Alexander the Great's Father Found — Maybe

A decades-old mystery about the body of Alexander the Great's father has been solved, anthropologists claim.

A new analysis of bones from a Macedonian tomb complex reveals a skeleton with a knee injury so severe that it would have caused a noticeable limp in life. This injury matches some historical records of one sustained by Philip II, whose nascent empire Alexander the Great would expand all the way to India.

The skeleton in question, however, is not the one initially thought to be Philip II's — instead, it comes from the tomb next door. The skeletons are the subject of an entrenched debate among experts on ancient Greece and Macedonia. While some praised the new study, others pushed back, suggesting the new research will not quell 40 years of controversy.

"The knee is the clincher," said Maria Liston, an anthropologist at the University of Waterloo, who was not involved in the new study, which is detailed today (July 20) in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS). [See Photos of the Tomb at Vergina and Mysterious 'Philip' Bones]

"This publication in PNAS is incorrect," said Theodore Antikas, a researcher at Aristotle University in Greece and author of another controversial study on bones from the tombs.

A violent history

The story of Philip II is wrought with twists and turns. In 336 B.C., the king was murdered by one of his bodyguards. The motives for the assassination are unclear. Some ancient historians wrote that the murder was an act of revenge stemming from a sordid tale of suicide and sexual assault between Philip II's male lovers and other members of the court.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Whatever the cause, murder was de rigueur for the Macedonian royal family. Within days of Philip II's murder, one of his wives, Olympias — mother of Alexander the Great — let her own homicidal tendencies run free. According to the Latin historian Justin, Olympias killed the newborn daughter of Philip II's newest wife, Cleopatra, in her mother's arms. She then forced Cleopatra to hang herself.

A generation later, after the death of Alexander the Great, the conqueror's half-brother Philip III Arrhidaeus (also spelled Arrhidaios) took the throne. Philip III Arrhidaeus was king in name only, and ancient historians record him as being mentally unfit. His wife, Eurydice, was a warrior, however. She was determined to make her husband more than a figurehead puppet for Alexander's generals, who were by this time vying for power in the void left by his death.

But Philip III Arrhidaeus and Eurydice would lose that battle. In 317 B.C., Olympias came out against them. The couple's troops refused to fight the forces of the mother of Alexander the Great. Olympias had the pair killed and buried. Some months later, they were exhumed and cremated in a display to shore up legitimacy for the next king. [Family Ties: 8 Truly Dysfunctional Royal Families]

Cremation and controversy

Philip II. Cleopatra. Philip III. Eurydice.

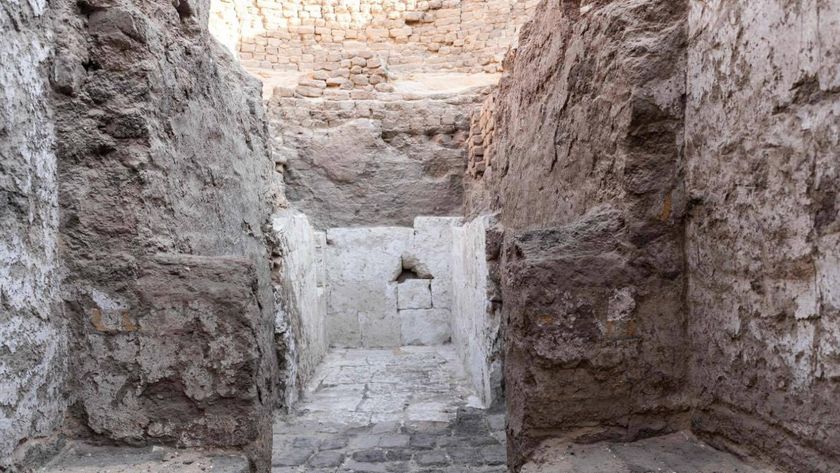

When archaeologists uncovered a Macedonian tomb complex near the Greek city of Vergina in the 1970s, they knew they had royal burials on their hands. But which tombs belonged to which royals?

There are three tombs at the site. Tomb I had been plundered in antiquity but contained human remains and an intricate wall painting of the Rape of Persephone. Tomb II was intact. Inside were the cremated bones of a man and a woman, surrounded by armor and other lavish items. Tomb III is widely accepted to belong to Alexander IV, Alexander the Great's son.

Initially, the bodies in lavish Tomb II were identified as those of Philip II and Cleopatra. But debate has raged over possible injuries to the male skull, over the ages and dating of the skeletons, and over whether the bones were burned with flesh on or off. (As Philip III Arridaeus was cremated long after burial, archaeologists looked for signs that the bones had been burned after the flesh had rotted away.) Many archaeologists suspected the two burned bodies were not Philip II and Cleopatra, but Philip III and Eurydice.

The two sides have been lobbing research papers at each other for years, but seemed at an impasse.

"In fact, the issue has become eminently political, and for years a sort of vendetta has been raging between factions," said historian Miltiades Hatzopoulos of International Hellenic University, who was not involved in the new research.

Now, Antonis Bartsiokas of Democritus University of Thrace in Greece has taken a different tact. Instead of examining the burnt bones in Tomb II, he and his team took a close look at three skeletons from the tomb next door.

