The long-lost palace of Sparta, one of the most famous civilizations in ancient Greece, may have been discovered. Archeologists have unearthed a 10-room palace holding cultic objects and clay tablets written in a lost script. Here's a look at the remains of the Sparta temple and striking artifacts.

Palace ruins

The floor of a room in the remains of the Spartan palace that burnt to the ground in the 14th century B.C. The ten-room palace is likely the lost palace of Sparta. History and other written artifacts such as Homer's epics, reveal that during the Mycenaean period, Sparta was a flourishing culture. Yet no palace had been found from that time period until now. (Photo Credit: Greek Culture of Ministry)

Palatial tablet?

Researchers found a file artifact within the remains of the possible Spartan temple. The site was home to many clay tablets written in Linear B, an early form of ancient Greek that was used for administrative purposes. The team has deciphered a few words on the clay tablets so far and names, some religious elements, and records for financial transactions appear. (Photo Credit: Greek Ministry of Culture)

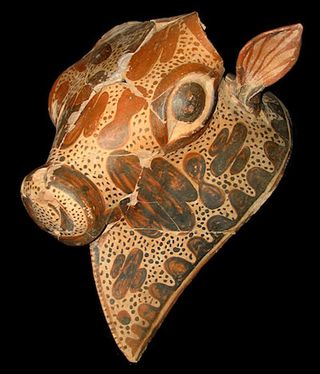

Bull's head

Scientists also investigated a second structure on the ancient Greek site, which preserved fragments of ancient murals. In addition, a sanctuary east of the courtyard at this site held various cultic religious objects, including ivory idols and figurines, a rhyton, or drinking vessel, with a bull's head on it (shown here), large newts and decorative gems. (Photo Credit: Greek Ministry of Culture)

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

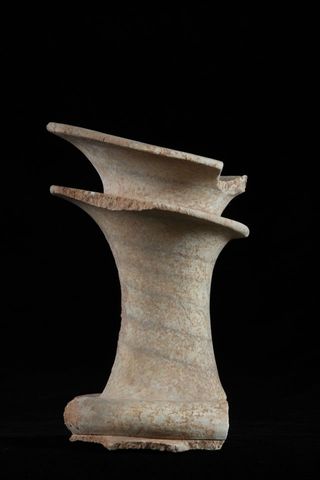

Temple drinks

Here, the neck stone of a ritual jug found at the ancient Greek site. The fact that both religious and administrative objects were found at the site point to it being a very significant place in the Bronze Age.

Nautilus detail

A seal depicting a nautilus was found at the ancient Greek palace, researchers say. (Photo Credit: Greek Ministry of Culture)

Digging up the holy past

This photo shows part of the excavation at the site in ancient Greece. It could take years for researchers to excavate the entire site, which was first discovered in 2009. To avoid damaging the valuable olive trees that dot the landscape, researchers are excavating trenches that are carefully placed to avoid the trees. (Photo Credit: Greek Ministry of Culture)

Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+.

Tia is the managing editor and was previously a senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.

Most Popular