Frozen Giant Virus Still Infectious After 30,000 Years

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

It's 30,000 years old and still ticking: A giant virus recently discovered deep in the Siberian permafrost reveals that huge ancient viruses are much more diverse than scientists had ever known.

They're also potentially infectious if thawed from their Siberian deep freeze, though they pose no danger to humans, said Chantal Abergel, a scientist at the National Center for Scientific Research at Aix-Marseille University in France and co-author of a new study announcing the discovery of the new virus. As the globe warms and the region thaws, mining and drilling will likely penetrate previously inaccessible areas, Abergel said.

"Safety precautions should be taken when moving that amount of frozen earth," she told Live Science. (Though viruses can't be said to be "alive," the Siberian virus is functional and capable of infecting its host.)

Article continues belowDiscovering giants

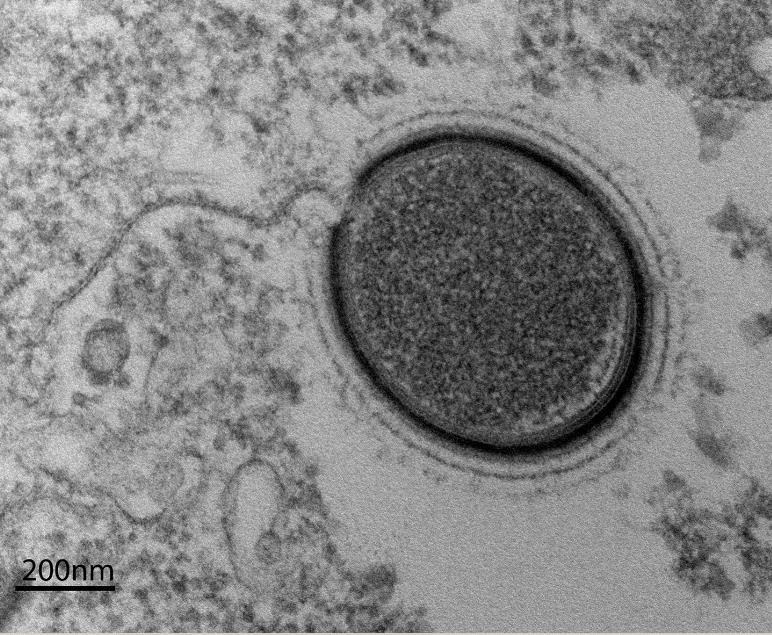

The new virus isn't a threat to humans; it infected single-celled amoebas during the Upper Paleolithic, or late Stone Age. Dubbed Mollivirus sibericum, the virus was found in a soil sample from about 98 feet (30 meters) below the surface. [The 9 Deadliest Viruses on Earth]

