Adrian Robinson Jr., a professional football player who died by suicide earlier this year, had a brain disease, his autopsy recently revealed. The same disorder has also been found in others who have sustained repeated blows to the head.

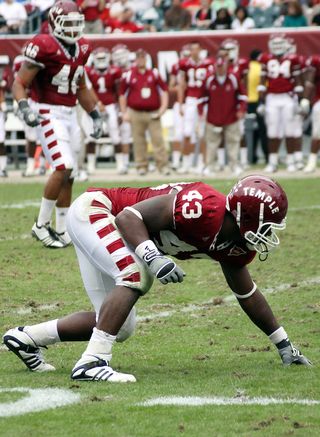

Robinson, who played for several football teams, including the Tampa Bay Buccaneers and the Pittsburgh Steelers, died on May 16. During his two years in the National Football League (NFL), he suffered several concussions.

Now, an autopsy revealed that he had signs of a chronic brain disease called chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE).

"He went from being one of the nicest guys you'd ever want to talk to, to having a darker edge at times," Ben Andreozzi, the lawyer for Robinson's family, told ESPN. "The family started noticing changes in his behavior and didn't know why."

Although the degenerative brain disease that Robinson had has gained increasing visibility in recent years, people may not know exactly what CTE is, or who is at greatest risk of developing the disorder. [6 Foods That Are Good for Your Brain]

Causes of the disease

CTE, which was traditionally associated with boxers, arises after repeated blows to the head cause brain injury. The disease can cause symptoms such as difficulty learning, memory loss, impaired executive function, depression and suicidal thoughts.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In a person with CTE, the brain injuries lead to the release of an abnormal protein known as tau, which gradually builds up in the brain and damages brain cells. Similar proteins are found in the brains of Alzheimer's patients. However, in people with CTE, tau builds up in the troughs of the wrinkly surface of the brain, whereas in people with Alzheimer's, the protein is more evenly spread out, and found in deeper tissue.

Today, the disease is perhaps most closely associated with football players, but recent research suggests that hockey players, wrestlers, soldiers, and even people who participate in lower-impact sports such as soccer and rugby can also develop the disease.

In the last few years, a string of high-profile suicides have called greater attention to the brain disease. In 2011, Dave Duerson, a retired NFL football player, shot himself in the chest, and in his final note to family asked that his brain tissue could be examined for the disease. An autopsy revealed signs of CTE in his brain. Junior Seau, another former NFL star who committed suicide, also had CTE.

A 2012 study in the journal Neurology found that NFL players had four times the risk of dying from Alzheimer's disease or amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (also called ALS, or Lou Gehrig's disease) compared to the general population. However, the researchers noted, it's possible that CTE was the true cause of death in those players found to have Alzheimer's or ALS. The researchers relied on death certificates, rather than autopsy, so there was no way to know for sure, the authors wrote.

Future research

It's not clear what number of blows to the head might lead to the disease, or how widespread the condition is among high-level athletes in high-impact sports. It's likely that genetics plays some role in the development of CTE, as not everyone who sustains brain trauma shows signs of the disease, the Boston University CTE Center has stated.

Originally, CTE was diagnosed only via autopsy. In 2013, researchers at the University of California, Los Angeles, used positron emission tomography (PET) scans to reveal the abnormal buildup of tau in the brains of five living NFL players who were ages 45 to 73. The men had all experienced at least one concussion during their careers, and four had been diagnosed with either mild cognitive impairment or dementia.

While the small pilot study couldn't definitely prove that these former players had CTE, it raises hopes that the condition could one day be identified early, before damage becomes extensive, the researchers said.

Follow Tia Ghose on Twitterand Google+. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Tia is the managing editor and was previously a senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.