The smoking gun

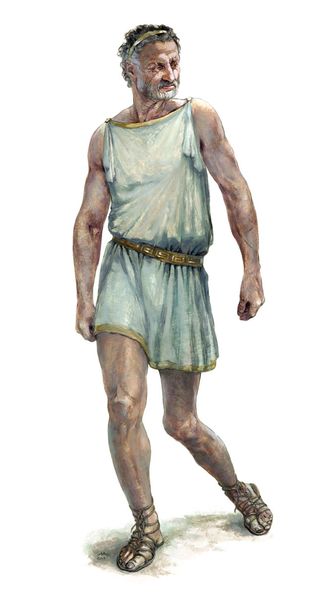

The analysis revealed that the man in Tomb I was in his 40s when he died, and stood 5 feet 9 inches tall (180 centimeters) — impressive for the era. The woman died around 18 years of age, based on measurements of the fusion of her bones. She was about 5 feet 4 inches tall (165 cm). The baby was a newborn, probably only a week to three weeks past the due date.

The ages match historical records of Philip II, Cleopatra and their infant. But the real smoking gun, Liston said, was a knee injury on the male skeleton.

The man's left thigh bone, or femur, had fused with one of his lower leg bones, the tibia. This fusion left the knee joint frozen in place at a 79-degree angle. A hole in the bone suggests the wound was caused by a penetrating injury from a projectile, such as a spear.

And that's where things get exciting. According to historical records, Philip II was injured in the leg during a battle in 345 B.C. He then limped for the rest of his life.

"When I found the femur fused to the tibia at the knee joint, I suddenly remembered the leg injury of Philip, but I could not recall any details," Bartsiokas told Live Science. "I then ran to study the historical evidence."

He found a description of Philip II's wounds in the writings of the ancient historian Justin. "At that moment," he wrote in an email to Live Science, "I knew the bone must belong to Philip!" [Bones With Names: Long-Dead Bodies Archaeologists Have Identified]

The injury does match descriptions of Philip II's limp, the University of Waterloo's Liston said.

"This was a devastating injury that separated the knee joint and left it probably completely unstable until it fused," Liston told Live Science. The pain would have been excruciating, she said.

After reading the new PNAS paper, she said, she asked two middle-age men at her lab in Athens to stand on one foot, with the toes of the other foot just touching the ground. The angles of their knees were 72 degrees and 80 degrees. This ad hoc experiment suggests that, like Philip II, the man in the tomb could have walked, but only with difficulty. He probably could have ridden a horse — but he may have been vulnerable in hand-to-hand combat.

"This injury may also explain why Philip, a skilled warrior, was so utterly unable to fight off the assassins," Liston said. "With this knee, he would have limited mobility and very poor balance."

An end to controversy?

If Philip II and his wife and baby occupy Tomb I, it stands to reason that Philip III and his wife are the contested skeletons in Tomb II, Bartsiokas and his colleagues write today (July 20) in PNAS. [See Images of the Tomb II and Bones Inside]

Whether the finding will rewrite history remains to be seen. The museum at the site of the Royal Tombs of Vergina identifies Tomb II, not Tomb I, as belonging to Philip II. So does UNESCO, which classifies the monuments as a royal heritage site.

"These are bold claims that I don't think will be very welcome in certain quarters in Greece," said Jonathan Musgrave, an anatomist at the University of Bristol, who has argued that the bones in Tomb II belong to Philip II and Cleopatra.

Indeed, researchers who have argued for Tomb II as Philip II's final resting place were not quickly convinced by the new study. In 2014, two bags of human and animal bones were found in a storage area with plaster from Tomb I, Antikas told Live Science. He and his team have analyzed those bones, he said, and found that Tomb I contained not two adults and a baby as discussed in Bartsiokas' new paper, but two adults, a teenager, a fetus and three newborns. Those findings have yet to be published in a peer-reviewed journal, pending permission for further study from Greece's Central Archaeological Council, Antikas said.

"Any prejudgment concerning the occupants is impossible before the complete context is re-examined," said Chrysoula Paliadeli, an archaeologist at the director of the Aristotle University excavations at Vergina.

Even the "smoking gun" leg wound falls under scrutiny; ancient historians were not always very detailed or clear with their sourcing. Bartsiokas and his team trust the writings of Demosthenes, a contemporary of Philip II, who simply wrote that the king was wounded in his leg. But 300 years later historian Didymos wrote that Philip's wound was in his right thigh, said Hatzopoulos of International Hellenic University. The wound on the skeleton analyzed by Bartsiokas was on the left leg.

It might seem natural to trust the historian who was writing at the time of Philip II's life versus the one writing 300 years later, but Didymos' source was probably Theopompos, who did live at the same time as Philip II, Hatzopoulos said.

"Having followed this controversy through four decades I have come to the conclusion that in this particular issue one cannot put much faith in the so-called 'exact sciences,'" Hatzopoulos said. "Reputed scientists have contradicted one another time and time again."

Bartsiokas and his team seemed prepared for ongoing strife.

"I think that we have made a very strong case," said study co-author Juan-Luis Arsuaga of the Universidad Complutense de Madrid. "Now the focus of attention will turn to Tomb I. I am open to debate."

Editor's Note: This article was updated to correct a mention of Desmothenes that should be Didymos.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitterand Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook& Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.