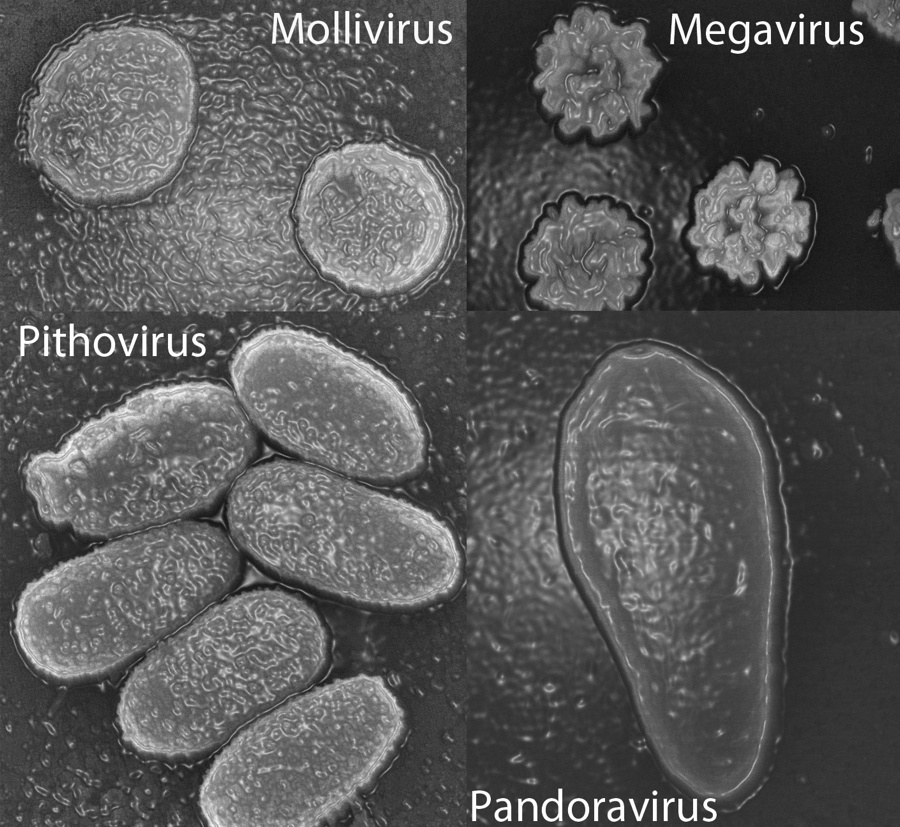

M. sibericum is a member of a new viral family, the fourth such family ever found. Until about a decade ago, viruses were thought of as universally tiny, Abergel said, and they were isolated by filtration techniques that strained out larger particles. But after the discovery of an amoeba-infecting giant virus called Mimivirus, first reported in the journal Science in 2003, researchers widened their search for bigger viruses. Mimivirus and its ilk are so large that they can be seen under an ordinary light microscope. The largest of this group, Megavirus chilensis, has a diameter of about 500 nanometers. Typical viruses range in size from 20 nanometers up to a few hundred nanometers.

Since the discovery of the Mimivirus family, researchers have discovered the Pandoraviridae and Pithoviridae families — the latter discovered in the same soil sample as M. sibericum and reported by Abergel and her colleague Jean-Michel Claverie, the head of the Structural and Genomic Information Laboratory at the National Center for Scientific Research at Aix-Marseille University, in 2014.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Unusual evolution

M. sibericum is wider in diameter than the other giant viruses discovered, at 600 nanometers versus 500. It has a genome of 600,000 base pairs (picture the "rungs" on the DNA "ladder"), which hold the genetic instructions to create 500 proteins. Viruses are snippets of RNA or DNA that work by hijacking a cell's machinery to carry out these instructions. [Tiny Grandeur: Stunning Images of the Very Small]

Abergel and her team are interested in studying resurrected giant viruses to understand how this group evolved and how viral genetics could have influenced the evolution of cells. Viruses are incorporated into cells, and viral DNA sometimes becomes a permanent part of a cell's genome.

"Viruses played a role in making the cell evolve in a very good way," Abergel said. The researchers don't know when giant viruses emerged on Earth, but they probably have roots in the very origins of DNA and RNA, she said.

"We are now at the stage where there are four families of giant viruses, and we can say that they are much more diverse [than previously known]," Abergel said.

The researchers' technique to isolate and study these viruses doesn't pose a threat to humans or animals, Abergel said, but it's possible that dangerous viruses do lurk in suspended animation deep belowground, she said. These viruses are buried deep, so it's likely that only human activities — such as mining and drilling for minerals, oil and natural gas — would disturb them. The discoveries of the giant viruses reveal that they can remain infectious for at least tens of thousands of years, Abergel said. So far, however, scientists have yet to discovery any ancient human-infecting giant viruses.

Deeper study of the viruses will help clarify the risk, Abergel and Claverie wrote in a statement in 2014. But the research has the potential to answer basic questions as well, Abergel said.

"We do think that these giant viruses will help us understand how life appeared on Earth," she said. "We think there are so many genes which are unique to those genomes, and there are many things to learn from the study of those genes."

The research appeared online Sept. 8 in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus