How Armored Dinosaur Got Its Bone-Bashing Tail

Armored, squat, and built like a tank, ankylosaurs were a type of dinosaur known for their bony, protective exterior and distinct, sledgehammer-shaped tails. Now, scientists have pieced together how the animals' rear-end weapons evolved, finding that the hammer's "handle" came first.

Ankylosaurs were a group of bulky, tanklike dinosaurs with bony plates covering much of their bodies. Some of these animals — a subgroup known as ankylosaurids — also came equipped with a weaponized tail club as well.

"Ankylosaur tail clubs are made of two parts of the body," said study lead author Victoria Arbour, a postdoctoral researcher in the Department of Biological Sciences at North Carolina State University and the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences. "They're made of the bones of the tail — the vertebrae — that change so that they’re stiff and lock together in a really characteristic way. We call that the handle, like the handle of an ax. And the other part of the tail is the knob." [Paleo-Art: Dinos Come to Life in Stunning Illustrations]

The knob, or the large ball-type object at the end of the tail, was made of special bones called osteoderms, which actually formed in the skin, the researchers said.

Arbour was interested in examining what part of this weapon evolved first. Was it the handle or the knob? Or did they develop at the same time? "So as I was looking at ankylosaur fossils, for lots of different projects, I always kept an eye out for any evidence for some of those structures. Especially in older specimens I was looking at," she told Live Science.

One of the fossils that caught Arbour's interest was the Gobisaurus, an ankylosaur that lived in Asia about 90 million years ago. The Gobisaurus' tail bones were fused and locked into a complete handle, but there was no knob at the end of its tail.

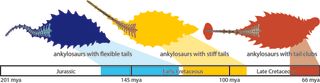

This provided a clue about the weapon's evolution, the researchers said. By comparing Gobisaurus with many other ankylosaur species and working them into a timeline, Arbour was able to show that the tails evolved handle-first. The researchers also used computer software to create a kind of family tree of ankylosaurs, which supported their findings.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

This suggests that ankylosaurs started developing stiff tails as early as 120 million years ago. The knob was a more recent feature and didn't show up until about 75 million years ago, the researchers said.

The knob would have been a formidable weapon. It could grow to be 24 inches (60 centimeters) wide in some ankylosaur species, and would have been very heavy. A 2009 study by Arbour, published in the journal PLOS ONE, estimated that large ankylosaurs could even fracture bones with their club tails.

But even without the knob, an ankylosaur's tail would have packed a wallop, according to the researchers. "Having a stiff tail is still kind of like having a baseball bat," Arbour said. "If someone hits you with a baseball bat, that’s still really going to hurt, even if it doesn't have an ax head on it."

Next, the scientists want to investigate why the animals evolved tail clubs in the first place. Did they evolve to fight off predators? Or was it a way to compete for territory and mates? And why aren't tail weapons more common in other kinds of animal?

"I think it's important to know about why we see the things in nature that are there," Arbour said, "And I think it's cool to understand how things have evolved, why they're evolving, and understand what has shaped the world around us today."

"[W]e don't have anything like [ankylosaurs] today," she added. "It’s interesting to think about why we don't see any animals with that sort of body shape and body plan."

The new study was published online Aug. 31 in the Journal of Anatomy.

Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Most Popular