the air-quality monitoring site, particulate matter concentrations rose 370 percent on the holiday, well above the EPA standard.

Exposure to fine particles, like those found in smoke and haze, is linked with a number of negative health effects, such as coughing, wheezing, shortness of breath, asthma attacks and even heart attacks, stroke and early death, according to the EPA. People at greatest risk for problems from fine particulate matter are those with heart or lung disease, older adults and children.

The findings are "another wake-up call for those who may be particularly sensitive to the effects of fine particulate matter," study researcher Dian Seidel, a senior scientist at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's (NOAA) Air Resources Laboratory in College Park, Maryland, said in a statement.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The EPA recommends that people who are sensitive to fine particulate matter try to limit their exposure to fireworks, either by watching them from upwind or as far away as possible.

Although previous studies have noted an increase in fine particulate matter following fireworks displays, the new study is the first to quantify the effects of fireworks nationwide.

"We chose the holiday, not to put a damper on celebrations of America's independence, but because it is the best way to do a nationwide study of the effects of fireworks on air quality," Seidel said. "These results will help improve air-quality predictions, which currently don't account for fireworks as a source of air pollution."

States are allowed to exceed the EPA standard for 24-hour fine particulate matter concentrations, if they can show that the spike was due to fireworks displays, or other "exceptional events," the researchers said.

Follow Rachael Rettner @Rachael Rettner. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.